MPS Crisis Team Helps Students With Trauma

Group of school psychologists, social workers and counselors respond when student or teacher dies.

Monica Kendrick points to collages made by her fourth-grade students in memory of Sandra Parks. Photo by Allison Dikanovic/NNS.

Stanley Levells recalled feeling worried watching the news one Monday night in November, as a reporter announced that a stray bullet had broken through the window of a house at 13th and Hopkins, killing a 13-year-old girl.

“Every time I hear of something happening in the central city, especially if something happens to a kid, I am always praying that it’s not one of our kids,” said Levells, the eighth-grade teacher at Keefe Avenue School.

The morning after that newscast, he had to tell his students that their classmate, Sandra Parks, had been shot and killed in her home the night before.

“I have a rambunctious group of teenagers in my classroom, and as I looked at them… I could see in each of their faces that a little bit of their innocence was being taken away while that news was being relayed to them,” he said, with a weary heaviness.

When Levells announced Sandra’s death, members of Milwaukee Public Schools’ crisis response team were there with him, and others were dispersed throughout the school as the news was shared with students.

“They were right there with us, and they stood by us,” Levells said.

The MPS crisis response team is a group of school psychologists, social workers and counselors who respond when a student or a teacher dies from any cause, and the school administration asks for support. Team members work full time in different schools and are trained to be a part of the group that responds to a crisis.

“Our job is to stabilize the situation, support the kids who need immediate support, and get things back to a state of being predictable,” said Dena Radtke, MPS manager of school social work and transition services.

The crisis response team has existed more than 20 years, and it is called upon between 20-25 times a year. Radtke leads the team with Travis Pinter, MPS manager of school psychology and allied health services.

The National Association of School Psychology notes that schools play an important role in a community’s ability to heal from a crisis, as they can serve as a safe haven and “as a focus of normalcy in the face of trauma.”

“We recognize that students are not able to learn unless they are in a safe and secure environment,” said Rosario Pesce, school psychology coordinator of clinical training at Loyola University Chicago. “We’re forced to respond when something happens because schools have to get back to some form of functioning while meeting the needs of students.”

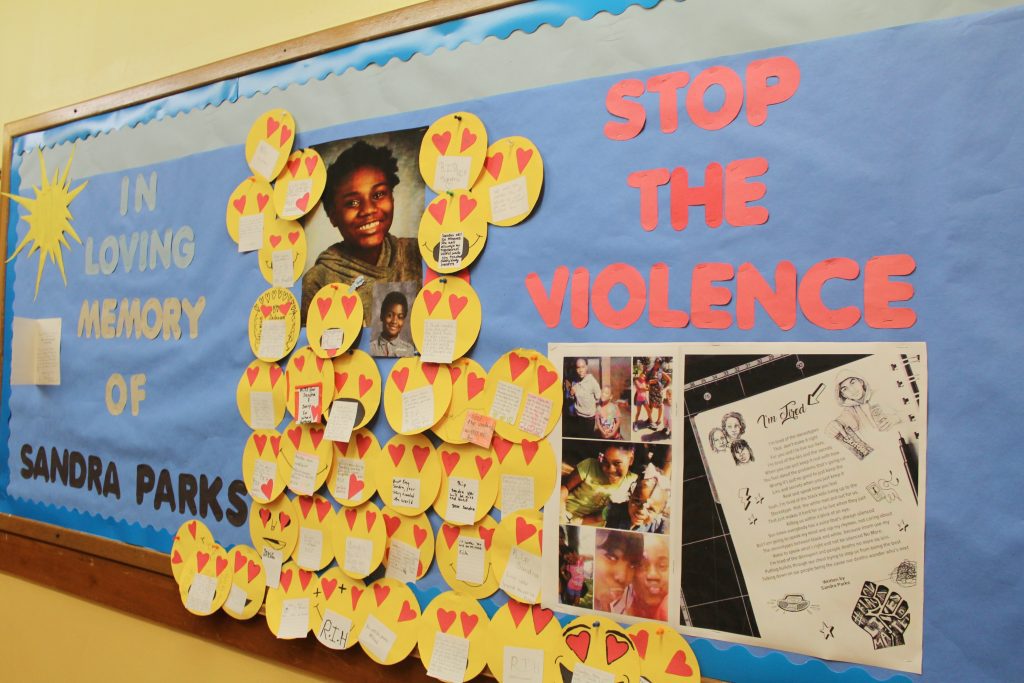

Middle school students at Keefe Avenue School decorated a board in the hallway with emojis to honor their classmate, Sandra Parks. Photo by Allison Dikanovic/NNS.

When the crisis response team members arrived at Keefe that Tuesday morning, they informed staff of Sandra’s death and crafted the message to share with students. Pinter said it’s important for the news to be delivered in a sensitive yet factual way.

Teachers read the same message to every class at the same time, down to the minute.

Monica Kendrick, the fourth-grade teacher at Keefe, was distraught after learning of Sandra’s death. She was very close with Sandra and now teaches her younger brother.

“Here, that day, I couldn’t function,” Kendrick said. “I broke down and couldn’t tell my class what happened. [The crisis team] came in and took over my class. … To have that type of support was amazing.”

Levells said the response among students in his class varied. “A few totally broke down and got pretty hysterical… some were more stoic and calm,” he said.

“For most of the kids, it’s business as usual, and then we pull others out into other spaces where we can work with them without disrupting the environment,” Pinter said. “The majority of the students just kind of want to go about their day.”

Students have the option of leaving class to receive support from the crisis response team. At Keefe, the library was transformed into a counseling center. A box of tissues was on each table.

“In that space is where all the heavy lifting occurs,” Pinter said.

Team members worked with students in groups or individually, helping them process their grief. Pinter said the most important thing is for students to be able to express themselves without further upsetting other students. He said this is difficult because everyone’s response to a death is different, and for older students, the social pressure of peers’ responses can influence their reactions.

Sarah Reuter, an MPS social worker, facilitated the crisis response team at Keefe that day. She said that her role is to make sure students have the support they need. If a student is too overwhelmed, it might be best to go home for the day.

“In other cases, it’s just the initial shock, and they need to talk through that with somebody and feel what that really means, and then they feel like they can go back to class and be with their friends,” Reuter said.

Trauma response

Pinter said that the heart of the crisis team’s work is grief counseling, but when tragic circumstances stir up memories of traumatic events, the team has to work through that first.

More than 60 percent of kids in urban areas nationwide have experienced at least one traumatic event by age 16, according to the National Childhood Traumatic Stress Network.

In 2017, there were 45 children under the age of 18 who were shot and five killed as a result of gun-related homicides in Milwaukee, and in 2018, there have been 50 children shot and four killed, according to the City of Milwaukee Office of Violence Prevention.

Since Sandra was killed as the result of gun violence, hearing the news could set off a trauma response in some kids who may have witnessed violence, Pinter said. The trauma response produces a heightened sense of fight, flight or freeze. “They’re hyper vigilant; their heart rate is accelerated,” he said.

“They could be in the middle of a social studies class, surrounded by their peers, in a very safe environment, but they don’t feel that. They don’t feel safe, which affects how they think… They’re in the back of the brain, worrying about stuff,” Pinter added.

He said that this fear can prevent students from processing sadness, which may cause them to lash out or act defensively.

MPS teachers are trained to address trauma.

“[The training] gave us strategies … to help cope with the stuff the kids are experiencing and struggling with… to understand why they may be acting out,” Kendrick said.

“Sometimes when they’re angry it comes out very nasty to us, the teachers… because they don’t always know how to deal with the emotional stuff that’s going on in their lives,” she said.

In addition to providing trauma training, the district is working to incorporate skills that build resilience in students into its curriculum, to help everyone cope better when incidents occur and to help students better manage their emotions and mental health in general, according to Kimberly Merath, MPS social and emotional learning supervisor.

These kinds of supports become critical after the crisis team leaves, usually after one day.

That Tuesday at Keefe, Reuter and other team members joined the staff meeting after school. They prompted reflection among those gathered and offered resources to connect teachers to counseling services. From that point, the crisis team handed the work off to the school psychologist and social worker at Keefe.

Keefe is also part of School Community Partnership for Mental Health (SCPMH), a collaborative initiative that increases schools’ capacities to provide mental health care to students by partnering with community providers.

Sebastian Family Psychology Practice, LLC, the community provider that offers counseling services at Keefe, estimates that 16,000 students in MPS are in need of some level of mental health intervention.

According to the National Association of School Psychologists, at least one in five children and adolescents nationwide experience a mental health problem during their school years, and 60 percent of students do not receive adequate mental health services.

Kendrick said moving on after Sandra’s death is proving to be difficult for her fourth-grade class.

She said that personally, Sandra’s death continues to weigh on her. “I’m more sensitive, and we’re all more sensitive since we have these strong relationships with our kids,” she said.

Kendrick takes special care to call home to check on Sandra’s brother. She lets him stay after school in her room to finish his math homework or play computer games, and often drives him home after basketball practice. She said as a teacher, she wears “many hats.”

Kendrick and Levells both said that they wish the school and the district could have done more to support their students’ parents and families after Sandra’s death. The crisis response team sent a letter home with students to pass on information about what happened, but Kendrick said she wishes there could have been a meeting.

“I think that could be a family bonding type thing that would help us get through something like this,” she said.

Levells said that he has noticed a change in perspective among some of his students after Sandra died.

“Some have now learned that life can be taken at the drop of a pin, even if you’re not doing anything wrong,” he said. “I think there are some who realized that, and thought ‘we better start doing things that are right… maybe try to do a little bit better and be kinder to each other.’”

This story was originally published by Milwaukee Neighborhood News Service, where you can find other stories reporting on eighteen city neighborhoods in Milwaukee.