All in the Family

“Family Pictures,” a touring show of African American photography, offers depth and humanity, not stereotypes.

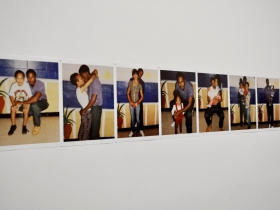

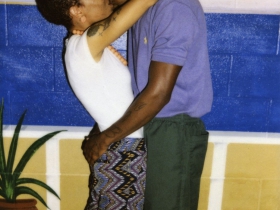

Carrie Mae Weems, from Family Pictures and Stories, 1981-82. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

For many, family encompasses not just blood kin, but those who share a bond — friends, co-workers, and, in some cases, the community as a whole. In the “Family Pictures,” exhibit, now at the Milwaukee Art Museum, 10 African-American artists explore through photography, film and multi-media what the concept of family means to them.

Organized by the Columbus Museum of Art, the exhibit offers viewers a rare and unflinching glimpse into the private lives of African-Americans from the Civil Rights era to the present.

Most of the photos were taken in Harlem, New York and industrial cities like Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Although many are black-and-white silver gelatin prints, color is abundant in many of the works. Lyle Ashton Harris and John Edmonds, both gay artists from New York, use brightly-colored backgrounds and subjects wearing vibrant clothing in their photographs.

Although not part of the original exhibit, photos from Henry Clay Anderson, a member of the 1960s Civil Rights movement, and by Harris line one wall. Anderson focused on black middle-class Americans in the 1960s, an unusual photography theme for the time, says Lisa Sutcliffe, the museum’s Herzfeld Curator of Photography and Media Arts.

DeCarava skillfully used shadows and dark tones to obscure his subjects’ faces. “He concentrated on sweet and quiet daily moments as well as dark tonality, to make you really consider what you are seeing,” says Sutcliffe.

A 1967 Life magazine features a photo spread following the life of a Harlem family, the Fontanelles, taken by Gordon Parks, the magazine’s only African-American photographer. In these photos, particularly “The Fontanelles at the Poverty Board,” Parks masterfully captured the family’s facial expressions. One can almost feel the mother’s despair and the child’s uneasiness at being in a strange, officious place.

Ming Smith’s photos were inspired by the playwright August Wilson (known for plays like Jitney and Fences). Smith was the first African-American woman whose prints were acquired by the Museum of Modern Art in New York. The photos are candid and contemplative: A woman holding a child in her arms sits at a booth in a diner resting her chin in her hand, looking pensive; a pool player focuses intensely on his strategy.

Carrie Mae Weems’ photos chronicle celebration and joyful family moments. In “Family Reunion,” a group of relatives listen respectfully to the family patriarch; “Mom at Work” focuses on an exuberant woman in a department store with arms outstretched. The women clearly loves her job, and her positivity is infectious—the audience wants to smile along with her.

Half of the “Family Pictures” artists showcased are under 40, giving perspectives from a younger generation.

Born in 1989, John Edmonds is the youngest artist featured in the exhibit. His partial use of shadows over his subjects’ faces echo DeCarava’s work, but unlike the influential Harlem photographer, Edmonds works in color. His subjects are mostly close friends with a sense of fashion, from little black dresses to leather biker jackets. To Edmonds, family is chosen, not inherited.

LaToya Ruby Frazier documents her family living in her hometown of Braddock, Pennsylvania amidst the collapse of industry. Despite bleak economic and environmental circumstances, Frazier’s family is portrayed as strong, self-sufficient and close-knit. “Momme” (2008) is a portrait of Frazier’s mother, while the artist herself stands behind her mother and looks directly into the camera. It’s as if both women are two sides of the same person.

In “Aunt Midgie and Grandma Ruby,” (2007) framed photos, a pack of Pall Mall cigarettes, and a comb sit on the family matriarch’s nightstand. Simple everyday things, but to me, this photo of a grandmother’s deeply personal items and mementos was the most moving image in the exhibit.

Although from different generations, artists Lorraine O’Grady (born in 1938) and Deanna Lawson (born in 1979) both experiment with themes of family history and lineage. O’Grady places black-and-white photos of stone sculptures of ancient Egyptian noblewomen and men side-by-side with her male and female relatives to portray the bond between siblings throughout the ages.

Lawson’s 2017 pigment prints, “Soweto Queen” and “Brother and Sister Soweto,” both taken in South Africa, depict subjects who appear protective of their living spaces and proud of their kin. Family photos appear prominently in each print. The works have a nostalgic 1970s quality to them, with muted color tones, that capture a particular generation.

Film and multi-media presentations, including Lyle Ashton Harris’s Ektachrome color reversal slides from the 1980s and 1990s, Kahlil Joseph’s short film “Black Mary,” music by Grace Jones, and a 25-minute film by Sondra Perry, give exhibit visitors an immersive experience. Harris’s slides, some of which contain adult content, showcase his sexuality, close friends, and colleagues in the art world. “Black Mary,” which was commissioned by the Tate Museum in London, follow several Harlem musicians. Singer Alice Smith performs a heartbreaking rendition of Screamin’ Jay Hawkins’s blues tune, “I Put A Spell on You.”

Sondra Perry’s inventive media project, “Lineage for A Multiple Monitor Workstation” Number One, 2015” is a film that follows her family through the process of peeling sweet potatoes in her grandmother’s kitchen. Clad in black with lime-green balaclavas on their heads, a color which matches the background of the screen, the family sings a gospel song. It felt like a humorous take on the “clannish” and insular nature of some families.

“Family Pictures” challenges the notion of traditional family, who should be included and celebrated, and asks its viewers to keep an open mind and do the same.

“Family Pictures,” runs through January 20, 2019, at the Milwaukee Art Museum.

“Family Pictures” Gallery

Art

-

Winning Artists Works on Display

May 30th, 2024 by Annie Raab

May 30th, 2024 by Annie Raab

-

5 Huge Rainbow Arcs Coming To Downtown

Apr 29th, 2024 by Jeramey Jannene

Apr 29th, 2024 by Jeramey Jannene

-

Exhibit Tells Story of Vietnam War Resistors in the Military

Mar 29th, 2024 by Bill Christofferson

Mar 29th, 2024 by Bill Christofferson