When Photography Was Tough Work

Art Museum’s exhibition of nature photos by Muybridge, Watkins and Bennett is a beautiful story.

A century and a half ago, taking the perfect nature photograph involved heavy camera equipment, a discerning eye for detail, painstaking preparation, patience—and luck.

While some of these qualities are still essential when it comes to taking professional photos of any subject, cameras are no longer behemoths made of wood, glass and metal, standing over four feet tall—they are pocket-sized. Many of today’s cell phones have above-average photographic capacities.

“Photographing Nature’s Cathedrals” is a collection of 60 photos from the 19th and 20 century, capturing the Wisconsin Dells and California’s Yosemite Valley and done by artists H.H. Bennett, Carleton E. Watkins and Eadweard Muybridge. Wonderful work that also demonstrates a skillful use of the latest technology at the time—mammoth-plate and stereograph cameras.

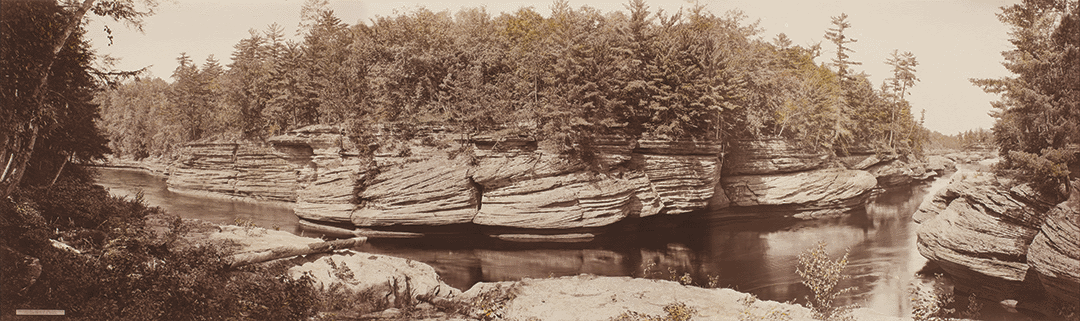

The breathtaking sepia-and-white images—some taken on the edge of a cliff (a precarious feat, given the size and weight of the camera and amount of equipment the photographers traveled with) to get an expansive shot of the valley below–are remarkably detailed.

Viewers can see every tree, every cloud, distant patches of grass. It’s hard to believe the photos weren’t taken using the highest-quality digital camera today. For example, Muybridge’s 1872 photo “Half Dome, Yosemite Valley, California,” taken at 4,750 feet, showcases trees, rocks, and a shadowy, yet vivid, mountain in the background.

The innovative Muybridge also used techniques akin to Photoshop software today. Using multiple glass panes, he seamlessly transposed clouds, rocks, and other images onto existing photos.

Many photos, such as Watkins’ “Bridal Veil Falls in Springtime, Yosemite,” which depict a grassy, treelined area overlooking a stunning waterfall—have a painterly quality.

Indeed, some artists, such as Thomas Hill, whose painting, “Merced River, Yosemite Valley” hangs in the exhibit side-by-side with the photographs, were inspired by nature photographers. Watkins’ photos of Yosemite Valley were so influential that in 1890, Congress designated it as a national park.

Bennett’s stereographic photos, which were taken using a wooden camera with two glass lenses at different angles, created a three-dimensional effect.

Kids and adults will enjoy viewing these photos with a special device.

Many of the natural features Bennett photographed are ideal for 3-D viewing. For example, “Looking out of Boat Cave,” number 150 from the series “In and About the Dells of the Wisconsin River,” treats the cave’s opening as a sort of window to the men canoeing on the vast river on the other side.

According to Pate, many families owned stereographs and stereograph viewers—the predecessor to the View-Master, which was introduced in the late 1930s.

To 21st-century folks, 3-D photos might not seem revolutionary. But in the nineteenth century, before airplanes were invented, stereographs made it possible to travel nationwide within the comfort of one’s living room.

“Stereographs were really the television of the time,” says Ariel Pate, Milwaukee Art Museum Assistant Curator of Photography.

The photographer was also big on panoramic views, says Josh Depenbrok, Public Relations manager for the museum.

Photographs such as 1900’s “The Narrows” were created by piecing three photos together. Images such as these would be placed in train stations to attract visitors to places such as the Wisconsin Dells, Depenbrok noted.

Mid-to-late-nineteenth-century nature photographers were as much explorers, innovators and scientists as they were artists. At a time where much of the American West was largely unexplored territory, Watkins and Muybridge each travelled thousands of miles, using a group of mules to transport their photography equipment and provisions. Although supplies and equipment were sometimes lost or broken, neither photographer suffered any injuries on their photo expeditions.

Nature photos such as these were often used to promote tourism in a post-Civil War era. Railroad expansion made visiting the romanticized American West possible for many Americans.

H.H. Bennett was a former carpenter who, after injuring his hand during his Civil War service, opened his Wisconsin Dells (then Kilbourn City) photography studio in the 1870s. In a time long before social media, Bennett sold many visitors postcards of his nature photos, and souvenir photos. His popularity spread, and before long, the Dells became a major tourist destination for those looking to escape urban life for a weekend.

Wisconsin Dells visitors can still visit the Bennett studio, now a museum.

The “Photographing Nature’s Cathedrals” exhibit goes beyond images. It is a testament to technology and innovation; human creativity and the wondrous beauty of nature.

“Photographing Nature’s Cathedrals”, at the Milwaukee Art Museum, through August 26.

If you think stories like this are important, become a member of Urban Milwaukee and help support real independent journalism. Plus you get some cool added benefits, all detailed here.

Art

-

Winning Artists Works on Display

May 30th, 2024 by Annie Raab

May 30th, 2024 by Annie Raab

-

5 Huge Rainbow Arcs Coming To Downtown

Apr 29th, 2024 by Jeramey Jannene

Apr 29th, 2024 by Jeramey Jannene

-

Exhibit Tells Story of Vietnam War Resistors in the Military

Mar 29th, 2024 by Bill Christofferson

Mar 29th, 2024 by Bill Christofferson

Review

-

Ouzo Café Is Classic Greek Fare

May 23rd, 2024 by Cari Taylor-Carlson

May 23rd, 2024 by Cari Taylor-Carlson

-

‘The Treasurer’ a Darkly Funny Family Play

Apr 29th, 2024 by Dominique Paul Noth

Apr 29th, 2024 by Dominique Paul Noth

-

Anmol Is All About the Spices

Apr 28th, 2024 by Cari Taylor-Carlson

Apr 28th, 2024 by Cari Taylor-Carlson