Hank Aaron Trail Has Historic Murals

Walkers, bikers encounter murals celebrating historic Open Housing Marches of 1967.

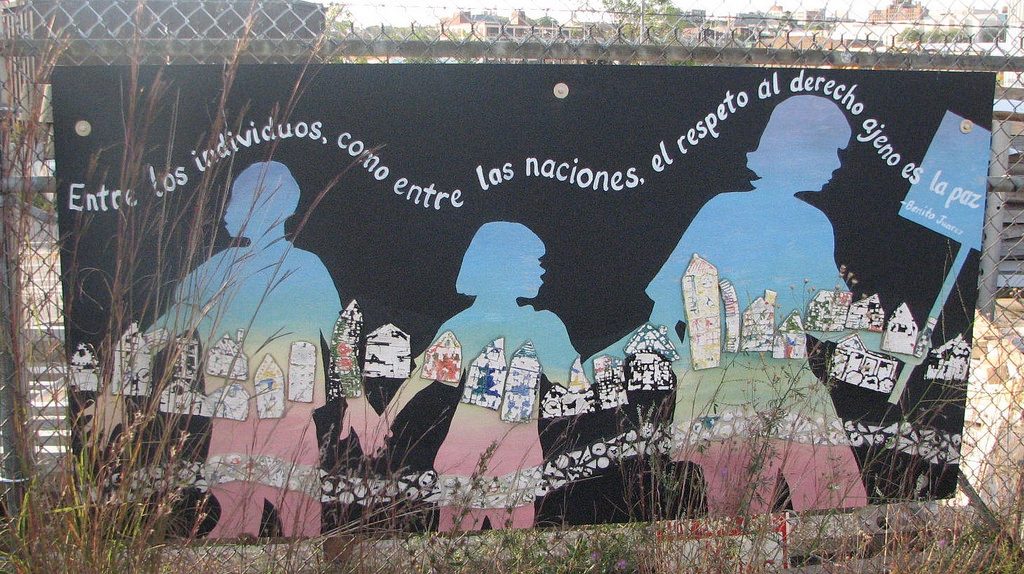

Brightly colored paintings with doves, blue skies and silhouettes of people decorate an ugly, gray chain link fence enclosing an industrial lot. The murals, which feature messages of hope from Chief Joseph, a prominent leader of a Nez Perce tribe, and Mexican hero Benito Juárez contrast with the barbed wire on the fence.

The recent Public Art Walk on the Hank Aaron State Trail gave visitors a chance to learn about the murals and other artwork along the Menomonee River Loop section of the trail, which runs parallel to West Canal Street from North 13th Street to North 25th Street. The event was organized by Menomonee Valley Partners for Valley Week and 200 Nights of Freedom, which celebrates the 50th anniversary of the marches. About 20 people participated.

The vibrant murals were painted by students from 10 different schools near the Menomonee River Valley in 2007, the 40th anniversary of the Milwaukee Open Housing Marches. They created the Civil Rights River Loop Murals along a portion of the Hank Aaron State Trail to commemorate the marches.

The students came up with the designs themselves, said Melissa Cook, who manages the Hank Aaron trail for the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, but they were inspired by a mural created by artist Katrina Motley and students at Milwaukee Institute of Art and Design (MIAD). Motley’s “March On” murals, created in 2006, depict black silhouettes marching against orange and yellow sunsets.

The River Loop is not the most scenic portion of the trail, with bridges and warehouses dominating the Menomonee River Valley, so the art provides a way to engage people, said Cook.

“It’s important we relay that history; you can relay it in a more interesting and engaging fashion through art,” she added.

The trail goes directly underneath the 16th Street Viaduct, also known as the James E. Groppi Unity Bridge. The Menomonee River Valley was known as the Mason-Dixon Line of Milwaukee, separating the predominantly black North Side from the mostly white South Side, Cook explained. The Rev. James E. Groppi, a white Catholic priest, marched with thousands of people, mostly African-Americans, for 200 nights in a row in 1967-1968 demanding open housing and racial equality. A sign directly underneath the bridge explains its history.

“Sometimes it’s best not to forget about our past even with things we’re not proud of,” Cook said, referring to the white counter-protesters’ reaction to the marchers. “It’s the high point and low point in our history all in the same event,” Cook said.

Then-Milwaukee Mayor Henry Maier imposed a voluntary curfew during the marches and called up the National Guard at one point.

“I’m old enough to remember the events discussed,” said Karen Watson, an attendee who grew up in the Milwaukee suburbs. Watson said she remembers the National Guard and a 9 p.m. curfew during the marches.

“I appreciated the art work and I enjoyed learning more about my city,” Watson said.

In addition to the murals, the group saw Katie Martin’s “A Place to Sit,” the gateway sculpture to the River Loop. The three high-back chairs are engraved with the names of Milwaukee Native American nations, including the Oneida Nation, the Sokaogon Chippewa and the Forest County Potawatomi.

Martin was inspired by the writings of local historian John Gurda, who described European settlers playing a game of musical chairs that left Native Americans with nowhere to sit, Cook explained.

“Art on this part of the trail should follow at least the history, culture or environment of the Menomonee River Valley,” said Cook. “We want the art to tell our stories.”

This story was originally published by Milwaukee Neighborhood News Service, where you can find other stories reporting on eighteen city neighborhoods in Milwaukee.