Common Council More Diverse Today, But…

Other cities have done better at embracing diversity.

Vel Phillips (far left) was the only African-American and the only woman in the 1960-1964 Common Council. Photo courtesy of Dustin Weis.

Editor’s note: This article is republished with permission from “Marching On: 50 Years After the Milwaukee Marches,” a project of a journalism capstone class at Marquette University’s Diederich College of Communication.

A few months ago, Ald. Cavalier “Chevy” Johnson voiced his opposition to a proposed law during a robust discussion at a Milwaukee Common Council meeting. The legislators were debating a minimum sentencing requirement that, if passed, would make it easier to send local kids to Lincoln Hills, a juvenile prison 215 miles and 3½ hours away from home.

During the debate, Johnson, a first-term council member who represents District 2, told a story of a young boy who lived in several rough neighborhoods in Milwaukee nearly 25 years ago. That boy shared a twin-sized bed with four other siblings. He soon began hanging out with the wrong crowd, and he stole gummy worms from a corner store “just to prove he was cool,” Johnson said.

“All (he) needed was a good talking to, and for someone to set him straight — so he’d never steal anything again,” Johnson said. “That kid was me.”

The three aldermen who supported the proposed minimum sentencing law represent more economically well-off districts, while the 11 who opposed it represent lower-income areas.

If such legislation existed when Johnson was a child, he might not be where he is today — a member of the most diverse Common Council in Milwaukee’s history.

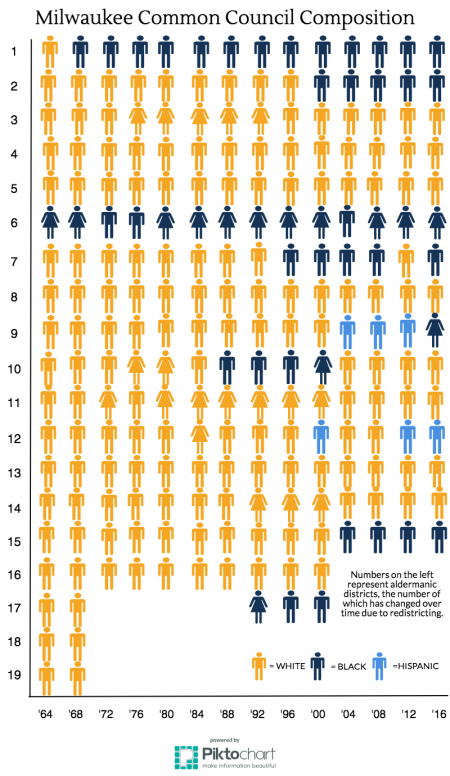

Six members of the council are African-American, two are women and one is Hispanic. Johnson works in the same office once held by Ald. Vel Phillips — the first African-American woman on the council, elected in 1964, just three years before the fair housing marches that helped to transform the city forever.

As the city approaches the 50th anniversary of the marches, local legislators recognize that access for all races to housing wasn’t the only issue marchers cared about. Phillips was a pivotal force in advocating not only for fair housing, but also for political action in the areas of welfare, unemployment and education — issues that many council members still advocate for today.

Diversity on the council has improved since Phillips was the only woman and non-white representative in 1967. But even though the council is more diverse now than it was 50 years ago and some policies have been implemented that reflect this development, the city still hasn’t progressed in ways that the marchers would have envisioned, Johnson said.

“Any time people rise up, voice their grievances, and have the opportunity to move to some other place, or have some other right that was previously denied to them, it’s a good thing,” he said. “At the same time, just because on the policy side things have changed, doesn’t mean the hearts and minds of those in our city, greater community and nation aren’t still hardened.”

Council President Ashanti Hamilton said that while the legislative body is more diverse than ever, the city government still faces very similar challenges to those in 1967.

“We’ve witnessed the problems with having a lack of diversity when you’re trying to push policies that affect a wide variety of people,” Hamilton said. “Inevitably somebody is left out of that process if you don’t have at least enough people who are thinking about it, which is why it’s so important for the community to see themselves represented in their representatives.”

In the past five decades, African-Americans have won 51 out of 219 possible elections, or 23 percent, in a city that is 40 percent black. Hispanics have won just six of 219, or 2.7 percent, yet represent more than 17 percent of the population. Women have won 34 times.

Milwaukee voters have never elected a mayor who was not white or male. Marvin Pratt, an African-American alderman who served the first district for 18 years and as council president for four, was temporarily the city’s chief executive in 2004, after the mayor at the time stepped down. Later that year, Pratt lost his bid for mayor to Tom Barrett, who has held the position since.

A member of the council since 2004, Hamilton is only its fourth non-white president. No woman has held that position, either.

Cities with comparable populations have long done better in terms of diversifying their city leadership. Cleveland had 11 black councilmen in 1967. Frank Jackson, an African-American, has served as that city’s mayor since 2005. Columbus, Ohio, elected its first black mayor in 1999, and Raleigh, North Carolina, did so in 1973.

What does this lack of diversity mean for the Milwaukee council’s ability to enact change? Hamilton, who represents District 1, said that while there’s been a movement away from overt racism in the last 50 years, both in politics and society at large, institutional racism still exists in lawmaking. He cited the city’s “failing school system,” the disparities in sentencing for crack cocaine, lack of economic opportunities for minorities and scarcity of low-income housing.

“It would be very difficult for folks to have a school system in any major metropolitan area, although there are some that are doing OK, that would be failing the way that these are failing if the kids that were in the school were more valued,” Hamilton said.

District 13 Ald. Terry Witkowski, an alderman for 16 years who worked for the city since 1968, said that every council member has long wanted a united city. Yet Witkowski attributes that responsibility more to the electorate than to those who are elected.

While Witkowski was one of the three aldermen who voted for the mandatory sentencing amendment, he agreed that institutional racism still exists in policy making. But he disagreed that it’s one of the causes of a failing school system. Rather, he said, the lack of parental involvement is the root cause of achievement differences for minority students.

Hamilton pointed to a specific policy he said speaks to the potential of a diverse council. In 2009, it passed the Milwaukee Opportunities Restoring Employment (M.O.R.E.) legislation, which increased the percentage of residents required to work on city development projects from 25 to 40 percent — including those from disadvantaged communities and who are unemployed or underemployed.

Johnson cited another law that ensured that those who live in the city have the same opportunity as non-city applicants to work for the police department, one of the largest and most powerful in the local government. “If we’re going to have an open and honest and true city, then our departments and the people who make the city go every day should reflect that, too,” he noted.

Witkowski is also optimistic about the current council. Even though increased diversity often leads to increased disagreement, it’s healthy for the city, he said.

“If we were a group of 15 guys, we would focus on guy things,” he said. “If we were all Hispanic, African-American, white, it would all be the same. We’re going to come to the table with our own viewpoint. Period. But that helps give us direction. And the overall attitude is such that we should be working on behalf of the whole. That’s the purpose of government.”

This story was originally published by Milwaukee Neighborhood News Service, where you can find other stories reporting on eighteen city neighborhoods in Milwaukee.

Political Contributions Tracker

Displaying political contributions between people mentioned in this story. Learn more.

- September 17, 2019 - Cavalier Johnson received $200 from Terry Witkowski

- October 10, 2017 - Ashanti Hamilton received $100 from Marvin Pratt

- February 8, 2016 - Ashanti Hamilton received $200 from Marvin Pratt

- October 8, 2015 - Cavalier Johnson received $50 from Terry Witkowski

50 Years After The Marches

-

Pandemic Shines Spotlight on Workers’ Struggle

Sep 7th, 2020 by Erik Gunn

Sep 7th, 2020 by Erik Gunn

-

UW System Expects $212 million in Losses

![Van Hise Hall in the background. Photo by James Steakley (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) or GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://urbanmilwaukee.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/1017px-Ingraham_Van_Hise_carillon-185x122.jpg) May 8th, 2020 by Rich Kremer

May 8th, 2020 by Rich Kremer

-

51 of 72 Counties Now Back Fair Maps

Apr 15th, 2020 by Matt Rothschild

Apr 15th, 2020 by Matt Rothschild