Will Supremes Rule on State Redistricting?

Past cases show Supreme Court is reluctant to overrule district courts.

The U.S. Supreme Court has made a complete hash of its political gerrymandering cases. Consider the nearly unintelligible opening paragraph of its 2006 decision in League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC) v. Perry:

JUSTICE KENNEDY announced the judgment of the Court and delivered the opinion of the Court with respect to Parts II–A and III, an opinion with respect to Parts I and IV, in which THE CHIEF JUSTICE [Roberts] and JUSTICE ALITO join, an opinion with respect to Parts II–B and II–C, and an opinion with respect to Part II–D, in which JUSTICE Roberts SOUTER and JUSTICE GINSBURG join.

In addition to Justice Anthony Kennedy’s opinion, which was partly also the opinion of the court—and partly not—his colleagues managed to produce a total of five separate opinions which both agreed and disagreed with Kennedy. Good luck to lower court judges and lawyers trying to pick through the wreckage to try to decide which parts the court actually decided and which were just arguments among justices.

The conventional wisdom is that Justice Kennedy will decide whether Wisconsin’s gerrymander lives or dies. This reflects the widespread assumption that the rest of the court is evenly split between four justices who hate gerrymanders and will vote to kill Wisconsin’s version (generally called the “liberals”) and four who are generally fine with gerrymanders, or at least unfine with court interference with them (generally called the “conservatives”).

Kennedy breaks from his fellow conservative in his discomfort with gerrymanders. Here is how he described them in his 2004 Vieth v. Jubelirer concurrence:

Here, one has the sense that legislative restraint was abandoned. That should not be thought to serve the interests of our political order. Nor should it be thought to serve our interest in demonstrating to the world how democracy works. Whether spoken with concern or pride, it is unfortunate that our legislators have reached the point of declaring that, when it comes to apportionment, “We are in the business of rigging elections.”

Despite his discomfort, however, Kennedy has yet to vote against a partisan gerrymander. In each of the cases decided he rejected the proposed standards and voted to allow the gerrymander.

In Vieth, Justice Antonin Scalia seized on this history to argue that it means that the search for standards must be abandoned:

… no judicially discernible and manageable standards for adjudicating political gerrymandering claims have emerged. Lacking them, we must conclude that political gerrymandering claims are nonjusticiable … Eighteen years of essentially pointless litigation have persuaded us that Bandemer [a 1986 decision] is incapable of principled application. We would therefore overrule that case, and decline to adjudicate these political gerrymandering claims.

Will Justice Kennedy vote to uphold the district court’s decision rejecting the Wisconsin gerrymander? Two recent events suggest reasons for caution:

First, his was one of five votes for a stay on the district court’s order that the Wisconsin legislature come up with new districts.

In addition, earlier this year, the court rejected North Carolina’s gerrymander in Cooper v. Harris, concluding that it was race based. Kennedy, along with Chief Justice John Roberts, signed onto a dissent written by Justice Samuel Alito. It included the following warning about challenges to politically motivated gerrymanders:

There is a final, often-unstated danger where race and politics correlate: that the federal courts will be transformed into weapons of political warfare. Unless courts “exercise extraordinary caution” in distinguishing racebased redistricting from politics-based redistricting, … they will invite the losers in the redistricting process to seek to obtain in court what they could not achieve in the political arena. If the majority party draws districts to favor itself, the minority party can deny the majority its political victory by prevailing on a racial gerrymandering claim. Even if the minority party loses in court, it can exact a heavy price by using the judicial process to engage in political trench warfare for years on end.

In his briefs defending the Wisconsin gerrymander, Wisconsin Attorney General Brad Schimel argues that the Vieth decision means that the partisan gerrymanders are “nonjusticiable.” This is misleading. Support for this position never exceeded four justices, so it never represented the opinion of the court. Moreover, only one of the justices signing onto the Scalia argument remains (Clarence Thomas). In his LULAC concurrence/dissent, Roberts (joined by Alito) is careful not to take a position on this question:

I agree with the determination that appellants have not provided “a reliable standard for identifying unconstitutional political gerrymanders.” … The question whether any such standard exists—that is, whether a challenge to a political gerrymander presents a justiciable case or controversy—has not been argued in these cases. I therefore take no position on that question, which has divided the Court, see Vieth …

I would argue that factual evidence should infuse decision-making, and from that perspective, reading Supreme Court decisions can be disturbing. There is a certain intellectual arrogance in believing that because the court has not found a standard that meets its expectations, no such standards can ever be found. Too often assertions are made without bothering to discover whether the evidence backs them up.

Why has the Supreme Court been so unable to effectively grapple with gerrymandering for political advantage? Compared to many other questions that courts considered (whether a shooting is self-defense, for instance), the issues seem relatively simple: were those in charge motivated to favor one party over another, is the result seriously asymmetric, and would other plans serve the same legitimate goals while being less biased?

One factor, I think, is that the justices suffer from a serious misunderstanding of the power of modern American partisanship. Consider the following assertion from Justice Scalia’s Vieth decision:

Moreover, to think that majority status in statewide races establishes majority status for district contests, one would have to believe that the only factor determining voting behavior at all levels is political affiliation. That is assuredly not true.

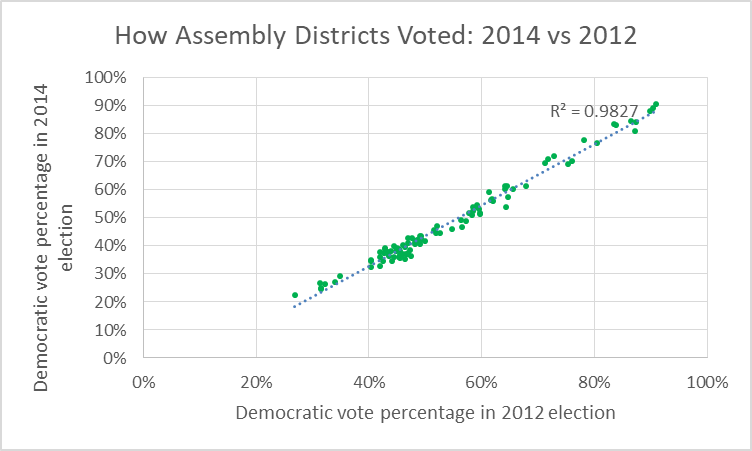

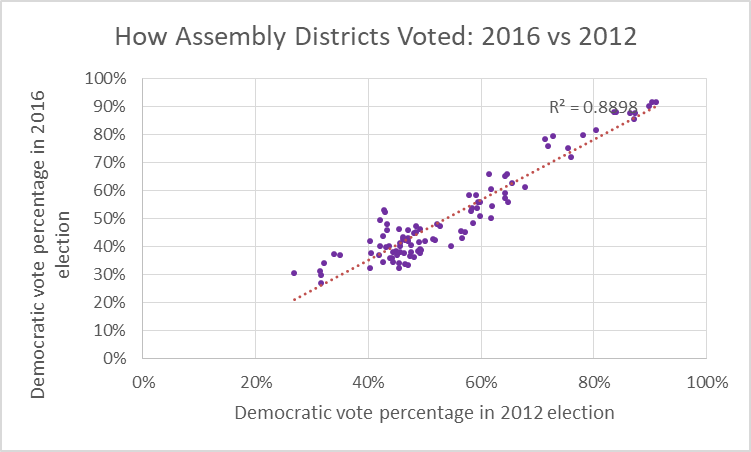

Now compare the vote by Assembly district for president in 2012 and that for governor in 2014. Political affiliation, if not the only factor, is by far the most important factor determining voting behavior. The following chart compares each district’s per cent Democratic vote in 2012 with its vote in 2014.

Even the 2016 presidential votes follows this pattern. Despite all the former Obama voters who switched to Trump and the suburban Republicans turned off by Trump’s thuggery, the 2012 results do an overwhelming job of predicting district votes in 2016. The correlation falls only from .99 to .94.

While political affiliation is not the only factor determining voting behavior at all levels, it comes very, very close.

A second theme that runs through the opinions is a belief in the need for a single formula for measuring partisan bias, one that can be universally applied. In truth, there are a variety of tests for gerrymandering. Rather than a weakness the variety is a strength. They can be used to check each other. If, for some reason, one doesn’t fit others are available.

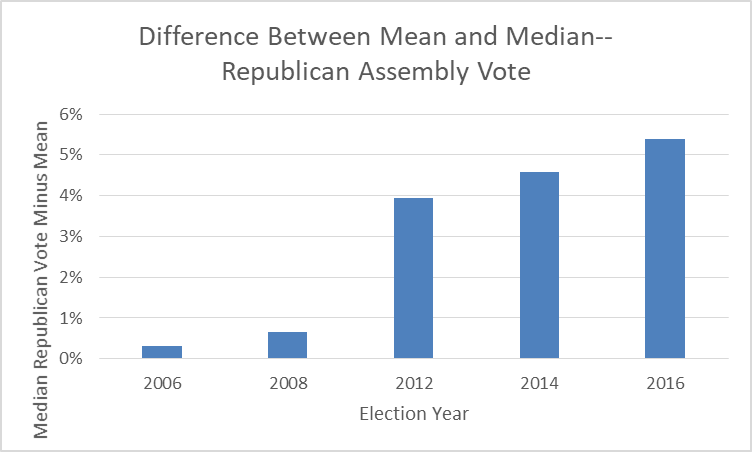

If a distribution is symmetric, the mean and median will be approximately the same. The aim of gerrymandering, of course, is to make the distribution of districts asymmetric to favor one party over the other.

The way to do this is to “pack” many of the other party’s voters in a few districts while spreading the remainder over a large number of districts where they will be safely in the minority.

The following graph shows the median minus the mean of the Republican assembly vote before and after Republicans redistricted the assembly in 2010. As the graph shows, the median-mean difference took a large jump following the gerrymander, reflecting its use of cracking and packing.

A third theme is a seeming reluctance by the Supreme Court to trust the district courts to make intelligent decisions about partisan gerrymandering. In the Cooper decision, for instance, rather than substitute their opinion for that of the district court, the Supreme Court majority limited themselves to determining whether the lower court’s decision made a clear error. This approach even earned the endorsement of Justice Thomas who wrote: “I write briefly … to note my agreement, in particular, with the Court’s clear-error analysis.”

Rather than try to come up with a formula that it can hand down to the district court, the Supreme Court could allow the district courts to determine on a case-by-case basis whether a redistricting plan was aimed at gaining partisan advantage, whether it succeeded in doing so, whether the advantage was durable, and whether the plan was the result of legitimate policy goals.

Data Wonk

-

Life Expectancy in Wisconsin vs. Other States

Dec 10th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Dec 10th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

-

How Republicans Opened the Door To Redistricting

Nov 26th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Nov 26th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

-

The Connection Between Life Expectancy, Poverty and Partisanship

Nov 21st, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Nov 21st, 2025 by Bruce Thompson