28 Years in Solitary Confinement

One Waupun inmate’s incredible story. He is suing the state.

LaRon McKinley spent nearly three decades in solitary confinement. He rejects the diagnosis that he is delusional. But in a phone interview he acknowledged that spending about 28 years in solitary damaged him psychologically. This artist’s illustration was based on surveys conducted by the Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism with Wisconsin prisoners in administrative solitary confinement. Painting by Emily Shullaw for the Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism.

LaRon McKinley spent nearly three decades in solitary confinement.

After a months-long hunger strike in 2016, McKinley was moved in October from Waupun Correctional Institution to the Wisconsin Resource Center, a facility run by the state Department of Health Services for inmates with mental illnesses.

Now 61, McKinley rejects the diagnosis that he is delusional. But in a phone interview — allowed under DHS rules — he acknowledged that spending about 28 years in solitary damaged him psychologically.

McKinley was placed in administrative confinement — a form of solitary with no set end date — after two violent incidents in the late 1980s.

One was a physical altercation with a fellow inmate. The second was an escape in which McKinley shot a sheriff’s deputy and a second deputy was injured when he jumped from the vehicle used to transport McKinley. The gun came from a female jailer, who was later prosecuted for her part in the escape.

McKinley has committed other acts that have kept him in solitary. Over the years, he has received 17 conduct reports for battery or assault, most recently in 2013, when he threw feces on a correctional officer, according to the DOC.

McKinley is suing the state Department of Corrections in federal court, arguing that the “continued isolation impairs his capacity to process information and function normally, which puts him in a Catch-22 of indefinite isolation that they know he is unable to extract himself from.”

In a response to his lawsuit, the DOC denies some of McKinley’s alleged conditions in confinement, including the constant screaming and banging, extreme high or low temperatures and abuses by security staff.

McKinley spoke to the Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism’s managing editor, Dee J. Hall, by telephone from the Wisconsin Resource Center. Here is part of the transcript of that conversation.

Q: Are you the longest person serving in this status in the state of Wisconsin, as far as you know?

A: Yes, to my knowledge.

Q: Can you tell people what daily life is like in that status?

A: In the DOC, you spend 23 or more hours a day in a cell alone in an environment that has little meaningful stimulation, you know, mental or physical isolation from not only from your family and whatnot but even the people around you, other prisoners. It’s an environment where, you know, you experience a real deep loneliness and isolation from people — your own social group, society, your family, and it’s an environment that is psychologically dangerous, you know, from my experience.

Q: How did you end up at the Wisconsin Resource Center?

A: In the course of that hunger strike, which lasted about 82 days and I believe I was force-fed about 67 of those days, the DOC, through the warden and deputy warden there at Waupun, approached me with an offer to send me here and to engage in programming that, if completed, then …. I would be able to work my way out of administrative confinement and I would be sent to another DOC system, because the DOC officials agreed that I would be set up for failure if placed in the DOC system in Wisconsin. Because they seem not to be able to let go of my past.

Q: Tell me a little bit about your past and how you ended up in administrative confinement.

A: In 1988, October 24th of 1988, I was in the general population of Waupun, working in the prison industries … and told to train another prisoner, which I started doing. … He attacked me with weapons and these were tools we were working with … He got injured real bad and I ended up with no — not even a scratch on me. But he ended up with multiple and pretty serious injuries and so they charged me with battery. … and from that point they placed me in administrative confinement, and it was a slippery slope from then on.

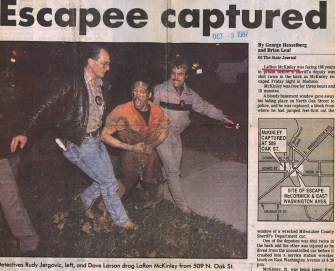

LaRon McKinley was placed in administrative confinement after his 1987 escape in Madison, Wis. in which he shot a Milwaukee County Sheriff’s deputy. Another deputy was injured while leaping from the squad car in which the three were riding. Photo courtesy of the Wisconsin State Journal.

Q: There was an incident in which you attempted to escape and some deputies were injured. Do you want to tell me about that?

A: I befriended a female deputy sheriff and she helped me escape by bringing me a weapon into the jail, and deputies were hurt doing a transport from Milwaukee to Madison, and I escaped for a short period of time and I was recaptured — maybe a matter of several hours. And this crime is one of the crimes that I was also placed in administrative confinement (for). … Police or criminal justice officials are a fraternity, so if you do something to one somewhere, then you know these officials everywhere have a problem with you … They have a long memory of that.

Q: The Wisconsin Resource Center is a place for inmates that have mental illness. Can you tell me what your diagnosis is?

A: They diagnosed me, I was diagnosed with delusional disorder, but this is something that I deny. … They induced these symptoms through these coercive psychological techniques that they engaged in just to pay me back for my crime in Milwaukee with the deputy sheriffs and other conduct that I engaged in, you know, assault against DOC officials over 25 years ago. This was a retaliatory thing that they engaged in against me and it induced these symptoms. So, I’m fine. I refute, I deny that I have any type of mental illness.

Q: What is your ability right now to deal with people? You’ve been largely shielded from normal human interaction for quite a long time.

A: After being isolated for so long you become distrustful of people and you feel uncomfortable in large groups and you have to readjust to just being in proximity of other people and interacting with them and whatnot. Even now, I’m very sensitive to stimuli. I have hypersensitivity to noise and sound. Strong startle reaction. So, I’m still wrestling and struggling with the effects of long-term isolation, but the staff here are very skilled and they’ve given me a chance to demonstrate that I can work myself through this.

Q: What was the goal of your hunger strike and do you feel like maybe you’re accomplishing some of those goals right now?

A: I believe that some of my own personal goals in terms of to get myself out of the mental and physical abuse that I was being subjected to and the lack of opportunity to show that I could progress out of administrative confinement … I believe I accomplished that. But we still have a lot of work for the individuals who are being held in long-term solitary confinement now … So we still need to have a cap, a limitation, placed on that type of confinement.

Q: Anything else you’d like to say?

A: I would like to say that there needs to be emphasis, re-emphasis, placed on the concept of rehabilitation … to deal with high management and difficult-to-manage prisoners and administrative confinement prisoners to stop them or prevent and help them from being held in long-term isolation. Because it’s a psychologically dangerous form of confinement. It’s harmful to humans. And there needs to be something done about it. Legislatively or otherwise, negotiation — by any means necessary.

The Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism’s reporting on criminal justice issues is supported by a grant from Vital Projects at Proteus. The nonprofit Center (www.WisconsinWatch.org) collaborates with Wisconsin Public Radio, Wisconsin Public Television, other news media and the UW-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by the Center do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.

Cruel and Unusual

-

Jail Fees Can Leave Inmates in Debt

Oct 4th, 2019 by Izabela Zaluska

Oct 4th, 2019 by Izabela Zaluska

-

Rules Violations Cause 40% of Prison Admissions

Jul 3rd, 2019 by Izabela Zaluska

Jul 3rd, 2019 by Izabela Zaluska

-

Evers Faces Hurdles to Cutting Prisons

Jul 1st, 2019 by Izabela Zaluska

Jul 1st, 2019 by Izabela Zaluska