Wisconsin Curbs Solitary Confinement

State joins national reform movement, but prisoner advocates say more could be done.

Attendees at a rally against solitary confinement spend time inside a mock solitary confinement cell outside the state Capitol in Madison in October. The cell, built by the statewide group Wisdom, is based in part on drawings made by former inmate Talib Akbar during one nearly yearlong stint in isolation. Photo by M.P. King of the Wisconsin State Journal.

Wisconsin has made a “culture shift” in its use of solitary confinement in prisons, eliminating it as punishment for minor rule infractions and cutting the time inmates spend in isolation for more serious offenses, Department of Corrections officials say.

In most cases, the state prison system will no longer discipline inmates for self-harm or suicide attempts by sentencing them to time in solitary confinement. And mitigating factors such as mental illness will be considered in meting out punishment, two top DOC officials said in an interview granted as part of a legal settlement with the Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism.

The changes in so-called restrictive status housing at DOC come as powerful voices ranging from Democratic President Barack Obama to conservative billionaire Charles Koch are calling for less incarceration and more rehabilitation. Republican Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker has, for most of his political career, gone in the opposite direction. As a lawmaker, he spearheaded passage of the “truth-in-sentencing” law enacted in 1999 that vastly increased the length of sentences for Wisconsin prisoners.

In 2011, his first year as governor, Walker signed a bill that he had championed ending the early-release program launched under Democratic Gov. Jim Doyle. Walker has refused all pardon requests. Since he took office, releases granted by the Walker-appointed Parole Commission have nearly ground to a halt, a 2014 Wisconsin State Journal investigation found.

But on this topic — reducing the use of solitary confinement — Walker told the Center in December that he was supportive of Corrections Secretary Edward Wall’s push to rethink its use in Wisconsin prisons. His spokeswoman declined this month to say whether Walker approves of the new policies.

Major policy shift

So-called restrictive status housing cells at Waupun Correctional Institution are just over 6 feet wide. Some Wisconsin prisoners have spent months or years in isolation as punishment for violating prison rules. New policies enacted by the state Department of Corrections have already reduced the number of inmates and length of time spent in isolation. Photo from the Wisconsin Department of Corrections.

Solitary confinement in Wisconsin involves placing inmates in small concrete cells with little natural light and minimal human contact for nearly 24 hours a day. Food is passed through a slot in a solid door.

Prisoners are generally allowed few possessions in solitary confinement. In some instances, inmates can be left for hours or days with no bedding, except for a mattress, or clothes, except perhaps a paper gown. Any movement outside of the cell is done in shackles. Inmates also can be strip searched.

Dr. Kevin Kallas, DOC’s director of mental health, told the Center the agency intends to “change our attitudes and our culture about restrictive housing, how we use it and who we use it for.”

“We want to make the experience to be as constructive, instructive, rehabilitative as possible, and obviously that’s a work in progress,” Kallas said. “We have a ways to go with that. But that’s our clear direction.”

In addition, correctional officers are now being rotated through restrictive housing units after 14 weeks to reduce staff burnout, said Cathy Jess, administrator of the Division of Adult Institutions.

Advocates said the move could lead to fewer allegations of abuse such as those documented last year by a Center investigation of Waupun Correctional Institution’s solitary confinement unit.

That investigation found 40 alleged incidents of serious physical or psychological abuse of inmates by staff in the solitary confinement unit, formerly known as the segregation unit, two-thirds of them tied to a single guard, Joseph Beahm. Beahm remains at the prison and continues to work in the unit; officials have said prisoners complaining of abuse were lying.

The Rev. Jerry Hancock of Wisdom, the faith-based group that has been pushing to end solitary confinement in Wisconsin prisons, said the organization’s three-year campaign — and years of legal challenges by state prisoners — appear to be paying off.

Kallas said under the old policy, a prisoner could be isolated for up to 360 days for many offenses. They included such infractions as assault, lying about employees and possession of tobacco. The new policy states that restrictive housing is to be used only for offenses that “create a serious threat to life, property, staff, or other inmates, or to the security or orderly operation of the institution.”

The new rules set a maximum initial term of 90 days for the most serious offenses, including aggravated assault on staff or hostage-taking. The sentence can be adjusted downward for mitigating factors, such as mental illness, or upward for aggravating factors, such as whether an inmate is a serial violator. All sentences of 120 days or more must be reviewed by the DOC secretary.

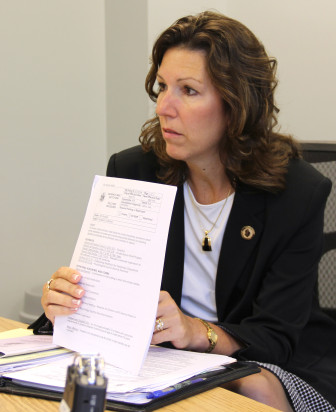

Cathy Jess, administrator of the Department of Corrections’ Division of Adult Institutions, and Dr. Kevin Kallas, mental health director for the DOC, discuss major changes made to the agency’s use of “restrictive status housing” or solitary confinement. Jess said the policy marks a “culture shift” by the department. Photo by Abigail Becker of the Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism.

“As a department … we have continued to make changes and we will continue to make changes,” Jess said. “It is somewhat of, I would say, a culture shift for staff. I’ve been in the department for 29 years. Things change, the pendulum swings with corrections, and depending on the public’s opinion and how laws get passed and different things.”

The Rev. Kate Edwards, an ordained Buddhist chaplain who volunteers in the state prisons and leads Wisdom’s anti-solitary effort, said the changes, if implemented as written, would be “huge.” But she is concerned about the lack of a specified maximum period of confinement for rule violations involving “aggravating” circumstances.

Under the new policy, correctional officers also are now encouraged to work with inmates to devise mutually agreeable disciplinary sanctions for minor offenses, Jess said.

And in a major policy shift, Kallas said inmates will no longer be punished just for harming themselves, unless they are “disruptive or disrespectful or assaultive.”

“So if an inmate is cutting themselves, for example, they should not get a conduct report for disfigurement, for example. Or if they take an overdose, they should not get a conduct report for misuse of medication,” Kallas said. “We want to take the approach of treating for that behavior rather than disciplining for that behavior.”

Asked if the changes had resulted in more security problems in the prisons, Jess said it has been the opposite.

“We are not hearing there is any more disruption than before these policies were put in place,” Jess said. “We are hearing there are less disciplinary reports.”

More changes may be on the way.

According to documents obtained by the Center under an open records request and settlement, DOC is considering changes to a policy that allows prison officials to keep inmates in solitary confinement indefinitely until their behavior improves. A federal appeals court found in 2014 that conditions endured by a mentally ill Green Bay Correctional Institution inmate while under such a plan may have violated the U.S. Constitution’s ban on cruel and unusual punishment.

Cathy Jess, administrator of the Wisconsin Department of Corrections’ Division of Adult Institutions, holds a copy of the agency’s new policy that calls for less time in isolation for inmates who break prison rules. The Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism filed a lawsuit earlier this year to gain access to records about the new policy. Photo by Abigail Becker of the Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism.

“I’m very grateful to see that they have made this much progress, but I feel that we still have a pretty long way to go,” Edwards said. “Also, there is a very deep conviction in me that any amount of torture is not acceptable on any count, and I consider isolated confinement — no matter what they call it — to be torture.”

Edwards noted some infractions that in the past landed prisoners in solitary confinement for months may now, under the new policies, be handled with little to no time in isolation.

DOC tightlipped on changes

Earlier this year, DOC officials failed to release records related to the policy changes under discussion, prompting the Center to file a lawsuit against the agency in January. Under a settlement reached in June, the department turned over the records, made Jess and Kallas available to explain the changes and paid the $4,500 legal bill for the Center’s attorney, Christa Westerberg of McGillivray, Westerberg & Bender in Madison.

The new policies, which officially took effect June 1, seek to more closely match the nature and severity of an offender’s conduct with the punishment, Kallas said. For example, minor prisoner misbehavior may be handled by loss of privileges, confinement to a regular cell or loss of recreation rather than solitary confinement.

“We have found just in the last year or so since we’ve started to implement some of these changes that our overall numbers in restrictive housing have gone down and that we’re using more of these alternative dispositions, rather than restrictive housing,” Kallas said.

“That, I think, is a really important piece of this. Because the issues and the problems that we run into with restrictive housing all become easier to manage and easier to solve if we have fewer people in restrictive housing.”

But Hancock, a former prosecutor who heads the Prison Ministry Project at Madison’s First Congregational United Church of Christ, questioned the DOC’s claim that the number of prisoners in restrictive housing has shrunk. He said corrections officials have repeatedly told Wisdom they do not keep such statistics.

“I don’t know where they’re getting their numbers,” he said.

The Rev. Jerry Hancock of First Congregational United Church of Christ in Madison tells a crowd at the state Capitol in October that solitary confinement is torturous, costly and ineffective. The rally was organized by Wisdom, a faith-based group that has been pushing to eliminate solitary confinement. Wisconsin is one of 10 states that is cutting back on use of isolation to punish prisoners. Photo by M.P. King of the Wisconsin State Journal.

In a survey released in 2013, the Association of State Correctional Administrators reported that between Dec. 1, 2011 and Dec. 1, 2012, there were 4,327 male prisoners in Wisconsin — or roughly 20 percent of the total inmate population — placed in solitary confinement at some point that year. The survey found 14 inmates had spent more than 10 years in isolation.

Jess said DOC has begun tracking how many prisoners are in restrictive housing at any one time but still does not keep statistics on the length of time inmates spend there.

Article Continues - Pages: 1 2

Cruel and Unusual

-

Jail Fees Can Leave Inmates in Debt

Oct 4th, 2019 by Izabela Zaluska

Oct 4th, 2019 by Izabela Zaluska

-

Rules Violations Cause 40% of Prison Admissions

Jul 3rd, 2019 by Izabela Zaluska

Jul 3rd, 2019 by Izabela Zaluska

-

Evers Faces Hurdles to Cutting Prisons

Jul 1st, 2019 by Izabela Zaluska

Jul 1st, 2019 by Izabela Zaluska

How about spending money on kids reading and fixing neighborhoods, stopping crime instead of trolleys and arenas.