The Cult of the Free Market

Adam Smith gets distorted as partisan ideologues increasingly skew data to simplify reality.

Recently the New York Times published an essay by its long-time international correspondent John Burns titled The Things I Carried Back. Burns concludes that what his experience taught him, “more than anything else, was an abiding revulsion for ideology, in all its guises.”

From Soviet Russia to Mao’s China, from the Afghanistan ruled by the Taliban to the repression of apartheid-era South Africa, I learned that there is no limit to the lunacy, malice and suffering that can plague any society with a ruling ideology, and no perfidy that cannot be justified by manipulating the precepts of a Mao or a Marx, a Prophet Muhammad or a Kim Il-sung.

Burns’ final paragraph turns to thoughts of home:

My catalog of such moments in the grim dictatorships of the world could fill a book, or three. But coming home to the countries of the West, where nobody dies for a moment’s lapse in fealty to a prime minister or a president, it can be depressing beyond words to hear the loyalists of a given political creed — whether of the left or the right — adopt the unyielding certainties common in totalitarian states. Our rights to think and speak freely have been won at great cost, and we abuse them at our peril.

At one level I share Burns’ puzzlement as to why so many Americans voluntarily outsource their thinking to those more interested in preaching a doctrine than understanding how the world works. As Burns notes, the punishment for heretical thinking is much milder in the West than in other parts of the globe.

We are also a society that values thinking for oneself, at least in our rhetoric. Pollsters have found that in the last few years the proportion of voters describing themselves as “independents” has steadily risen. Yet it appears that true independents are increasingly rare; voters just like the sound of the word. Partisanship has gripped the land, and particularly this state.

Such ideology brings advantages to the person who subscribes to it. It removes uncertainty. If we limit our reading, radio, or television programs to those that share our ideology, we enjoy the pleasure of being right, of having our views confirmed as correct. I think this is what Justice Antonin Scalia had in mind when he told an interviewer he’d given up reading the Washington Post and the New York Times in favor of the Wall Street Journal and the Washington Examiner, publications that share his view of the world.

Ideologies also make it easy to separate heroes from the villains. And most important, ideologies supply answers to life’s most complicated and perplexing questions. Do you want to create 250,000 new jobs in Wisconsin in four years? Just cut taxes and government spending, hang out a sign that Wisconsin is open for business and the jobs will appear. Concerned that too many MPS kids don’t gain the skills they need? End the charter and voucher programs, end testing, use the money saved to double school budgets and the problem will be solved.

Data used wisely can correct ideology. It can directly contradict claims being made either by the ideologues themselves or by politicians hoping to win the ideologues’ favor, or at the very least, data can add depth and nuance to these claims. At the most, it can point to solutions not even being discussed.

The ideological use of data starts with a solution—for instance, a right to work law—and then searches out evidence to support that solution. The evidence is carefully cherry picked so anything that contradicts the preferred result is rejected. The usual cautions, notably against assuming that a correlation proves causation, are ignored.

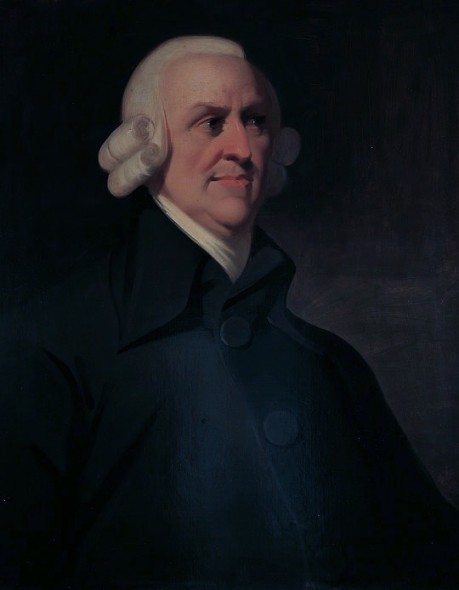

Today’s most prominent ideology, at least in America in the economic sphere, is the cult of the free market that claims roots with Adam Smith’s An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations published in 1776. Smith is an unlikely choice as a cult founder: he was far from “a Mao or a Marx, a Prophet Muhammad or a Kim Il-sung.” Rather than an ideologue, he was one of the most prominent members of the Scottish Renaissance who prided themselves on challenging old verities. He was clear-eyed when it came to business:

People of the same trade seldom meet together, even for merriment and diversion, but the conversation ends in a conspiracy against the public, or in some contrivance to raise prices.

No fawning talk of “job creators” came from Smith. One can imagine his bemusement at the Wisconsin legislature’s decision to turn over the writing of its mining laws to a mining company:

The interest of [businessmen] is always in some respects different from, and even opposite to, that of the public … The proposal of any new law or regulation of commerce which comes from this order … ought never to be adopted, till after having been long and carefully examined … with the most suspicious attention. It comes from an order of men … who have generally an interest to deceive and even oppress the public.

One can imagine the reception Smith would receive from, for instance, the Wisconsin Manufacturers and Commerce.

The cult of the free market should not be confused with the market economy model that has proven very useful in the two centuries since Smith kicked it off. The model can be used to help our understanding; the cult constrains it.

This raises two mysteries about the filtering of data to reach a predetermined conclusion. Why doesn’t the reader realize he or she is being spun and switch to a less dishonest source of information? The second relates to the moral responsibility of the author of such carefully filtered data. Since the person most likely to uncritically accept such dishonesty is one already predisposed to the author’s viewpoint, is it fair to reward such faith with misinformation?

The non-ideological use of data is very different. Rather than starting with a solution and looking only for supportive data, it may start with a problem. It then asks what the possible solutions to that problem are. Data are used to assess the evidence for these possible solutions. The emphasis remains on finding the best answer to the problem. For instance:

- Are there people who cannot find affordable health insurance?

- Will the production of greenhouse gases stabilize and start back down?

- How do cities like Milwaukee prosper?

- How do we have schools that work for all kids?

In contrast to answers derived from ideology, the answers from honest research are often ambiguous. A fair assessment of the possible solutions will often include nuances and uncertainties.

Clean data is usually hard to find regarding public policy questions. For instance, states with right-to-work laws are far more similar to each other in many other dimensions than to states lacking those laws. Thus it is very difficult to tease out any differences caused by those laws.

In most public policy issues it is not possible to set up an experiment, where subjects are randomly divided into two samples and the result of applying a policy to one of the two groups is compared to the other group. Even where such experiments are technical feasible, for example, by randomly assigning students to different schools in order to judge which schools are most effective, such an experiment is likely to be both politically impossible and educationally undesirable.

While the free market cult is the most prominent ideological player in Wisconsin today, it is not the only one. The right wing has no monopoly on ideology. On the left, an ideology that opposes charter schools, testing, and the Common Core has become influential in public education.

If there is a single theme that runs through the Data Wonk articles it is that of ideology. Making decisions based on an ideological view of the world is likely to lead to bad decisions. But for Data Wonk, at least, ideological decision making is the gift that keeps on giving, offering a steady stream of raw material for future columns.

Common Core itself is a great example of your point. Starting many moons ago and probably still circulating today was a Facebook video of a frustrated teacher awkwardly trying to use “the Common Core way” of teaching math. Since it was a different approach than the one she was previously rote-taught it was “hard”. The example got used as a way to illustrate how bad “Common Core” was and how it would so very badly mess up the next generation. What the teacher was struggling with was her districts’ or DoE’s way they had implemented it, but that wasn’t what was being complained about.

However, an objective look at the situation and an independent reading of the Common Core itself reveals that it is not a prescriptive method but rather a set of goals that one should achieve at a certain point in the educational journey. http://www.corestandards.org/Math/

Imagine my horror when I read it myself and saw that it expects people to learn and count in this thing called “Base 10”.

I remember a day in high school, which was a long time ago, when all the cool girls, the ones in the great clique, came to school wearing little black dresses. That was a Great Day, one of the finest of my young life. The angels sang.

Not too long after, within months or so, a day came when almost all these same girls came to class with their hair cut, with short hair. That was a very sad day. My heart wept.

Ultimately, I learned that people like to follow the group. They do what is popular or fashionable, at least when it is something that isn’t life or death, to them at least. They are easily manipulated by those who can do that.

People are lemmings. But a person is not. To reach the hearts and minds of a group, you have to out-manipulate the manipulators. Reagan understood this. In the end, the side with the strongest argument, the best message will win. In the long run.

None of this makes Smith any less correct or Marx any less wrong.

Actually, now that I think about it, they were wearing those ’70s tight black pants, not dresses. Same effect.

Hahaha! That story was a great way to start the day, mbradley. Poignant illustration.

An interesting point this article seems to neglect about data-driven results: the questions asked are very much used to influence the conclusions drawn and information collected. Additionally, all conclusions and trends observed from data fall within various levels of confidence. Any reported result contains (usually) between a 1 and 10% chance of being completely off-base. No matter what.

A given ideologue cannot say much with certainty, “data” or none.

An ideologue does not want to be confused with facts and reality. Emotions will be used instead to manipulate with lies and a divide and conquer strategy. They also resort to killing off the messengers, fact gatherers, and researchers and use propaganda instead. An example of this is killing off jobs in DNR, data gatherers, and regulations that protect the health, safety, and welfare of the population and not knowing the history of their purpose. Instead, the bullet item propaganda fills the void with nonsense, and censor police remove words and phrases from use and practice. Ideologues thrive on ignorance and keeping a population in this mode is to their benefit.

In general, many voters today have busy lives with work and family, and lack time and effort needed to sort for facts. Newspapers used to supply some daily fact information but have greatly diminished in this role along with their credibility. People are more emotion driven in decision making and are more easily manipulated with propaganda that is filled with lies and deceit.

There are many that profit for political theology, lies, and deceit. All we have to do is follow the money trails but even that is being covered up as new laws are implemented by politicians to protect the deceivers and thieves.

MBradley: I disagree with your statement, ” Reagan understood this. In the end, the side with the strongest argument, the best message will win. In the long run.” There is no explanation of why Reagan should be considered correct. It is also important to understand that much of a message’s success is in its appeal to emotion. So success is not necessarily related at all to even the best information, although the best information should factor into the discussion. While data is not the only important part of political analysis, the dishonest portrayal of situations and resources is rampant. If someone takes a highly partisan position and successfully distorts facts to their benefit, then winning is a sad thing indeed.

You also said: “None of this makes Smith any less correct or Marx any less wrong.” Without some context this statement appears to be mere grandstanding. Perhaps, you felt there is not enough space on this page to fully explain your views. That would be understandable. Still, you could do much better than this.

Adam Smith is one of the most misquoted and poorly attributed economists out there. Some versions of his “An Inquiry Into The Nature And Causes Of The Wealth Of Nations” have been abridged in a way meant to change his apparent views. In reality, Smith supported free market principles, but also criticized much of the practices of human behavior in the marketplace.

Consider this Smith quote, “People of the same trade seldom meet together, even for merriment and diversion, but the conversation ends in a conspiracy against the public, or in some contrivance to raise prices. It is impossible indeed to prevent such meetings, by any law which either could be executed, or would be consistent with liberty and justice. But though the law cannot hinder people of the same trade from sometimes assembling together, it ought to do nothing to facilitate such assemblies; much less to render them necessary.”

Any who blindly refer to Adam Smith as an uncompromising champion of business to do whatever it likes is not being honest. At the very least, and like most people, that person has not read Smith’s essential work and its hundred of pages, most of which requires considerable thought and reflection.

My experience informs me that, while there are some on the left who are driven by ideologies, the real power and force of ideology in recent years lies with the right. There is no question, in my view, that a particular narrative packaged as a conservative viewpoint has been successfully marketed as entertainment and a convenient political position. This packaging has been helped by the structure of national politics, which favors territory over population in the Senate. Combined with the expiry of post-WW2 world dominance, we now have a national discourse that leads nowhere, and is a danger to the Republic. Again: it is false to accuse the left of ideology comparable with the right.

As someone who spent their formative years studying social sciences, I can’t help but think that your critique of ideology stems from a lack of understanding the concept. We all have ideologies that we subscribe to in some form or another. Just call it our ethical foundation. Otherwise it would be impossible to understand the world or have an opinion on issues. Capitalism is based on ideology, otherwise we’d have no justification for our current methods of production and wealth distribution. Christianity as followed by most is a sort of ideology. The Bill of Rights is an ideology of sorts for most Americans. The positivism that this column is based on is an ideology, and a pretty scary one at that.

The question “How do cities like Milwaukee prosper?” is a perfect example of how our understanding of facts and data is subjective and why blind positivism is a problem. A lot of people on here would say that GDP or median income and lots of new skyscrapers is a good indicator of prosperity. There are a lot of us that would say wealth distribution, poverty rates, and quality of life indicators are more important. Neither is more “right” based on the facts. A healthy society encourages lots of competing ideologies and gives people the space and opportunity to change viewpoints over time. A society “without” ideology is just a dictatorship under another name.

To Sam: I think it is a mistake to equate ideology with values or an “ethical foundation.” Doing so makes the concept meaningless. One test is whether we are willing to change our minds when new evidence comes in. Another sign is when people fall in love with their solutions and lose track of the problems they were meant to solve.

To Steve: I would tend to agree with you if the discussion were limited to state and national issues. When we look at a city like Milwaukee, ideology from the left is a major hindrance to finding ways to make the education system more effective. The number of people emerging from the educational system without the skills they need to prosper in today’s environment is, I believe, a major threat to Milwaukee’s future. (These thoughts triggered by listening in to a school board discussion of a charter school application last night).

Anyway, thanks for your comments.