The Charter School Advantage

A new study shows charter schools outperform MPS schools. But they still trail the average state school.

The recently issued Urban Charter School Study from Stanford’s Center for Research on Education Outcomes (CREDO) has good news and bad news for Milwaukee education. The good: as a group Milwaukee charter schools are outperforming traditional public schools. The bad: this differential is not great enough to bring those students up to the level of average students statewide.

A word about the study’s methodology. Most studies of charter school outcomes depend on finding schools with more applicants than available seats. Under the law, these schools are required to choose their students using a random lottery. The studies track the two groups of students—those randomly accepted and those rejected—and compare their subsequent progress.

This traditional approach has two limitations. First, it limits the number of charter schools that can be studied to those with a surplus of applicants. Yet most charter schools are able to accommodate all applicants. The second—and more serious—is that it may not tell much about other charter schools. If parents pick charter schools that are most effective (the evidence for this is weak) the sample of charter schools itself may be biased, with the most effective charter schools.

CREDO gets around this limitation by matching a database of a million charter school student records with a comparison group of traditional public school students. As the CREDO report explains, its “matching process uses the Virtual Control Record (VCR) protocol, matching each charter student with up to seven traditional public school students based on prior test scores and demographic characteristics.” The report says it is thereby able to match over 80 percent of the charter school students in the analysis.

CREDO applied this methodology to 41 urban regions, including Milwaukee. There was considerable variation in the results from one region to another. In a few regions, charter school students did more poorly than those in traditional schools, but on average the charter school students gained more than the public school peers. Milwaukee charter schools followed the national pattern.

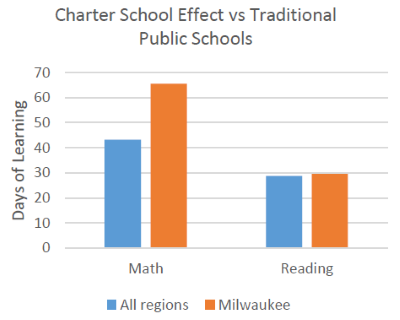

The chart to the right shows the charter school advantage for all regions and for Milwaukee in mathematics and reading. On average, Milwaukee charter school students annually gained the equivalent of about 65 extra days of learning in math compared to students in traditional public schools. In reading they gained an extra 29 days.

The report also breaks out the charter school effect for various sub-groups. On the whole students in groups considered disadvantaged had a greater charter school effect, but there was considerable variation.

Nationally, the extra days of learning increased the longer a student was in a charter school. The report did not break out this effect by region.

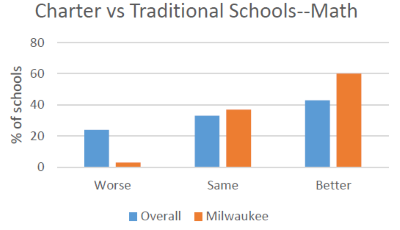

When individual schools were compared to their traditional school peers, Milwaukee charter schools stacked up well. Only 3 percent of Milwaukee charter schools did worse in math, while 60 percent did better, as shown in the graph to the right.

There were similar school results for reading, although the percentage of schools rated better drops to about 40 percent.

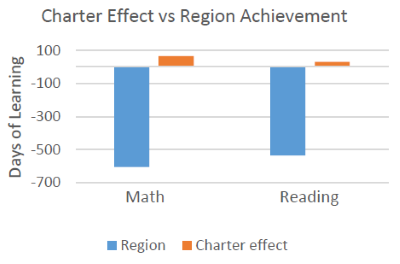

The bad news is that Milwaukee students have a very large deficit compared to the rest of the states and the charter school advantage is not sufficient to overcome this. As the report says:

…students enrolled in charter schools in Cleveland, Miami, and Milwaukee can expect to see higher levels of academic growth than expected in their region’s local TPS, but this charter lift is not enough for the average charter student to offset the achievement deficit of the region relative to the rest of the state in both math and reading.

By contrast the report identifies regions faced with large region-wide achievement deficits relative to their state’s average, but whose “charter sectors appear to provide their students with strong enough annual growth in both math and reading that continuous enrollment in an average charter school can erase the typical deficit seen among students in their region.”

The CREDO report does not identify the individual charter schools in which an individual student is likely to do better — or worse. The Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction does publish school report cards that rate schools on various measures. Unlike the CREDO methodology these do not attempt to untangle the school effect from the student effect. In an earlier report, I listed all the Milwaukee schools—traditional and charters and how they did on two scores from the Department of Public Instruction. There was a strong correlation between the DPI Achievement score and the prosperity of the families a school serves.

There are three active charter authorizers in Milwaukee: Milwaukee Public Schools, the Milwaukee Common Council, and UW-Milwaukee (a fourth potential authorizer, Milwaukee Area Technical College, has shown no interest in authorizing charter schools). In addition, schools authorized by MPS fall into two groups: instrumentality charter schools in which teachers and other staff are employed by MPS and non-instrumentality charters which hire their own employees.

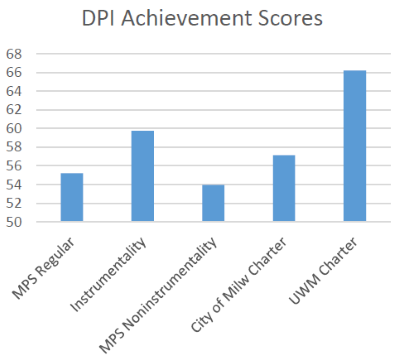

The chart to the right shows the average DPI Achievement score for each of these groups of schools. As a group, charters authorized by UWM outshine all the others on this measure. Recently the charter program run by the Milwaukee Common Council has come under attack by anti-charter groups because several of its schools fared poorly on the Achievement Scores. Still, on average, its schools outscored MPS regular schools and non-instrumentality schools.

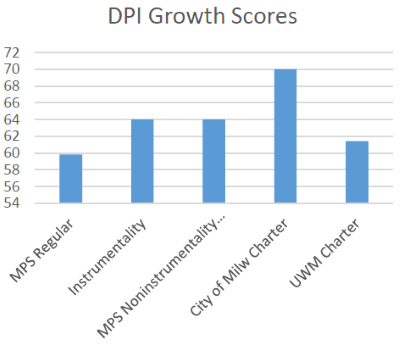

Probably the DPI scores that comes closest to the CREDO methodology are its Growth scores in reading and math. These are based on how well individual students’ test scores improve from one year to the next. These also have limitations; for instance, high schools are excluded since they only test 10th grade students. The Growth scores shows City of Milwaukee charters with the highest average scores, likely reflecting the emphasis placed on student growth by the city’s consultants. As the chart to the right shows, all segments of charter schools outperform MPS regular schools when it comes to student math and reading growth.

The MPS instrumentality charter schools exist in a kind of limbo between regular traditional public schools and true charter schools. (CREDO tells me they treated them as charter schools.) So far as I know, none of the instrumentality schools has a board with legal responsibility for governance of the school. Applicants for instrumentality charter school status have mainly come from two groups. The first are existing MPS schools looking for more autonomy and hoping to win chart development grants. The second is MPS teachers with a particular vision for a school or a desire to serve a particular population.

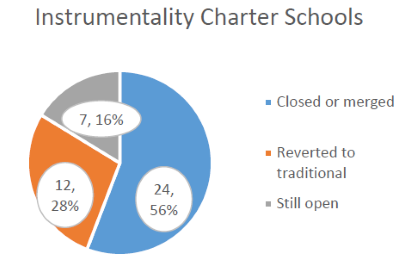

Over the years, instrumentality charters have suffered considerable attrition. Of 43 that opened, only seven remain, three converted traditional schools and four small teacher-led schools. As the chart to the right shows, the others were closed or reverted back to traditional schools.

One likely factor in the high attrition rate, particularly with the teacher-led schools, is that the union contract made it hard to assure that new staff shared the vision of the founders, particularly during layoffs when senior teachers had bumping rights.

It is unclear whether charter status had a positive effect on student achievement at instrumentality charters, as might be implied by their higher average Achievement and Growth scores compared to traditional MPS schools. The higher score is likely to reflect selection bias—that low-achieving instrumentality schools were switched back to traditional schools.

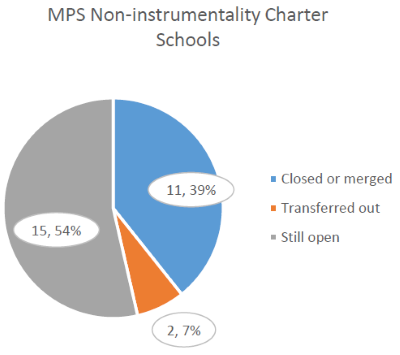

Attrition among the MPS non-instrumentality charter schools has been much lower, as shown in the graph to the right. A majority of the schools that opened are still running.

It is unclear whether MPS will continue to be a major player in the world of charters. The tone on the Milwaukee School Board (on which I once served) has become increasingly hostile to instrumentality charters, particularly if the proposal comes from someone with past associations with any of the national education reform groups, such as Teach for America, or from one of the national charter organizations. The fact that this past year MPS received only two applications for charter schools (compared to an average of about 9 per year since 200) suggests the word is out that MPS is not welcoming of charters.

The results from the CREDO study and previous research, as well as the DPI report cards, suggest that charter schools can contribute to better outcomes for Milwaukee’s children. However, governance is no magic elixir that in itself allows a school to master the challenges facing urban education. Yet it seems clear that the freedom allowed by the charter school approach can lead to interesting results if allowed to flourish.

Data Wonk

-

Life Expectancy in Wisconsin vs. Other States

Dec 10th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Dec 10th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

-

How Republicans Opened the Door To Redistricting

Nov 26th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Nov 26th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

-

The Connection Between Life Expectancy, Poverty and Partisanship

Nov 21st, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Nov 21st, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

What is the definition of an instrumentality school? Also, I would emphasize that these are charter rather than voucher schools, so they are for the most part still in the public school realm.

Thanks.

Wisconsin law says: “the school board of that school district shall determine whether or not the charter school is an instrumentality of the school district. If the school board determines that a charter school is an instrumentality of the school district, the school board shall employ all personnel for the charter school. If the school board determines that a charter school is not an instrumentality of the school district, the school board may not employ any personnel for the charter school.”

I am not a statistician but here is something I have always wondered. To really study the effects of any “choice” alternative, be it charter or voucher, wouldn’t we have to be able to randomly assign kids from the overall school population to different schools, and compare outcomes? It seems plausible to me that the children of parents confident and savvy enough to seek out an alternative like a charter school may already be children who would have performed relatively better in any setting they were in, due to that parent involvement. If their parents can get them to a better learning situation than they would otherwise have been in, it is of course great for those students to have a better educational experience. But are their improved outcomes because of the school, or because most of the other students in the alternative also have similarly involved and motivated parents? My impression is that a big challenge in effectively educating low-income students is that many of the adults in their lives don’t have the wherewithal, for whatever combination of reasons, to consistently help support their learning. Of course this is not always the case, but it often is. If charter schools have found a way to tap into family resources or to help enable low-income families to do more to support their children’s education, those successes should be shared with other schools. That was supposed to be part of the policy reasoning behind charter schools in the first place, to enable innovation that could inform the system as a whole.

Joanne…An instrumentality school is typically started by existing teachers of the district who want the additional freedom that charter status affords (such as using an alternate teaching method, a different textbook program, or different school hours). The teachers already are employees of the district and, were the charter school to close or not be renewed, they would remain district employees. The school itself would convert back to a regular district school.

Non-instrumentality schools are charters that are proposed by outside groups such as social services agencies, for-profit entities, or educators who are not currently district employees. Their employees may not become employees of the district. If a non-instrumentality school closes or does not have their contract renewed, the entity that started the school and its employees part ways with the district.

In either case, the students of these schools are considered students of the District and given the same opportunities as students who attend the district’s traditional schools. Including the fact that charters are not allowed to have entrance requirements and the school is subject to the open enrollment rules including a wait list/lottery system if the school reaches capacity. Charter students also have the same due process rights for discipline matters as traditional district students. (This is all by state law). Hope this helps.

This article and its “findings” raises red flags on one sidedness against MPS and is concerning on the impact of out of state money and agendas on Wisconsin public schools. Excerpted from article by Dom Noth, Labor Press, from a few years ago:

“For candidates such as Spence and Joe Dannecker (running again this year) and Barbara Horton and Ken Johnson (not running again), this network had been crushing opponents by sheer power of money. In 2003, it had a failure of its most prominent voucher advocate, John Gardner. In 2001, another failure had bounced Bruce Thompson from the board – yes, the same candidate now back with big money in the 2007 at-large race. (And how Thompson connects with the Spence case is intriguing.)

Working through a nonprofit and a fund-raising conduit operating out of the same offices (and headed by such familiar voucher names as Howard Fuller and George and Susan Mitchell), aided by outside parties such as the Metropolitan Milwaukee Association of Commerce, the network allowed its candidates the fanciest brochures and media ads while the public assumed that all the concern stemmed from actual residents and users of the public schools, not rich private-school advocates in Arkansas and Florida.

The treasurer/administrator for this voucher conduit remains none other than Thompson. The millionaires and billionaires sent checks to the conduit, designating how much should go to whom. The conduit deposited the funds and then issued checks to the candidates.

Spence’s delayed filing made him seem a minor player in all this hullabaloo, but the now-filed campaign reports reveal he wasn’t – and also reveal that many of the contributions should have been reported prior to the 2003 election. In 2003, the belated reports reveal, Spence received $11,495 from out of state, twice what the news media thought, much of it through the conduit, and $2,520 more from state residents living outside the city. The public didn’t know before it voted because he filed late.

This background sets the table for looking at campaign reports for 2007 filed eight days before the April 3 election. (As of this writing these campaign filings, the last before the election, went unreported in Milwaukee newspapers.)

These reveal that the conduit has quieted way down, as has the issue of voucher schools.

But apparently Thompson’s role as conduit treasurer helped keep those familiar out-of-state names interested in him. This time they’re giving directly to his campaign, helping him raise a whopping $66,522 so far in 2007 – and more than $27,400 from outside Milwaukee. There’s also $7,500 (the max) from three “friends” committees of school board member Danny Goldberg and the non-running Horton and Johnson (who seemed to have a lot of campaign money left over). And carryover from late last year.

His opponent for the at-large seat, Bama Brown-Grice, would normally be applauded for her fund-raising in 2007, $24,658. It is eminently grassroots local. Almost half came from Milwaukee residents giving $5 to $500 – in fact, some 100 citizens gave an average of $125 each. The other half of her money comes from local committees – candidates she beat out in the primary and labor groups (SEIU, AFT, AFSCME, MTEA).

By contrast, Thompson had about half the Milwaukee contributors, many CEOs or noted investors and political players, who on average gave nearly $300 each.

Typically, school board candidates rely on door-to-door slogging and local printers to get the word out. Thompson has so much money that he has reached to Austin, Texas, to hire a major player in political advertising, Fero Hewitt Global, which so far has been paid $29,500 for slick brochures and media ads that will mainly hit the week before the election.

http://www.milwaukeelabor.org/in_the_news/article.cfm?n_id=003

Some good news for MPS- http://urbanmilwaukee.com/pressrelease/mps-high-schools-take-states-top-2-spots-on-washington-post-best-list/