The Impact of Right to Work Laws

State Republican leaders want to pass such a law. What will be the impact on jobs and wages?

Twenty four of the 50 states have so-called “right to work” (RTW) laws. These laws discourage union membership by prohibiting contracts between private companies and their unions that require employees to pay dues to the union. Often they also prohibit the employer from deducting union dues from workers’ pay.

Republican leaders have proposed such a law for Wisconsin. Given GOP domination of the legislature, it seems likely to pass. Although Gov. Scott Walker has said RTW is not a priority for him, it seems unlikely he would veto it. How will this affect Wisconsin?

In theory, RTW would work by weakening unions, thus depressing wages and benefits. Companies seeking low labor costs would be attracted to Wisconsin by lower wages and benefits, and by a reduced threat of unionization. As a result, Wisconsin’s jobs would increase. A similar argument is made against increasing the minimum wage—that lower wages equal more jobs.

In practice, assessing the impact of RTW on either wages or jobs is very challenging. The RTW states differ from non-RTW states in numerous other ways. Geographically, states with RTW laws largely fall into two groups (1) all the members of the Confederacy and (2) a broad band of states running through the Great Plains and Rocky Mountains. There are no RTW states in the Northeast, none on the Pacific Coast, and there were no midwestern industrial states, until the passage of RTW laws by Indiana and Michigan.

The distribution of oil and gas production is another example of a complicating factor in measuring the effect of RTW laws. States like Alaska, Louisiana, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Texas, and Wyoming have gained employment from booming oil production, but that may change with the recent collapse of oil prices. Either trend would have an impact when comparing employment and wages in these states with others.

Multiple regression analysis offers one way to sort out the effect of the RTW laws from the many other differences between the states. The most ambitious attempt I found was published in 2011 by the Economic Policy Institute. It concluded that wages in RTW states were 3.2 percent lower (about $1,500 for a full-time worker), the rate of employer-sponsored health insurance was 2.6 percent lower, and the rate of employer-sponsored pensions was 4.8 percent lower.

For non-unionized workers, the wage penalty was 3 percent, the health insurance penalty was 2.8 percent, and the pension penalty was 5.3 percent. The rate of union membership in non-RTW states was more than double that in the RTW states. Thus the better pay and benefits may reflect the need among employers without unions to compete with unionized employers for workers.

The EPI study’s findings thus reinforce a key part of the economic theory behind RTW—that it drives down overall labor compensation. One possible concern with this study is that the EPI–an ally of unions and opponent of RTW laws—may have missed some factor influencing wages and benefits which, if included, would have eliminated the RTW difference. If so, I would expect to find a critique from one of the many organizations advocating for RTW legislation. So far as I can tell, no such critique has been published.

Instead, advocates rely on comparisons that make no attempt to compensate for factors other than RTW. An example of how this works is included in the most recent Rich States Poor States authored by Arthur Laffer, Stephen Moore and Jonathan Williams and published by the American Legislative Exchange Council. It compares the economic performance between 2002 and 2012 of the RTW Midwestern states–North Dakota, South Dakota, Iowa, Nebraska, and Kansas—with that of the “forced unionization states”–Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Ohio, Wisconsin, Minnesota, and Missouri.

But the economies of the two groups of states are very different. The RTW states are heavily agricultural. The 2002-2012 period was a very good one for American agriculture, with net incomes doubling in real terms. In addition the RTW group includes North Dakota whose booming oil industry allowed it to far outperform any other state. By contrast the non-RTW group was heavily industrialized during a period when manufacturing employment nationally dropped by 24 percent.

Testing the second part of the model—that lower labor costs lead to more jobs—runs into the same problem of trying to isolate the effects of RTW from other differences between states. Again, advocates of RTW solve this problem by ignoring it. For example, they conclude that the Midwestern states with RTW grew more because of RTW, not because they discovered a new source of oil or were heavily agricultural at a time when farming did very well.

In theory one could approach this issue by looking at states that passed RTW and compare jobs before and after the law took effect. But one must be careful that some other change happening within the state does not explain any change in jobs.

And in the past decade only Indiana and Michigan passed RTW laws—both in 2012. When Indiana was considering its bill, the state chamber of commerce published a paper arguing that RTW would have led to higher employment and compensation, mostly based on growth rates from 1978 to 2008. As with the Laffer report already mentioned, this paper made few attempts to account for other possible causes for differences in the period it used.

My first chart shows Indiana and Michigan job growth between the January 2010 when jobs started to recover from the recession and the start of 2012. For comparison, I added US, Wisconsin and Minnesota job growth, During this early recovery period, job growth in Michigan and Indiana slightly bested Wisconsin’s and almost equaled national growth (although Minnesota was the Midwestern standout).

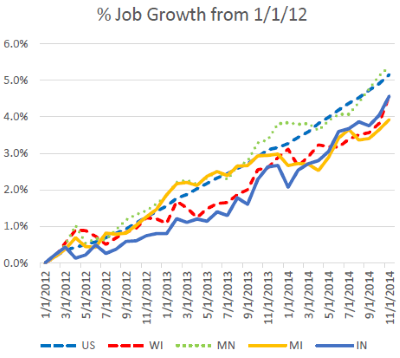

My next chart tracks Indiana and Michigan jobs starting in 2012, when they passed RTW legislation. If anything, they fell further behind national job growth and that of Minnesota, which continued as the regional star. The safest conclusion is there is no evidence of a positive effect on jobs from their adoption of RTW.

It could be argued this comparison does not allow enough time for the Indiana and Michigan RTW laws to have a positive effect on jobs. Can we look to other states? The problem is that no other state has passed RTW legislation since Oklahoma did so in 2001. Since then Oklahoma’s manufacturing employment dropped 17.7 percent. Would it have dropped even more without RTW? Hard to say. In the same period, Wisconsin, without RTW, saw its manufacturing employment drop by 16.9 percent.

Perhaps because the evidence in support of RTW as a job creator is so weak, its advocates fall back on a faux-libertarian ideological argument, casting themselves as worker advocates. This is reflected in the name they have chosen. However, right to work laws give no one a right to a job. Rather, the laws ban employers from signing agreements that require workers to join or pay for unions. In the tug-of-war between capital and labor, they move the balance of power in the direction of capital.

In advocating for RTW, the economist hired by the Indiana Chamber of Commerce condemns “governmental constraints on individual employment bargaining.” But that phrase perfectly describes what RTW does: it’s a government constraint on the ability of private parties to negotiate a contract. As a commentator at a libertarian journal commented, “If employers choose to conclude union-shop contracts with unions, what gives the Indiana legislature the right to interfere?” Similarly the editor of the libertarian publication Reason argued, “The ideal role for the government in business-labor relations is to stay the hell out of it and let the parties work things out themselves.”

An analogy might be passing a law banning mandatory condo association fees. That law would likely spell the end of condominiums, by allowing individuals to enjoy the benefits of the association without paying for them. In economics, this is known as the “free rider” problem that plagues a range of social goods and services, including actual free riders who take transit lines without paying for them. RTW discourages unions by introducing the free rider problem. If a majority of employees decide that union representation is worth paying dues, under RTW they have no ability to limit the union’s benefits to those willing to pay.

A recent Milwaukee Journal Sentinel article by Alan Borsuk noted that the number of students in conventional Milwaukee Public Schools had shrunk over the years even as enrollment in choice and charter schools, including those authorized by MPS had increased. This means that the proportion of teachers represented by the MTEA had been steadily declining even before Act 10 kicked in. Over the years, as a member of the school board I voted to authorize a number of so-called “instrumentality” charter schools. These are charter schools that employ members of the union. In the end, most of them have closed. One factor in the failure of unionized charter schools has been that hiring rules under the labor contract made it difficult to pick staff who were committed to the unique mission of the school. In essence, the union rules served to strangle its most entrepreneurial members.

On an occasion when I visited the MPS’ “Urban Waldorf School,” I discovered that the sole remaining Waldorf-trained teacher was on sabbatical. Soon after the school changed its name and then closed.

The challenge for the labor movement in the 21st Century is to find ways to encourage rather than discourage innovation and market responsiveness within a company (or school, etc.) that is unionized. Failing to do so is likely to lead to continued declines in union membership, regardless of the fate of RTW legislation.

Data Wonk

-

Life Expectancy in Wisconsin vs. Other States

Dec 10th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Dec 10th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

-

How Republicans Opened the Door To Redistricting

Nov 26th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Nov 26th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

-

The Connection Between Life Expectancy, Poverty and Partisanship

Nov 21st, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Nov 21st, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Is there strong evidence showing that Wisconsin is losing in-state companies to states in the Midwest with right-to-work laws? Or that companies, when choosing where to locate/re-locate, are choosing right-to-work states in the Midwest and not Wisconsin only because of that issue?

Two comments. First, regarding the EPI study, I’d love to know if they accounted for the differences in the cost of living and the ratio of wages to that cost of living. For example, if wages in state x were 2.5% lower than state y, but the cost of living is 4% lower, they’d actually have a net positive income over state y. I was thinking about this the other morning when I heard someone try to use the comparison of wages in RTW vs non-RTW states since many RTW states have lower cost of living.

Second, without getting too specific, I can speak from personal experience in my daily job, that I and my company lose business on a regular basis because our costs for union labor far exceed our non-union competitors. It is more than just the labor costs, we also have many other restrictions that hinder our ability to do business. It’s good for many of our union members (although not all) but it has a sizable impact on the amount of business we do. Ultimately it affects the size of our branches across the country and the number of people we have working for us. There’s certainly a trade off.

Lose business to states with RTW laws like Indiana and Michigan? Does that mean your company supports RTW in Wisconsin?

I challenge the idea that “hiring rules under the labor contract made it difficult to pick staff who were committed to the unique mission of the school. In essence, the union rules served to strangle its most entrepreneurial members.”

Hiring in MPS schools, even under the old contract, which now does not exist, where made by a committee of staff, administrators and the community with administrators having the final say on hiring.

Rarely did the union rules inhibit like minded staff from being hired in a school with a strong mission.

Bruce seems to be looking for a middle road analysis and union bashing always seems to foot the bill for liberal “wonk” types.

AG: On your first question, cost of living is one of the factors they single out: “In a regression framework, we analyze the relationship between RTW status and wages and benefits after controlling for the demographic and job characteristics of workers, in addition to state-level economic conditions and cost-of-living differences across states.”

Your second point gets at a long-standing frustration of mine, that unions don’t seem to recognize that they are part of supply chains and that increasingly supply chains, not companies, compete. Thus if your union makes your company less competitive, it is sabotaging its own future.

PMD: so far, there doesn’t seem to be any sign that job growth in Indiana and Michigan was affected by RTW but it is early. The evidence for companies insisting that states have RTW is largely anecdotal and hard to separate fact from fiction.

Thanks for addressing that BT. I hadn’t had a chance to look at the EPI study myself but I’ll try to find time to nitpick it later! 🙂

PMD, I am unaware of any official stance my company has on RTW, nor would I think they would make one. I only speak of my personal experience as I work across the country and internationally with [often] union represented workers. Many times we compete in regions in which our competition is not represented by a union. There are sometimes advantages to that, but more often than not, there are more negatives.

Thanks for sharing AG. I imagine groups like WM&C and the Chamber of Commerce support RTW, but are many companies taking a public stance on it at this time? You read about it almost daily but it’s always about what Walker and legislators think about it.

Fonscz,

In recent years, MPS did change the contract so that school communities could interview applicants, but this was limited to certain periods and did not apply to reductions in staff where teachers had bumping rights based on seniority. I heard from a number of principals and teacher leaders who complained that the teacher they were developing in the spring with others who had no affinity for the school’s mission.

Inadvertently I think you put your finger on a major obstacle to improvement: the reaction that any criticism is teacher or union bashing. How can one hope for improvement in such a culture?

Thanks for posting his Bruce!! Great analysis and ironically, I sat in a debriefing on the EPI report yesterday with fellow Democratic Legislators. Gordon Lafer from the University of Oregon presented with stunning facts and data about how much of a failure RTW is, especially on proponents major claims: job attraction, wages, competing in global markets. Their side cannot produce one shred of evidence. And thank you for clearing up the confusion about the data analysis. EPI used a data set of about 21,000 workers from different states in 2009. Regression analysis by definition, is the use of statistics by holding other factors constant, like Bruce smartly pointed out. Bottom line takeaway: RTW changes laws so that if a union negotiates a contract at a company, they would be prevented from charging employees for the cost of administering the contract terms. That means, no mediator hired. No oversight if the employer violates the contract or abuses the process. No protection of workers in other words and dilutes the wages and benefits of a contract negotiation. It creates a Free Loader problem. Right now, under Federal laws, a union already cannot force you to join and cannot force you to pay dues. But, if you get the benefits of a contract, you gotta chip in to help pay for the work of a contract negotiation. Seems normal and fair to me. Imagine playing poker, and refusing to up the ante, but hold your cards so you can still win jackpot. Or, refusing to pay Social Security taxes but expecting a check in your older years. Even business groups like WMC, would never provide benefits/services to a company who refuses to pay their membership!! All this does is kill union power, drive down wages for the working class, and ultimately, attack a key funder and supporter of Democratic Party politics, giving corporate bigwigs more control over our lives. Not that they would screw anything up, say, like the stock market tanking over illegal and high risk investments, or…blocking health insurance reforms for everyone, or making profits off a bubble housing market and sending ordinary families into bankruptcy…just sayin!!

Please check out this great Op ed by Gordon Lafer. Please note, Jim DeMint if you remember, was leading opponent of using Federal spending alleviate the recession and fallout from a crashed stock market and housing collapse. If Obama said it was a nice sunny day, he would claim its raining out!! http://www.politico.com/news/stories/0511/55654.html

Why is there all this talk that says supporters of RTW laws never back up their claims? In a 10 minute academic research database search I found numerous peer reviewed studies that show a lot of positive outcomes from RTW laws.

One study showed Idaho had significantly more manufacturing job growth attributed to lower union density caused and/or contributed by RTW laws passed 1986. Dinlersoz, E. M., & Hernandez-Murillo, R. (2002). Did “right-to-work” work for idaho?

Another study found that states that pass RTW laws have a lot lower percentage of companies using contractors and other “a-typical” work types. This is because more companies in non RTW states use contractors to avoid some of the costs of hiring union workers. This means more workers working without full time benefits. Surfield, C. J. (2014). Government mandates and atypical work: An investigation of right-to-work states. Eastern Economic Journal, 40(1), 26-55.

Here is a story that directly contradicts the EPI study. This study shows state wages are higher in RTW states than non RTW states. Reed, W. R. (2003). How right-to-work laws affect wages. Journal of Labor Research, 24(4), 713-730.

Here’s an interesting study that is specifically looking to examine the factors often left out of studies on RTW states. Specifically, they focus a lot on geographic and spatial variables that come into place. The biggest thing I noticed that, besides the fact that they talk about some factors that affect RTW outcomes that the EPI study does not address, is that RTW generally has very different effects on different industries. This means it affects some industries like agriculture and construction differently than say service industries and professional/management industries.

Kalenkoski, C. M., & Lacombe, D. J. (2006). Right-to-work laws and manufacturing employment: The importance of spatial dependence. Southern Economic Journal, 73(2), 402-418.

Besides that, there’s a lot of talk about the “Free Rider” who mooches off the work of the Union without paying for the benefits. How about the “Forced Rider” who may not get as good pay and benefits because he’s stuck with the collective bargaining agreement instead? When you collectively bargain there are often people who get less reward for their work than they would have in a “meritocracy” or other system based on individual performance or abilities.

AG: Same study you referenced, said this:

“A 2002 Dinlersoz and Hernandez-Murillo study that examined the

impact of passing RTW legislation in Idaho in 1986 also indicated

an increase in the share of manufacturing employment compared to

overall employment within the state. Again, however, the authors

indicate this as merely a shakeup of the overall employment mix within the state (a movement

of jobs from other industries to manufacturing), rather than an absolute increase in overall

employment. In the case of Idaho specifically, the demise of the state’s timber industry in the

1980s, rather than passage of RTW legislation, may have played a key role in this change in the

employment mix. ”

IN OTHER WORDS: Timber jobs fell apart given foreign competition, RTW weakened manufacturing unions, thereby making attractive for firms seeking lower wages, even though increasing number of jobs. AND, that data is over TEN YEARS old…bet a beer, that as Idaho loses manufacturing jobs, they will not go to other RTW American states, but to China, India, Mexico, etc. This is what is meant by race to the bottom…as a State, your goal is to not to catch the wave that leads to lower incomes for your citizens in short run and setting the table for companies leaving for China over long term.

And this confirms, evidence of lower incomes and worse, lower benefits. Exactly as RTW oppositino has stated. a Looking at actual data, looks sure like Idaho had more robust jobs and economic growth BEFORE PASSING RTW NOT AFTER

IDAHO: Income in the state grew much more slowly after passage of the measure, according to Bureau of Economic Analysis data.

Between 1985 and 2013, per-capita personal income grew about 40 percent, adjusted for inflation. But in the 28 years before right-to-work, it grew 67 percent.

And in terms of benefits, the change was even more dramatic.

From 1957 to 1985, total employer contributions to private pensions, insurance, unemployment and other benefits grew by more than 400 percent, adjusted for inflation. Between 1985 and 2013, those contributions grew only 60 percent.

Read more here: http://www.idahostatesman.com/2014/12/14/3541291/economic-fallout-of-right-to-work.html#storylink=cpy

Finally, AG you reference “How about the “Forced Rider” who may not get as good pay and benefits because he’s stuck with the collective bargaining agreement instead? When you collectively bargain there are often people who get less reward for their work…”

Please share with us: Where do you have data or evidence of this? With exception of unionized public school teachers in states with performance bonuses (which are on top of collective bargained wages/benefits for all), what industry, what union, what contract and what group of ‘forced rider” workers…has examples of people being stuck with worse wages/benefits as result of a collective bargaining agreement??

Rep Zepnick, thanks for the response and I appreciate your passion. My listing of those studies was to refute your claim that no shred of evidence has been given in support of the benefits of RTW. All of those studies point out benefits of RTW, including the study focused on Idaho. Like most things that affect the economy, it’s a mixed bag with trade offs. Yes, they do mention a decline in the timber industry sending more workers into manufacturing, but manufacturing doesn’t appear out of nowhere. The purpose of the RTW was to make the state more attractive for businesses in order to lure more and help those that exist to grow more.

Regarding wages from Idaho, I never said they rose in the state. But I’d like to point out that you can’t take a state in a bubble and compare two time periods without taking into account other factors that may have affected them during that time period. All of these studies attempt to do so, even the EPI study.

I can discuss the outsourcing all day, so to avoid that I’ll leave the china discussion for someone else if they feel like picking up on that. I’ll say on a general note that being a global economy we have to be competitive. This doesn’t just mean on wages, we have to consider many other factors in that. I think NUMMI proved that years ago. RTW laws touch on only a fraction of the areas we need to be cognizant about.

Finally, it would be interesting to see if anyone really looked at the outcomes for the free rider. I know my company, that employs union and non union trades people across the country, have very different merit increase systems. The non union generally have more opportunity for larger raises, but the majority do not get the highest raises. I don’t know how you can quantify that, but I doubt we’re the only example where someone who is a “free rider” may make less than if they could earn merit increases on their own.

Thanks AG and appreciate your passion as well…what is the company you work for?

When I said that proponents do not offer a shred of evidence, you referenced a report which says two things you left out and ironically contradict your claim of the “benefit of larger manufacturing employment in Idaho”

1. Its not as you say, attributed to RTW, but to the decline in timber industry and possibly the lower wages, caused by RTW…but no evidence there other than anedoctal.

2. Its not a winner just because number of jobs increased. Wages and benefits declined, not just for manufacturing but spilled over into rest of Idaho economy.

Why would Wisconsin change a law, that has even the remote possibility that working class, middle class folks fall even further behind in a global economy, race to the bottom corporate mentality gripping developing nations as we speak?

Don’t even get me started on the comparisons between Idaho and Wisconsin in terms of quality of life, great schools/colleges, exciting urban livable areas, proximity to Chicago and Twin Cities, and day’s drive to over three fourths of the nation’s population, etc.

The one concept missing from the discussion is a person’s freedom to choose whether or not to belong to a union. In a non-right to work state a collective bargaining agreement can, and often does, make Union membership a condition of employment. Unions go out of their way to hide the fact that there are options to not belong but still have to pay something and they limit when someone can end their membership.

Thus, if you want a job you have to belong to an organization that may not reflect your values, priorities, or beliefs. An organization that overwhelmingly supports one political party.

If unions had a valued product or service they would not have to force people to buy it in order to keep their jobs.

Ron, under the Federal National Labor Relations Act, it is against the law to force union membership. 1985 Supreme Court case, codified that a person may resign from a union at any time. If such a contract clause were involved, the only ramification would likely be paying the exact membership costs that RTW laws wipe out; i.e. the cost of administration involved in a contract negotiation. These can be extended, complicated series of meetings, bargaining table stuff, economic data crunching, legal and constitutional matters, etc. It ain’t gonna be free…and why wouldn’t a union try to recoup those costs, given that the net result is a contract that benefits all employees not just those in the union??! Again…the analogy I use: you are in a poker game, and the pot just got bigger. You refuse to ante up…but hold onto your cards, saying that you want to win the jackpot. No one would take you seriously. Similarly: say a member of the Wisconsin Manufacturers and Commerce did not agree 100% with the political agenda of WMC. So, they withhold a portion or all of their dues. Then, they want WMC to keep providing services to them as a member. I believe WMC would respond by saying: please pay your dues, then we’ll talk services.

“An organization that overwhelmingly supports one political party.”

Which, in the case of the very powerful police and firefighter unions, is the GOP.