Evaluating The Burke and Walker Jobs Plans

Can either reverse the state’s long-term trend of lagging national job growth?

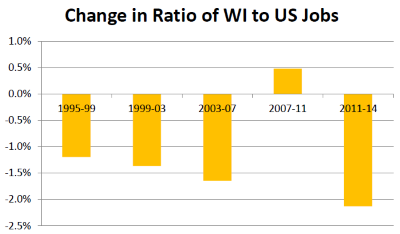

For the past twenty years, Wisconsin has experienced a gradual decline in its jobs as a share of the national job market. The accompanying chart shows the story over the five last four-year terms. The only period in which Wisconsin gained on the nation corresponds to the recession. Apparently in downturns, Wisconsin loses fewer jobs than the average state.

This trajectory is a long-term one, not attributable to any one governor. Yet the two candidates for this post both say they can improve Wisconsin’s job performance. Can they? One way to answer this is to look at the economic plans offered by each candidate and ask whether it offers the potential to move to a trajectory closer to the national average. Let’s start with Gov. Scott Walker’s plan.

His plan doesn’t directly address the question. It takes as a given that Wisconsin has already moved to a new and better trajectory than it followed under Doyle. (Its obsession with the Doyle administration is palpable, evidenced by 33 mentions of Doyle’s name. By contrast Burke is mentioned only 29 times. Burke’s plan mentions Walker three times.)

Much of Walker’s plan looks backward, either to his first four years or to what it calls the “Doyle/Burke” administration. Plans for the future consist largely of bullet points at the end of each section promising to continue the policies of the first term. Some version of the word “continue” is used 45 times, including in the title. The Journal Sentinel headlined its editorial on the Walker plan, Gov. Scott Walker’s second term? Same as the first.

To some extent this is to be expected from an incumbent. New ambitious proposals might lead to the question: if this idea is so good why did you wait until now? But it could reflect a lack of learning from the lessons of the first term.

The major policy initiative promised by Walker’s plan is more reduction in state income taxes, property taxes, and taxes on employers. It also promises to resist any attempt to roll back recently passed tax credits for manufacturing and agriculture. There is no discussion of how to pay for these reductions in revenue, particularly in light of the projected “structural deficit.”

Paying for them by expanding Act 10 to include police and fire fighters has been ruled out by Walker. The theory that reductions in taxes pay for themselves by generating more economic activity, sometimes called the Laffer curve, is rejected by most economists, but is still promoted by some on the right. It was most recently tried in Kansas, leading to large budget deficits and cuts in education and other public services. Aside from promising to root out “waste, fraud, and abuse,“ the Walker plan does not address how the budget would be brought into balance.

Underlying the Walker plan is the theory that the “job creators,” like the readers of CEO Magazine who gave Wisconsin much higher marks for business climate under Walker, are chiefly motivated by low taxes and business-friendly regulations. The evidence for this theory is hardly clear. As mentioned, it is currently being tested in Kansas and so far job growth lags even Wisconsin’s.

Many indices of business climate give points for right-to-work legislation. The Walker plan does not mention it and Walker himself has said it’s not on his agenda, but it may be enacted if Republicans keep control of the legislature. It seems unlikely that Walker would veto such legislation.

Before turning to the Burke plan, it’s worth noting the areas of agreement between the two plans, something Walker himself has noted. Shortly after Burke released her plan he told the Business Journal, “It’s interesting, actually, in that plan, it’s almost a blueprint of what we’ve been doing the last four years.”

One strategy they both support is the use of industry clusters to organize economic development efforts. Burke makes clusters the central theme of her plan, repeatedly quoting Michael Porter, the Harvard business professor credited with popularizing clusters. Walker also likes the cluster idea, while giving it somewhat less emphasis. Both plans list existing cluster organizations in Wisconsin; they become vague when it comes to describing how to encourage their growth.

Potentially, research on clusters could help answer the “nature-nurture” question—do Wisconsin’s businesses grow more slowly because they are in slow-growing clusters (such as paper) or because their Wisconsin members are less dynamic than in other states? Some years ago, the Greater Milwaukee Committee hired Porter to introduce the concept to Milwaukee businesses, but it has since moved on to other efforts, suggesting an effective cluster strategy might not be easy.

Both plans also lay out increased efforts to encourage entrepreneurship by expanding available capital and encouraging incubators for new ventures, although Burke criticizes Walker for underfunding these programs. Burke does promise to veto any legislation giving state money to “state-certified capital companies” or CAPCO’s, which Walker proposed early in his first term, but is unmentioned in his current plan.

Both plans promise an expansion of training and apprenticeship programs. They promise to keep UW tuition affordable, Walker by continuing the UW tuition freeze, Burke offering tuition tax credits.

In other areas there are sharp differences. Noting that Wisconsin gets back only 86 cents for every dollar it sends to Washington, Burke promises to aggressively pursue federal dollars, criticizing Walker for turning down federal funding for Medicaid expansion, broadband in schools and high-speed rail. Walker’s plan does not mention federal funding other than celebrating that Wisconsin was put on the short list for a federal grant for innovative manufacturing. It does, however, promise to “Increase efforts to fight back against unnecessary and burdensome federal regulations that are increasingly a threat to Wisconsin jobs and economic growth,” without offering examples of such regulations.

Burke proposes raising the minimum wage, something Walker’s plan doesn’t mention. Walker himself has opposed it, generally by saying he wants to get more high-wage jobs.

Burke advocates opening the state’s venture fund to biotechnology investments and allowing stem cell research, topics not mentioned in the Walker plan.

The two plans show a sharp disagreement in how to “grow our rural economies,” (in the words of the Burke plan). Burke emphasizes expanding the market through efforts like encouraging organic farming and consumption of local production. By endorsing goals for increased total milk production, Walker’s plan backs the trend to larger, more concentrated farms.

Both plans lack a strong urban quality of life vision. As Greg Ballard, the Republican mayor of Indianapolis noted to Governing Magazine, “the city lifestyle is increasingly attractive to more and more people,” but this requires a focus on “bike lanes, trails, sustainability, and the artistic, cultural and sports components sought by urban dwellers. These are areas in which Republicans are traditionally weak.”

One study traced the career path of successful entrepreneurs and the reasons they picked a particular location for their business. Typically after college they found employment in a location that offered an attractive lifestyle. After a decade or two of working for someone else they started a business where they earlier decided they wanted to live. When asked to list the most important considerations in a location, lifestyle came first and the ability to attract employees second. Purely financial considerations such as taxes came near the bottom.

The Walker plan does not mention lifestyle. Presumably this reflects a belief that offering an attractive lifestyle, while desirable for its own sake, does not attract jobs.

We need nearly 670,000 more degreed workers in Wisconsin over the next dozen years to meet projected employer needs. We’re not going to meet that objective if the bright minds we send to our universities and technical colleges then leave our state because they can’t find the career opportunities – or quality of life – they seek.

In two sections she talks of stopping the brain drain by investing in quality of life, but limits her examples to marriage equality, broadband, transportation, and arts and culture. Perhaps fearing that she will be typecast as the candidate of Madison and Milwaukee, she forgoes the opportunity to set forth an urban policy to help make Wisconsin cities magnets for those seeking the advantages of an urban lifestyle. Neither plan has a vision of how to turn Milwaukee into a Portland, or Madison into a Boulder, nor how to assure a future for Wisconsin’s smaller communities if their anchor industries leave.

Both campaigns have misused data during the run-up to the election, keeping fact checkers busy. This shows up in their plans, although the Walker plan has far more examples, perhaps reflecting that it was issued at the height of the campaign. Data abuse tends to take one of several forms:

- Ignoring the recession. The Walker plan says, “After losing more than 133,000 jobs in Governor Doyle’s final term, Wisconsin has created more than 100,000 private sector jobs thus far in Governor Walker’s term.” In the same spirit, Burke’s plan compares the unemployment rate when she was Commerce Secretary to that today, again ignoring the national context.

- Ignoring data scatter. Both candidates selectively pick time periods aimed at making their point.

- Using obscure, unproven data. For example, Walker’s plan claims, “Wisconsin rate of job growth performed better than any state in August according to a national index reporting on the 20 most populous states.” This claim, based on a report from a payroll processing firm, is technically true but probably reflects sampling error.

Assuming she follows through as governor, Burke’s plan offers relief from data abuse. It promises an online Wisconsin Jobs Dashboard, showing a number of metrics reflecting the state’s progress in meeting her goals. Consistent reporting of data would be a big improvement over the cherry-picking of data series and time periods that is typical of the current administration.

Data Wonk

-

Life Expectancy in Wisconsin vs. Other States

Dec 10th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Dec 10th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

-

How Republicans Opened the Door To Redistricting

Nov 26th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Nov 26th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

-

The Connection Between Life Expectancy, Poverty and Partisanship

Nov 21st, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Nov 21st, 2025 by Bruce Thompson