Which Governor is Best At Growing Jobs?

The truth is far more complicated than either party would claim.

Because Gov. Scott Walker promised to bring 250,000 new private sector jobs to Wisconsin, there has been considerable attention to his record, and to that of his Democratic predecessor, Gov. Jim Doyle. Walker, for instance, has made comparisons suggesting the economy did very poorly under Doyle. It is useful, therefore, to take a look at the record.

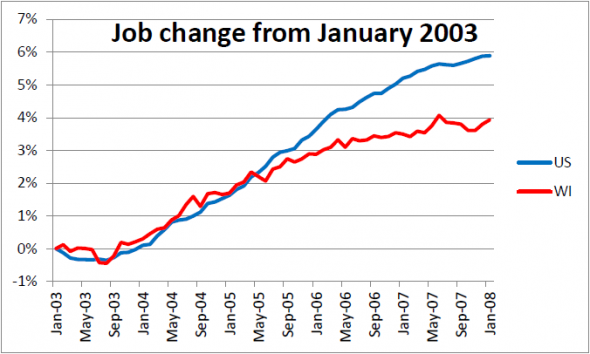

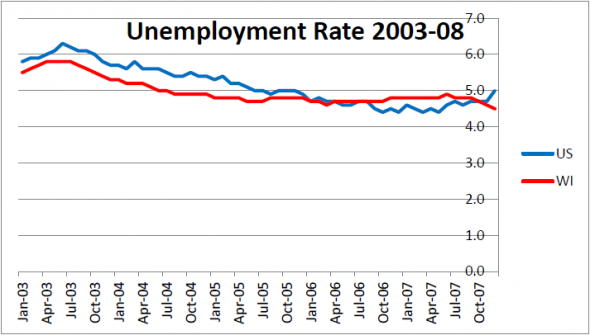

At times Doyle did worse and at other times better than the nation did in growing jobs. Take the period from January 2003, when Doyle took office, to early 2008. As shown below, Doyle entered office at the end of a mild recession. During his first two years employment growth in Wisconsin closely tracked national employment, but later fell behind.

Both the national unemployment rate and Wisconsin’s dropped during this period, though the national rate was at times higher and at other times lower than Wisconsin’s unemployment rate.

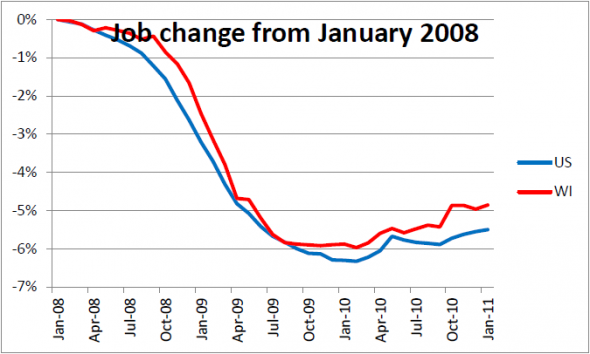

In January 2008, jobs hit a peak both nationally and in Wisconsin, and then turned down, soon dropping drastically. They hit bottom by early 2010 and then started a slow recovery. Wisconsin fared somewhat better than the nation during this period. Its job loss came later and was slightly smaller than if it simply followed the national average. And its recovery slightly exceeded the national average.

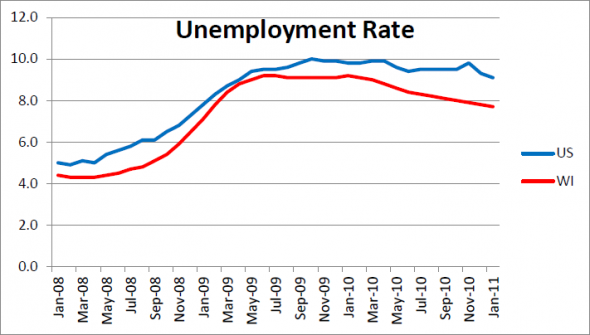

The difference in job losses was reflected in unemployment rates. At its worst, Wisconsin’s unemployment dropped to 9.2 percent, compared to 10 percent nationally. By the start of 2011, the state’s unemployment dropped from 9.2 percent to 7.7 percent, well below the national average of 9.1 percent.

In comparing state and national job trends, it is striking how similar their shapes are. When the national economy is booming, Wisconsin adds jobs. When it falters, Wisconsin sheds jobs. Still there are differences. Should Doyle be blamed for the smaller job growth between 2005 and 2008? If so, should he then get credit for the better performance in Wisconsin once the recession hit? To answer these questions, it is useful to ask whether there were economic trends that might have had a disproportionate effect on Wisconsin.

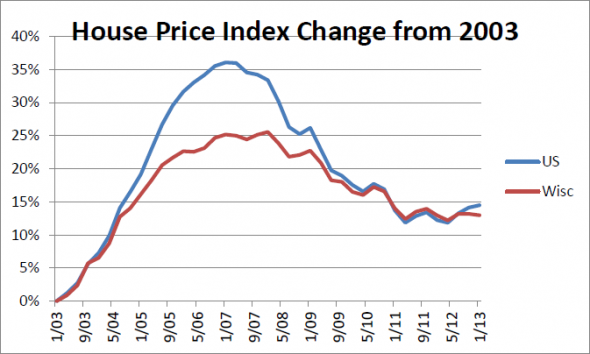

One candidate is the housing bubble. A number of studies have found that when the value of their homes increase, people feel richer and spend more. Wisconsin had its own housing bubble, but its peak was lower than the average nationally. In fact, during the period that Wisconsin’s house prices lagged behind national growth rates so did its job growth. Lower growth in home values in Wisconsin could be expected to result in lower spending growth, resulting in turn in lower job growth.

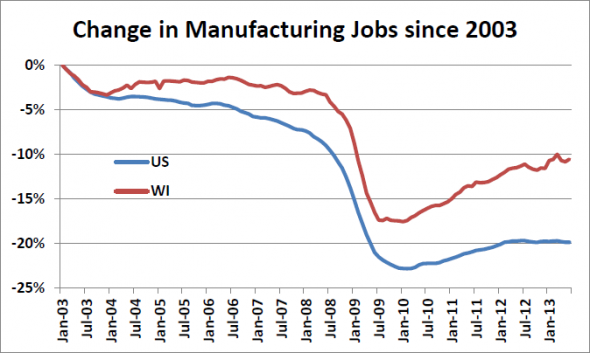

A second trend which may effect job growth in Wisconsin is the relative growth of manufacturing jobs. With a fifth of its jobs in manufacturing, a decline in manufacturing would hit Wisconsin harder. Even so, Wisconsin’s manufacturing jobs seem to have survived better than in the 49 other states, as the graph below shows, and, once the bottom was hit here, manufacturing recovered more quickly than was true nationally. (An interesting side question is why Wisconsin’s manufacturing jobs declined less as a percentage than the national average.)

Studies by political scientist Larry Bartels and his colleagues have found that voters reward incumbents when times are good and punish them when things turn sour even when the causes are clearly beyond the incumbent’s control. For example, one study of European elections in the Great Recession found that countries with conservative governments elected parties to the left and those with socialist governments elected conservatives. A study of US elections found that incumbent governors in energy-producing states were more likely to be re-elected when oil prices were high than when prices were low. A similar pattern was found in Midwest states with heavy manufacturing: when manufacturing prospered, incumbents were re-elected, but they were likely to lose when it shrank.

Trying to separate outside factors from those under the control of an incumbent governor is difficult enough under the best of circumstances. But often commentators start with a conclusion and cherry-pick data for evidence that supports that conclusion. Sometimes their motivation is political and sometimes ideological.

-

As an example of a political motive, consider this quote from Governor Walker’s web site: “When Governor Walker took office, Wisconsin had lost nearly 150,000 jobs in the previous three years and, at the low point, unemployment topped 9 percent. ….. Today, the unemployment rate has dropped to 6.6 percent.” This represents a combination of blaming his predecessor for bad news while taking credit for good things that actually happened under his predecessor. Not noted is that the job loss during this three-year period was less than what would have been expected if Wisconsin had followed the national pattern, or that most of the decline from 9% to 6.7% unemployment (not 6.6%) actually happened before Walker took office.

-

As to an ideological motive, consider the lists that several organizations publish ranking states’ by their purported business-friendliness. The lists often widely disagree as to which states are most business friendly, but typically reflect the beliefs of the sponsoring organization. For example, one widely publicized list, that published by CEO Magazine, reflects the view of the magazine and its readers that friendly states have right-to-work laws and elect Republican governors and unfriendly states raise their minimum wage, require sick leave, establish health care exchanges, and raise taxes. All in all, the rankings do a very poor job of predicting which states will have high job growth or low unemployment rates when put to the statistical test.

In reality, we do not fully understand why some states prosper and others struggle or why their relative economic positions often change over time. Yet there is no shortage of advocates of one or another policy eager to selectively interpret the results to their advantage. At a minimum it is wise to recognize that states are heavily influenced by national economic trends, and that state government policy is only one factor of many influencing a state’s economic success.

Data Wonk

-

Life Expectancy in Wisconsin vs. Other States

Dec 10th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Dec 10th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

-

How Republicans Opened the Door To Redistricting

Nov 26th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Nov 26th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

-

The Connection Between Life Expectancy, Poverty and Partisanship

Nov 21st, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Nov 21st, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Why do some state prosper while others do not? Compare Texas to wisconsin from 2000 to 2010, their polices and their growth. Even if you remove the oil, the atmosphere is just different, that is why KC went down there.

Missing in all of this ‘analysis’ is the quality of jobs. A hundred thousand ‘would you like fries with that ?” jobs is easily counter-balanced by 10 thousand high-tech jobs. That point has been lost on both Democrats and Republicans and media analysts.

While Mr. Walker is fast to blame his predecessor, the Greeks, and teachers rather than the Wall Street Banksters for the tough times, the fact remains during the past two years of the Obama recovery, Minnesota’s per capita annual income has doubled to $12 thousand higher than Wisconsin’s.

Minnesota has high-tech, and Wisconsin doesn’t.

The Walker formula of borrowing, to give cash to his rich donors is a most unlikely solution to the longer-term problem of our state falling further behind as it ‘moves forward’. Something Walker is counting on from media ‘analysts’ who produce graphs that really don’t say anything of value.

Doubled? Wow, that’s incredible! Though, I’m having trouble finding anything to support that. It looks like it went up 3.7% from 2011 to 2012 ( http://blogs.mprnews.org/minnecon/2013/04/mn-per-capita-income-growth-outpaces-us/ ), which means that you’re claiming it has gone up another 96% from 2012 to 2013 ( “the fact remains during the past two years of the Obama recovery, Minnesota’s per capita annual income has doubled” – Rich Fallis ). I would love to see more stories on this incredible growth in Minnesota. Please, any information you have would benefit us all.

Kyle,

My guess is that Rich was talking about double growth rather than double income. Since the start of 2011, Wisconsin’s job growth has been a little over half of Minnesota’s.