Milwaukee’s Time of Terror

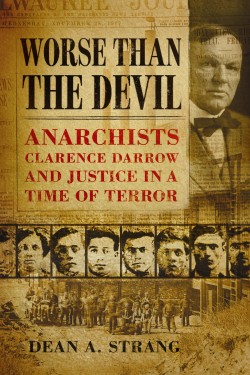

A new book recounts the police station bombing of 1917, and Clarence Darrow’s defense of the anarchists charged with the crime.

Worse Than The Devil: Anarchists, Clarence Darrow And Justice In A Time of Terror.

Detective Fred W. Kaiser’s watch stopped at 7:43 on Saturday evening, November 24, 1917. The bomb, loaded with screws, bolts, and other metal odds and ends intended specifically to kill, cost him his life in the same tick of the second hand. Nine other lives stopped just about that abruptly, too.

With a blinding flash, every window in Milwaukee’s central police station on the Oneida Street side erupted onto the street in a jagged shower. The clap was so loud that those in the building who survived felt more than heard it. The momentary spike in air pressure deafened them temporarily and blackened their vision for a few seconds. In the squad room, the violently expanding air at incinerating temperature had already completed its work and escaped through the ragged holes and gaps it had torn everywhere. Lights went out, pitch black dropping instantly in the building.

In his office, the blast threw Lieutenant Robert Flood from his chair and left him stunned. He staggered to the squad room across the entrance hall as soon as he could walk. On the street, smoke and plaster dust belched out the gaping window holes. Acrid smoke and dust and burnt fiber and flesh gagged those who still breathed. To the men inside who could hear only the ringing in their ears, the others who staggered or ran pell-mell with their mouths going furiously appeared like actors in an insane pantomime. Detective Bert Stout, not halfway across the street as he walked diagonally west toward the Pabst Theater, turned around to rush back in. Within minutes, firemen from the neighboring Broadway Engine House began a search by lantern light.

Detective Charles Seehawer and Detective Stephen H. Stecker had started together on the police force the same day, December 1, 1899, and were wounded mortally while just shoulders’ width apart. Stecker landed near the doorway. “His arms and limbs were crushed to pulp and his body was mangled frightfully,” the Milwaukee Sentinel reported. Kaiser, whose stopped watch froze the moment, was dead. Spindler was in his death throes; next to him upstairs, other telephone operators were unhurt. Detective David G. O’Brien, the most experienced officer in the room and possessed of a splendid, thick mustache, died face down in the center of the room. Not three weeks earlier, he had celebrated twenty years of service. Detective Albert H. Templin and Detective Paul J. Weiler perished. They had been together two months earlier during the Bay View riot, three miles south of the police station, on September 9. Templin had been shot that day, but his wound was minor and he had missed perhaps not a full day’s work. The pieces of Detective Weiler’s revolver were twisted out of shape, its barrel lost altogether. The young plainclothesman Frank M. Caswin was lost, too.

And one civilian, Catherine Walker, who evidently had been just to the side of the open squad room door in the entrance way, would not make it. A few seconds more and she would have escaped unscathed. Instead, she was “beyond human aid.” She lay among most of the corpses, which were “piled in crushed heaps on the floor.” The coroner’s gray ambulance took the dead to the county morgue.

So Saturday ended.

In the weeks before, autumn had blanched to gray, soon to be white. A bleak Thanksgiving approached. The city had awakened to life in a minor key that Saturday morning. An icy wind gusted out of the northwest and the temperature would rise no higher than 36 degrees.1 Milwaukee, huddled on the western shore of Lake Michigan around the mouth of the Milwaukee River, had turned inward for the winter. Ninety miles of farmland, stark after harvest, separated it from Chicago, with the industrial patches of Racine, Kenosha, and Waukegan lying between. In morning’s low sun and again backlit at dusk, Milwaukee’s irregular profile against the sky at first appeared all spikes of smokestacks and church spires, similar in that light. Below, on closer inspection, orderly gray sawtoothed rooftops of bungalows and workmen’s cottages separated stack from steeple. Here and there, smoke arose, in meandering wisps from home furnaces and in purposeful dark plumes above factories. In the foundries, shutting down the furnaces would mean replacing the ceramic linings, so the fires burnt constantly.

Closer still, commercial buildings and more substantial homes built of Milwaukee’s distinctive “cream city” brick lightened the grays of the city’s clap-boards. Eventually, though, soot of coal and coke darkened all to smudge and black. That same soot tinged the cheaper russet brick of the city’s warehouses. At street level, trolleys of the Milwaukee Electric Road & Light Company plied cobbled streets webbed overhead in black wiring. Ornate street clocks stood sentinel at intervals between dingy street lamp posts. Leafless trees lined the streets, their branches spreading outward into the diffuse gray.

Winding down from the farms of Cedarburg and Thiensville several miles north of the city and gathering width as streams and creeks fed it, the Milwaukee River was muddy gray and smooth. It coursed southward and then bent east in the Third Ward, just south of downtown, to pour with the Menominee and Kinnickinnic Rivers from the west and southwest into steely cold, choppy Lake Michigan. Steamships and mercantile vessels were fewer on the river as the time of ice approached and the Great Lakes became too treacherous for trade. That morning the ships remaining sat listlessly at mooring.

Few of Milwaukee’s Germans, Poles, Italians, and Irish, who mostly had drifted northward from Chicago in search of work, found reason to test the raw air outdoors on a Saturday morning in late November unless they had to work. Neither did the blacks who had clustered just north and west of downtown after migrating from rural Arkansas and Mississippi and Alabama for industrial work. Working men and women stayed indoors if they could.

Electric lights burned even at that hour, to banish November’s gloom. Men smoked and read the morning Milwaukee Sentinel, the florid daily that was the city’s oldest newspaper, dating to 1837, eleven years before statehood. The speculation of the day was that the New York Giants might trade their second baseman, Charley “Buck” Herzog, back to the Reds (they did not; he went to the Boston Braves). Other men, women, and children puttered at their respective chores. Families played sheepshead, Schafkopf in its original German, the local card game with a thirty-two-card deck, around kitchen tables with extra chairs pulled close for nearby aunts and grandmothers and cousins. They busied themselves with early preparations for the coming Thanksgiving meal. Still, just as nature wore Wisconsin’s washed grays of winter, the city’s mood had a tint of tension.

Not because it was November, though, and surely not because it was Saturday, but because it was 1917 and the war was on. At least superficially, most Milwaukeeans supported the war and President Wilson. Good people made a show of the flag- bunted politics that they thought appropriate in wartime. Patriotism generally won public praise. Just eleven days earlier, November 13, the war had claimed its first Milwaukeean, a Polish immigrant. Six days before that, the Bolsheviks had seized power in Russia. The red scare loomed. Yet this also was a city with a history of electing a Socialist Party mayor, district attorney, and city officials. It was Victor L. Berger’s city: he the stoutly sincere socialist editor of the Milwaukee Leader and a founder of the Social Democratic Party in 1900. That party merged with the Social Labor Party in 1901 to become the Socialist Party of America. Although never a firebrand, Berger in little more than a year would be both a re-elected U.S. congressman whom Congress would refuse to seat and an Espionage Act convict serving a twenty-year sentence for disloyalty. He and his intellectually imposing wife, Meta Berger, pled the case for pacifism in print, in speeches, and in meeting halls. They pled it in English. They pled it in German, which both spoke: Victor was an Austro-Hungarian Jew by birth. Seven weeks earlier, the postmaster general had revoked the second-class postage permit of the Milwaukee Leader in an effort to silence Berger. The disloyalty indictment would follow the next year.

Milwaukee was a city of fresh immigrants. From 1890 through 1908, of the twenty-eight leading cities in the United States, Milwaukee had the largest population with foreign-born parents. A staggering 82.7 percent of the city’s people in 1908 had parents born abroad. The largest group by far was German. Many in that group were torn between pride in the young nation to which they or their parents had immigrated and the ancestral tug of the kaiser’s Germany. A substantial Austro-Hungarian population faced the same internal torment of crossed allegiances. The next largest immigrant group, Poles, perhaps had not the same ancestral conflict.

“Milwaukee’s Germans, Poles, Italians, and Irish … mostly had drifted northward from Chicago in search of work.”

Really? I’ve never read anywhere that Milwaukee owed its population growth to Chicago drifters.

Did the author of the book also write the article about the book? Wow, journalistic ethics strike again.

@John… It is an excerpt from the book, which it says at the end of the post.

Good job to read the whole post there John…

So laziness not unethical. Got it.

Too lazy to read the entire article?