How Sand Mines Pollute

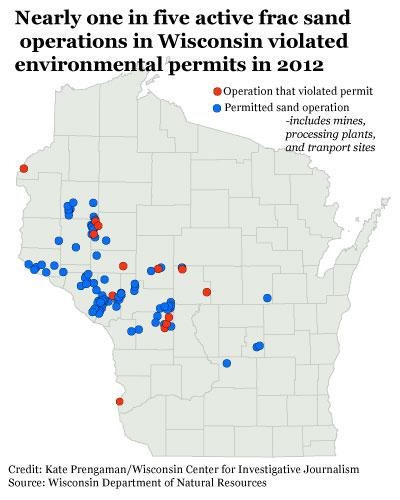

Wisconsin is the leading supplier of sand for oil and gas fracking. But nearly one-fifth of sand mines have environmental violations.

An overview of the 400 acre plot of Preferred Sands mine in Blair, WI, on June 20, 2012. The Wisconsin Department of Justice is reviewing Preferred Sands for environmental permit violations during the spring of 2012 Lukas Keapproth/Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism

Wisconsin’s Sand Rush

Studying the impacts of the sand industry

Competing studies are under way to assess air pollution from Wisconsin’s frac sand industry, and the author of one said current state law isn’t protecting people well enough. A separate study, meanwhile, will examine the impact of frac sand mines on water. Read more here.

How to report a concern to DNR

Tips from residents alerted the Department of Natural Resources to several frac sand mining environmental violations. The DNR encourages people to report suspected environmental, wildlife, or recreational violations. You can make a confidential report by calling 1-800-TIP-WDNR (1-800-847-9367), or emailing le.hotline@wisconsin.gov

Deb Dix, an environmental enforcement officer, said that the most useful reports included specific location information and as much information as possible to aid the staff who follow up on concerns. Although you can leave an anonymous report, Dix said that it can help if tipsters leave a call-back number, for follow-up.

Sand mining regulations

Frac sand mines and processing plants need permits from the state and local governments. Read the list here.

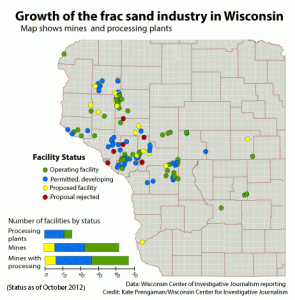

Interactive Map

View locations of sand deposits and frac sand mining and processing operations. Click the image below to open a larger version.

Nearly a fifth of Wisconsin’s 70 active frac sand mines and processing plants were cited for environmental violations last year, as the industry continued to expand at a rapid clip.

Violations included air pollution, starting construction without permits, and an accident at the Preferred Sands mine in Trempealeau County where a mudslide during a heavy rainstorm damaged a neighboring property.

In addition, the state Department of Natural Resources cranked out letters of noncompliance — warnings to fix a problem before it becomes serious enough to merit a notice of violation — at numerous facilities.

“Some of these companies should have known better,” said Marty Sellers, a DNR air management engineer.

“They seem to put construction and production ahead of regulations.”

Usually, Sellers said, the DNR expects 90 percent of companies in a regulated industry to comply with rules on their own. But in his visits to a dozen frac sand facilities, Sellers encountered the opposite pattern, and he sent letters of noncompliance to 80 to 90 percent of the sites.

DNR compliance officials acknowledged they have been stretched thin monitoring the sand industry, which has grown from a handful of sites five years ago to more than 100 permitted mining, processing or transport facilities today.

Wisconsin is the nation’s leading supplier of frac sand. The companies mine, sort and wash sand for use in hydraulic fracturing of shale to extract natural gas in other states.

Gov. Scott Walker has proposed two new DNR positions in his budget to monitor the sand industry, by shifting $223,000 from other parts of the budget.

The Wisconsin Industrial Sand Association, an industry trade group representing five large companies, applauded the move. Increasing staff will help to ensure that all mining companies operate according to state laws, the group said in a press release.

Citizens aided enforcement

Dust generated the most community complaints about frac sand operations in 2012, but most violations involved stormwater permits.

DNR environmental enforcement specialist Deb Dix said some of the violations resulted from residents’ complaints. Perhaps because sand mines have provoked so much controversy, citizens have been alert to problems, Dix said — more alert than for similar problems that can be caused by road work or other construction.

In response to complaints in the Frac Sand Sentinel, an e-newsletter for anti-mining activists, that the DNR was slow in responding to a runoff concern, a DNR stormwater specialist wrote in, explaining that the extra vigilance was helpful.

“I do greatly appreciate any and all photos and reports,” Ruth King wrote. “It is precisely because I am only a half-time employee and cannot be everywhere at all times that we really really need concerned citizens to be our eyes and ears.”

In neighboring Minnesota, where Democrats are in control of the legislature and governor’s office, a Senate committee approved a bill on Tuesday calling for a statewide moratorium on new mine development and a study of the industry’s environmental impacts.

But in Wisconsin, where Republicans are in control, the DNR decided last year that existing non-metallic mining regulations were sufficient to handle the frac sand boom, and politicians appear unlikely to move toward more regulation.

Shirley Evans of Modena, in Buffalo County, Wis., protests frac sand mining outside a sand industry conference in Minneapolis on Monday. Citizens concerned about the environmental impact of the mining industry have been reporting suspected violations to the DNR. Kate Golden/Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism

The proposed two new DNR positions would most likely be focused on mines’ compliance with air quality regulations, said Tom Woletz, the DNR’s point person for frac sand.

“Many Wisconsinites have the impression of the DNR as a big strong agency, but it’s not what it was 10 years ago,” said Pilar Gerasimo, a journalist and environmental activist in Dunn County. “They are understaffed and have not been able to keep up.”

Gerasimo said that she worries that under the Walker administration, the DNR is doing more to “work with” businesses that are potential polluters and spending less time tracking potential problems.

Air regulator Sellers said he only inspects large operations that dry sand, a process that poses the greatest risk of dust pollution, on a rotating basis and when mines are testing emissions for permitting purposes. The air quality compliance staff doesn’t inspect small mines regularly unless someone complains about them.

Two significant runoff incidents

The DNR referred two May 2012 frac sand mine violations that caused significant environmental damage to the Wisconsin Department of Justice. The agency said it is reviewing the cases.

At the Preferred Sands mine in Trempealeau County, the mudslide that flooded a neighbor’s property during a heavy storm violated its stormwater permit. The Minnesota-based mining company also had multiple violations of its air quality permit.

Todd Murchison, the Preferred Sands regional manager, has said that the company had learned a lot from the accident, changed its policies and was cooperating with the DNR.

At the Burnett County mine owned by Minnesota-based Interstate Energy Partners, a leak in a holding pond let silt-laden water leak into the St. Croix River for a few days before it was noticed by a hiker.

“A release like that could have been devastating to wetlands or the St. Croix if left uncorrected,” Dix said about the leak. “The regulations are there to protect the environment — from catastrophic events and ongoing damage.”

“A release like that could have been devastating to wetlands or the St. Croix if left uncorrected,” Dix said about the leak. “The regulations are there to protect the environment — from catastrophic events and ongoing damage.”

Three additional companies were fined in 2012.

Last March, the DNR received a complaint about muddy water in a stream and found a leaking holding pond at the Panther Creek Sand mine in Clark County. According to Dix, the damage was minor and the company fixed it right away; it was fined $464.

Bear Creek Cranberry in Monroe County paid $868 for serious problems with its environmental protection plan.

The Chippewa Sand Company notified county officials in April that a pond holding wastewater overflowed into a drainage area, eventually soaking into the soil. Dan Masterpole, the Chippewa County conservationist, said the company was fined $2,795 and made changes to prevent similar problems in the future.

Runoff problems are more likely in the spring as snow melts and mines resume operations, Masterpole said, so Chippewa County has scheduled inspections for this spring.

Nine companies that received violations faced no fines, Dix said. Their violations were largely either paperwork problems or other easily corrected issues.

Few air pollution violations so far

Dust pollution — a potential health concern as well as a nuisance — attracted the most attention from citizens, but only a few sand mines received serious air quality violations.

Companies monitor dust levels to protect workers. They spray water on exposed soil and use specialized equipment like dust collectors and covered conveyors to prevent pollution, Woletz said.

Trouble occurs if that equipment fails.

That’s what happened at the Pattison Sand transport facility in Prairie du Chien. Sellers received lots of calls about dust coming from the portable system used to load sand from trucks to train cars.

Between his busy schedule and the fact that the portable facility comes and goes, it was almost a year before Sellers observed the operation in action. The callers were correct: He saw dust escaping from the area where the truck unloaded sand.

He also noted a problem that day with the conveyor loading to the railcar. Sellers watched the operator try to fix the seal without success, and then continue to transfer the sand.

He wrote Pattison Sand, an Iowa-based company, a letter of noncompliance, warning it to fix the problem and improve its dust prevention protocols or face fines.

‘Growing pains’ of new industry?

However, Sellers said he has also seen problems from experienced companies.

He wrote Connecticut-based Unimin a letter of noncompliance for starting construction at its Tunnel City mine without proper permits. And neighbors of the U.S. Silica mine in Sparta alerted him of dust problems during construction work by the Maryland-based company.

Resident Gerasimo said the laws aren’t tough enough on mining companies who take a lax approach to environmental protection.

“For frac-sand mining interests, the risks of being held accountable are low and temporary. The fines are meaningless in relation to both the potential profits and damages in question,” Gerasimo said. “Two new agents isn’t going to change that.”

DNR’s Dix, however, said the agency expects to see fewer violations in the future.

“Sometimes, it’s just the growing pains of an industry,” Dix said. “Usually, once we catch them, they get it corrected, and we’re done.”

Interactive map of frac sand operations that received violations

The nonprofit Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism (www.WisconsinWatch.org) collaborates with Wisconsin Public Radio, Wisconsin Public Television, other news media and the UW-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. This story was a produced in collaboration with Wisconsin Public Television.

All works created, published, posted or disseminated by the Center do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.

-

Legislators Agree on Postpartum Medicaid Expansion

Jan 22nd, 2025 by Hallie Claflin

Jan 22nd, 2025 by Hallie Claflin

-

Inferior Care Feared As Counties Privatize Nursing Homes

Dec 15th, 2024 by Addie Costello

Dec 15th, 2024 by Addie Costello

-

Wisconsin Lacks Clear System for Tracking Police Caught Lying

May 9th, 2024 by Jacob Resneck

May 9th, 2024 by Jacob Resneck

Here is another example of how you convince people that the government is the problem. You don’t enforcement so that the system dosen’t work.