A part of the solution

photos by Scott Winklebleck

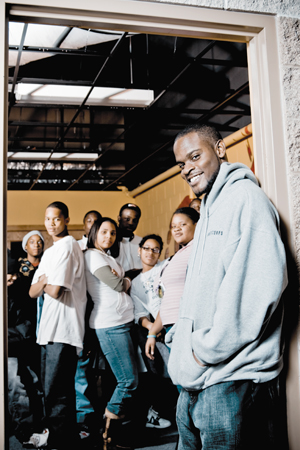

In the auditorium of the John C. Cudahy YMCA, the basketball hoop blocks the view of the stage. Kendall tells the lanky teens shooting hoops to go upstairs for a while so Scott can set up his tripods, flashes and umbrellas.

This is the only YMCA in the country built specifically to accommodate the arts. Set on 55 acres of wooded land – formerly John C. Cudahy’s farmstead – and home to a “safe place” where teens can study, use computers and play sports and video games, it’s a far cry from the popular image of the Y as a fitness club, a place to play racquetball and run laps on the track.

Kendall Hayes, now 20, joined AmeriCorps right out of high school. He’d been working so many hours at the branch’s front desk as part of STEP-UP (a career development program for high school students run by the county’s Private Industry Council) that a friend suggested he might as well earn volunteer hours and collect an education award as a full-fledged AmeriCorps member.

Now he’s in his second year of service at the YMCA, where he helps students in the teen program with everything from homework and test preparation to setting up bank accounts and working creatively.

“[I try] to get kids to stay active, to get them to expand their horizons and open them up to new things,” he says, “not just coming here to play basketball every day, but getting them to do something artsy, or getting them to go back and help their community.”

Right now, Kendall is working on developing an art guild for the teens that would incorporate creative writing, music and visual art. AmeriCorps members can serve a maximum of two terms and qualify for the education award, and when his term is up, Kendall plans to go to the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, maybe to study recording arts and psychology.

“I’m the type of person that likes to do everything, [and] AmeriCorps has offered new possibilities for me … We’ve [done everything from] helping inner city youth to working on Philadelphia Community Farm to disaster relief training,” he says. “[But] going back to school is a whole different section of my life.”

Still, he says, “I do wish that I could stay longer. There’re a lot of different opportunities and I don’t feel that I’ve experienced it all. And I’m always willing to lend a helping hand.”

Kendall’s commitment to public service is unadorned, stunningly simple. In our interview, he speaks gracefully about what service can do for communities – and what community service gives to those who serve.

The organization

In 1993, then-President Bill Clinton established AmeriCorps as the country’s flagship service initiative. It’s often assumed to be a single program, like the domestic version of the PeaceCorps, but AmeriCorps is actually a network of organizations, a bear hug that encompasses four primary programs: AmeriCorps*State and AmeriCorps*National, which provide funding and volunteer resources to statewide and national organizations; the National Civilian Community Corps, a residential program not unlike a public service “army,” whose members are trained and then regionally dispatched to help with urgent needs like disaster relief, education and the building and rehabilitation of low-income housing; and AmeriCorps*VISTA (Volunteers in Service To America), whose volunteers work in administrative, programmatic and capacity-building roles. VISTA has been around since the ‘60s, but was built into AmeriCorps at its inception.

Since then, almost a half-million people have served. AmeriCorps members tend to be younger, in their teens and twenties, although people of all ages are welcome to participate (and do). Members sign on for at least a full year of service and may complete up to two year-long terms; while they are volunteering they receive a modest living stipend, and when their term of service is complete, they are granted an education award that may be used to pay back qualified loans or fund further study.

The range of things AmeriCorps members do for the city and the state is vast – and yet they work under the radar, almost invisibly, like you’d never know they’d been there unless you asked. They build and winterize houses and reach out to youth on the street. They teach kids to read and they educate undeserved communities about health resources and social services. Some work at camps and farms; some clean up rivers and trails; others work at desks as administrators and researchers in nonprofit institutions. And hopefully, every year or two, a fresh corps of engaged, active, empowered citizens go into the workforce, the academy and the community as life-long advocates of service and believers in positive change.

The secret

“AmeriCorps is one of the USA’s best-kept secrets,” says Pat Marcus. She runs the SPARK Early Literacy program at the Boys and Girls Club of Greater Milwaukee, where 50 part-time AmeriCorps members serve at six different sites. SPARK – Spheres of Proud Achievement in Reading for Kids – works with children from kindergarten through third grade to engage them in literacy activities in every “sphere” of their life – their schools, their families and their communities. With their tutors – all AmeriCorps members – kids in SPARK read books, play games, make crafts and put on plays. SPARK tutors put together family book bags with books to borrow and keep, puzzles, stickers, snacks and pencils, and write letters to their kids and send them home with a self-addressed stamped envelope and a prompt.

“I’m a big believer that we all learn on a need-to-know basis,” Marcus says. “And if you get a letter in the mail, you’re going to try and read it … All of the kids are struggling readers and writers, so to just say ‘write a letter back’ is not very helpful, but if you say ‘draw a picture of everyone in your family, and write their names on it,’ that’s still writing.”

Critics of AmeriCorps like Libertarian watchdog James Bovard have scandalized the tutoring sessions that go on in many programs like SPARK, charging that “puppet shows” are hardly productive experiences for children in challenged circumstances.

But early literacy is a complicated gambit.

“There are so many techniques,” Marcus says. “People get doctorate degrees in early literacy.” That’s why it’s so important that SPARK tutors are appropriately trained – and that program directors can use grant money as it suits them.

“The real beauty of AmeriCorps is that it’s not federal dollars being imposed on cities and communities; it’s communities saying ‘This is what our need is; this is what we think we can do with the money,” says Marcus. “A lot of federal programs come in and say, ‘This is the model; follow what we say.”

She does struggle with the two-year service term limit, which poses difficulties both in terms of growing the program and in developing relationships between tutors and students.

“It is a challenge. We’re talking about kids, so to walk in and out of a kid’s life … these bonds happen instantly. I had a potential tutor ask me how you form bonds with the kids. [But] you don’t have to do anything. The kids love the attention. They have an adult fully [focused] on them for 30 minutes at a time, three days a week.”

As the program grows, Marcus admits that she will probably move beyond using AmeriCorps members exclusively, which will involve changing the model of the SPARK program somewhat to include longer-serving tutors and more bilingual volunteers. For now, though, her tutors – many of whom are preservice teachers – have their hands on the pulse of early education, and a hand in thesupport and success of kids who might otherwise slip through the system.

Beyond numbers

At the YMCA, AmeriCorps funding has allowed its programs to “reach populations that our normal YMCA services couldn’t,” says Casey Renn, AmeriCorps Specialist for the YMCA of Metro Milwaukee.

“Young people today have been products of white flight and urban sprawl,” says Renn, a young man himself. “We don’t want to live like that anymore. We want to walk down the street and go to the grocery store and have a sidewalk. That’s not too much to ask. I think that’s why AmeriCorps is engaging more people than ever before.”

It’s a bright November afternoon at the Downtown YMCA, and we’re having an impromptu panel discussion as four AmeriCorps members placed with the Y in different capacities discuss why they serve, what challenges them and what inspires them to keep working. And while it’s true that a term of service takes commitment and fortitude, no one wanted to qualify their position as anything but a regular job, and many found the richness of their experiences and the rewards of serving as agents of transformation overshadowed the sacrifices.

Rob Topinka joined Public Allies, a leadership training program, this fall after graduating from college in the spring of 2007. When he found out he had been accepted to the program, he called his mom to ask her advice.

“I had another job offer at the same time, and it paid a lot more – and she was kind of hinting that I should take it. She called me back in five minutes and said, ‘Forget everything I just said, I sounded just like my mom.’ I think my dad’s jealous – he always wanted to work with kids, he always wanted to be a teacher. And they think it’s a real job. Because it is.”

“I come from a small community, so working in Milwaukee – my parents are really concerned,” says Ali Henderson, who serves in the Y’s One-on-One mentoring program. “My grandma calls and asks if I’ve been shot yet, wants to know if I’m hanging out in the ‘hood. [My hometown is] not a very racially diverse community, so that’s a shock for them, when I’m one of the only white people at my sites.”

“Yeah, I live in an unsafe neighborhood,” says Antoine Mayes, a second-term AmeriCorps member in his first term of service at the YMCA. “It’s a big deal, but at the same time, we’re part of the solution. We’re not part of the problem. I’d rather say that, even if I live in the most horrible part of town.”

Lead by example

“I come from a lousy family, a lousy support system – you kind of think that you can’t come up out of that, but being able to show young people that they can build a support system themselves, outside of their families, outside of what they come up in – showing them they can build a future – is always something that I’ve wanted to do.”

Working within the AmeriCorps framework has its challenges. The YMCA AmeriCorps program is funded at the state level on a year-to-year basis; each year the YMCA has to reapply for its grant.

“We find out in June if we’re funded, and then we start the program on September 1 – that’s a pretty short time to start talking to branches, find out how many members they want, get descriptions out on college campuses, in the newspaper, on the website, on the radio,” Renn says.

One key indicator of funding is a program’s retention rate, and while the YMCA’s rate is improving – in 2006-2007, they reported a healthy 84% retention, up from 69% the previous year – a crucial component of the program is bringing in members that kids and teens from rough backgrounds can relate to. Sometimes that means taking chances.

“Because we work with such diverse groups and in high-risk areas, we sometimes take on members who have risk factors associated with them,” says Renn. “We need to put someone in there that can relate to the teens and know what they’re going through. We can’t put someone in there who just graduated from college and grew up in Mequon.

“Sometimes it’s either the best fit ever – [or] those issues affect their service. We appeal to a board at the state level, and [we have to] help our funders understand that. It’s critical. They just see numbers, and we have to get them to understand everything going on behind those numbers.”

A cycle of service

A 2004 study of the effect of AmeriCorps service by the Corporation for National and Community Service (AmeriCorps’ parent agency) repor ted “significant positive impacts on members’ connection to community, knowledge about problems facing their community, participation in community- based activities and personal growth through service.” This was especially relevant in situations where youth considered disadvantaged by poverty, race, social circumstances or family relations were engaged in public service and volunteer opportunities;CNCS found that such volunteers were far more likely to go to college, discuss politics with their friends and family and feel empowered to make changes in their communities.

AmeriCorps alumni were more likely to continue to volunteer, and they were more likely to vote; in the 2000 elections, former AmeriCorps members reported that they voted at a rate of 72%, compared with the national average of 55%. And AmeriCorps programs are often considered a “pipeline” to careers in service; according to the same study, 66% of AmeriCorps alumni chose careers in the public sector (as teachers, social workers, public safety officers) or in the non-profit sector (in philanthropy, the arts, advocacy).

But perhaps the most promising aspect of service programs like AmeriCorps is the chance they offer to set a cycle in motion, a wheel of sowing and harvesting, giving and growing, teaching and learning and teaching again.

The day I spoke with Pat Marcus, she was working on a way for kids in the SPARK program to prepare books to send to kids in New Orleans. “I don’t think there’s anything wrong with even kindergartners giving back,” she says. “It might be something I’m not asking our kids to donate, because they don’t have the resources, but maybe they can sticker them, put in bookplates, and know that they’re sending books to someone less fortunate. Everybody likes to help. They really do. And part of what AmeriCorps likes to perpetuate is service learning … so that kids become more aware of their communities.”

Across the country and here in Milwaukee, AmeriCorps members are preparing for Martin Luther King Day on January 21 by coordinating a massive volunteer recruitment effort. 2008 marks 40 years since King’s assassination, so the CNCS is launching 40 days of service, nonviolence and social justice. It’s a perfect example of the organization’s cohesive vision for national service, connecting Americans with the emotional weight of being united in an effort on a day Coretta Scott King famously promoted as “a day on, not a day off.”

In the auditorium of the John C. Cudahy YMCA, Kendall and I are sitting on a folding cafeteria table and finishing our interview – the kids upstairs are getting squirrelly. When I ask him if there’s anything he wants to add before I pack up and turn him over to the photographer, he hesitates, then says yes.

“When I graduated from my high school, a lot of my peers said that they were preparing to leave, that they wanted to leave Milwaukee – there was a lot of violence, and there still is,” he says. “When I graduated, I used to say, ‘I can’t just leave, I can’t just forget about the people here.’ This is where I was born and raised. I choose to stay here. The AmeriCorps program may not help solve everything, but it solves something. A part of the problem is solved by being in AmeriCorps.” He believes that more people would participate in AmeriCorps if they knew about the programming it funds and the incentives it involves.

“Once you start – at first it feels like any other regular job,” Kendall says. “But over time, as you develop relationships, it doesn’t feel like it at all. I don’t think there’s any other way I can put it – it’s not really volunteering to me. I don’t feel like I’m giving up my time – I feel like I’m earning something, too.” VS