State’s Political Map At Issue

Does geography or gerrymandering give a GOP edge? U.S. Supreme Court could decide.

The object of a partisan gerrymander is to create a durable advantage for one party over another. The party designing the gerrymander will find it much easier to win more of the seats than the other party. As the next two charts show, the 2010 Wisconsin redistricting plan was wildly successful in creating asymmetry that favors Republicans.

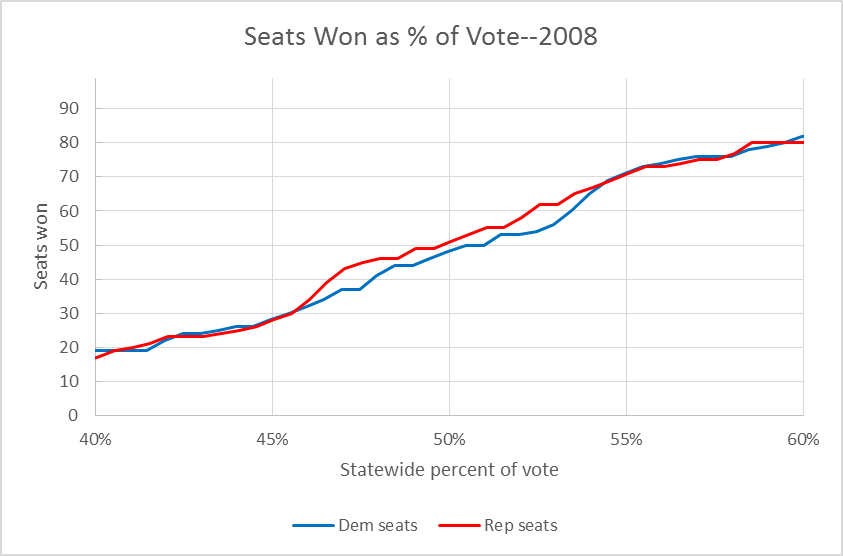

The chart below shows the estimated number of Assembly districts each party would have won in 2008 based on what percent of the statewide vote each party might have won The districts used in 2008 were drawn by a panel of federal judges following the 2000 census. It is widely agreed these judges had no desire to favor one party over the other.

As can be seen, the 2000 redistricting had a slight Republican tilt. If each candidate won half the vote, the Democrat would win 48 districts, the Republican 51.

Despite the slight Republican advantage, majority control was within Democratic reach. Merely by winning an extra half per cent the Democrat would have won a majority of districts. In the 2008 election, there was a significant number of highly competitive seats. For both candidates, going from 45 percent to 55 percent of the vote would result in a gain of about 40 more seats.

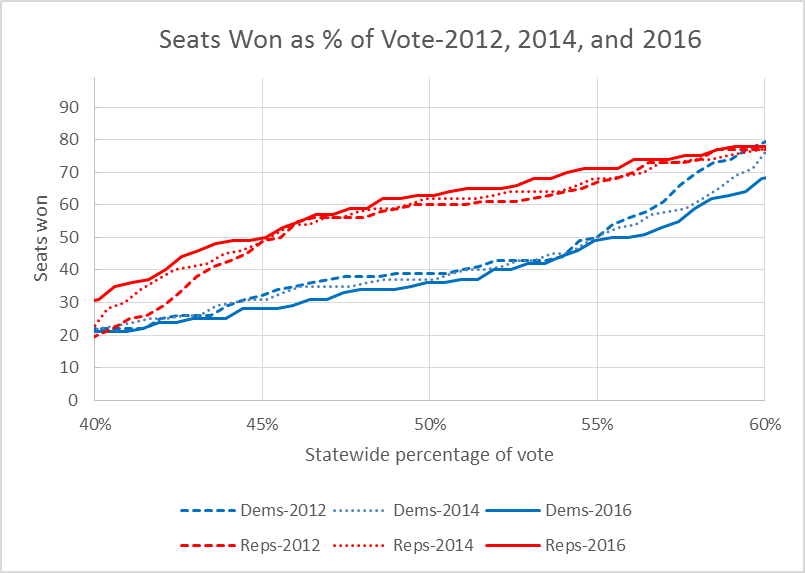

The next graph shows the partisan effectiveness of the strategy underlying the 2010 Wisconsin gerrymander, called Act 43. A huge asymmetry has opened between the abilities of the Republicans and Democrats to translate votes into legislative seats. With a tied vote, Democrats win about 20 fewer seats than Republicans.

This Republican advantage is durable. Republicans gain the majority of seats so long as they have at least 45 percent to 46 percent of the vote, while Democrats need more than 54 percent of the vote to gain a majority of seats. The flatness of the curves around the 50 percent mark reflects how few competitive districts are left.

The asymmetry in the 2010 gerrymander was achieved using what political scientists call “packing and cracking.” Although usually presented as two different strategies, packing and cracking work together. The boundaries of a district that starts competitive or slightly Democratic are altered to move Democratic neighborhoods into an adjacent district that is already heavily Democratic (“packing”). This makes room for a second boundary change to add Republican voters (“cracking”). The development of mapping software makes packing and cracking much easier than in the past.

Last fall a special federal district court agreed that the Wisconsin legislative redistricting plan is an unconstitutional gerrymander. The District Court adopted a three step test for partisan gerrymandering:

- Is the plan intended to place a severe impediment on the effectiveness of the votes of individual citizens on the basis of their political affiliation?

- Does it have that effect and is the effect likely to persist for the life of the plan?

- Can it be justified on other, legitimate legislative grounds?

The Wisconsin plan failed all three parts of the test. On the first and second steps, it was very clear from the record that it was designed with the aim of creating as many Republican seats as possible and that it achieved that aim. As to the third, the defendants offered no evidence that its design resulted from legitimate state goals.

The state appealed this decision to the US Supreme Court. The briefs can be found on ScotusBlog, including the appeal itself and the response from the plaintiffs. There are also amici briefs defending the Wisconsin gerrymander from Republican-oriented groups: the Wisconsin Institute for Law and Liberty, a group of Republican states (Texas, Arizona, Arkansas, Indiana, Kansas, Louisiana, Michigan, Missouri, Nevada, Oklahoma, South Carolina, and Utah), the Wisconsin State Senate and Assembly, Judicial Watch and Allied Educational Foundation, and the Republican National Committee.

Two of the challenges to the federal court decision are funded by Wisconsin taxpayers. One is the appeal itself from Wisconsin Attorney General Brad Schimel, representing the Wisconsin Election Commission. The other is one of the amici briefs, from the Wisconsin legislature which hired the well-known right-wing lawyer Paul Clement. Both seize on Wisconsin’s geographical distribution of Democrats and Republicans to justify the Republican bias to the 2010 redistricting.

Here is what Schimel had to say about this:

So far, electoral results for the Assembly under Act 43 have proven remarkably similar to the most recent results that obtained under the court-drawn plans. This is a reflection of Wisconsin’s political geography, where Democrats concentrate in urban areas like Madison and Milwaukee, as well as incumbency advantage. Indeed, the only way the Legislature could have attained Plaintiffs’ desired election results would have been to engage in heroic levels of nonpartisan statesmanship …”

In his amici, Clement also blames “political geography:

Even if statewide gerrymandering claims were viable, the district court’s methodology failed to adequately account for the impact of Wisconsin’s political geography. Democratic voters in Wisconsin are concentrated in urban areas like Madison and Milwaukee, while Republican voters are dispersed more widely throughout the State. As a result, any districting map based on traditional principles like compactness and contiguity (which this map concededly was) will appear to have a pro-Republican bias under the plaintiffs’ “efficiency gap” theory.

Clement goes on to assert that avoiding gerrymandering would make it harder to draw districts:

It is already hard enough to draw districts that simultaneously satisfy the competing demands of the myriad state and federal constraints on the districting process. If allowed to stand, the decision below will make it all but impossible for legislatures to perform that task without running afoul of one prohibition or another—or at least without being forced to defend against costly and time-consuming litigation …

The quotes from Schimel and Clement contain several factual assertions: (1) that Wisconsin’s geography explains most or all of the pro-Republican bias of the state’s districts, (2) that correcting for this bias would make it more difficult to meet the “traditional principles,” such as compactness, and (3) that the results were similar to those under the previous court-drawn plans. Are these assertions correct?

As already mentioned, the court-drawn plan from 2000 has a built-in Republicans bias of 3 seats when the vote is evenly split. This compares to about 40 seats under Act 43.

This is consistent with my experience when using Kevin Baas’ Auto-Redistrict model. Runs using traditional criteria for redistricting generated districts with a Republican advantage of 1 to 3 seats with a tied vote.

The political scientist Jowei Chen used software to generate 200 redistricting plans. Every one of them scored substantially better on compactness and split fewer counties and municipalities than does Act 43. Using the efficiency gap measure of a symmetry, they average -1 compared to -15 under Act 43. In the 2012 election, Republicans won 56 of the 99 districts under the map created by Act 43; none of Chen’s randomly generated maps gave Republicans a majority of districts, in line with Democrat Barack Obama’s statewide victory in that election.

Contrary to the claims of Schimel and Clement, I estimate based on the data by me, Baas and Chen that perhaps 10 percent of the Republican tilt in Act 43 results from Wisconsin’s political geography; the other 90 percent is the result of an intention to skew the results.

Both Schimel and Clement argue that partisan gerrymandering should be judged by how well a plan adheres to the traditional criteria. In his brief, Clement worries that:

After drawing districts to comply with traditional principles, legislators would have to check their work to see whether the resulting map “favored” one party.

In fact, in their zeal to gain competitive advantage, the authors of Act 43 did a poor job of satisfying the traditional criteria for redistricting, unlike, say, the 200 maps drawn by Chen. Actually designing a politically non-biased map is very compatible with complying with traditional principles.

More about the Gerrymandering of Legislative Districts

- Without Gerrymander, Democrats Flip 14 Legislative Seats - Jack Kelly, Hallie Claflin and Matthew DeFour - Nov 8th, 2024

- Op Ed: Democrats Optimistic About New Voting Maps - Ruth Conniff - Feb 27th, 2024

- The State of Politics: Parties Seek New Candidates in New Districts - Steven Walters - Feb 26th, 2024

- Rep. Myers Issues Statement Regarding Fair Legislative Maps - State Rep. LaKeshia Myers - Feb 19th, 2024

- Statement on Legislative Maps Being Signed into Law - Wisconsin Assembly Speaker Robin Vos - Feb 19th, 2024

- Pocan Reacts to Newly Signed Wisconsin Legislative Maps - U.S. Rep. Mark Pocan - Feb 19th, 2024

- Evers Signs Legislative Maps Into Law, Ending Court Fight - Rich Kremer - Feb 19th, 2024

- Senator Hesselbein Statement: After More than a Decade of Political Gerrymanders, Fair Maps are Signed into Law in Wisconsin - State Senate Democratic Leader Dianne Hesselbein - Feb 19th, 2024

- Wisconsin Democrats on Enactment of New Legislative Maps - Democratic Party of Wisconsin - Feb 19th, 2024

- Governor Evers Signs New Legislative Maps to Replace Unconstitutional GOP Maps - A Better Wisconsin Together - Feb 19th, 2024

Read more about Gerrymandering of Legislative Districts here

Data Wonk

-

Life Expectancy in Wisconsin vs. Other States

Dec 10th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Dec 10th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

-

How Republicans Opened the Door To Redistricting

Nov 26th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Nov 26th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

-

The Connection Between Life Expectancy, Poverty and Partisanship

Nov 21st, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Nov 21st, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

10%-90% sounds about right from what I’ve seen. I’d like to add that the “political geography” argument is moot to begin with, since a heuristic optimization algorithm can easily eliminate 99% of partisan asymmetry while meeting all traditional redistricting criteria. (And for millions of dollars LESS!)

To get a sense, I did a pareto front ( https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pareto_efficiency ) analysis on Wisconsin federal congressional districts (as opposed to assembly – since assembly is tougher to optimize due to more districts and fewer precincts per district):

https://docs.google.com/document/d/17dpF9xejx0T8M2VObmeWaMrP22-GdO0vC5IhKx4ICwg/edit?usp=sharing

As you can see from it ,the Wisconsin Federal Congressional are nearly as gerrymandered as you can possible get. Note that the analysis used data from 2012, 2014, and 2016, which was data not available to the map drawers. It may very well be that with the data available then, it really was the most extreme gerrymander possible.

Data Wonk articles really help me understand the issues and arguments on public policy issues. This article is a case in point.

Another well-reasoned article from Bruce. The. legal analysis is spot-on, and the fairly complex data is clearlying and persuasively explained .