1.3 Million People in State Threatened By Possible Medicaid Cuts

Federally funded care for poor, elderly and disabled helps 1 in 5 Wisconsin residents.

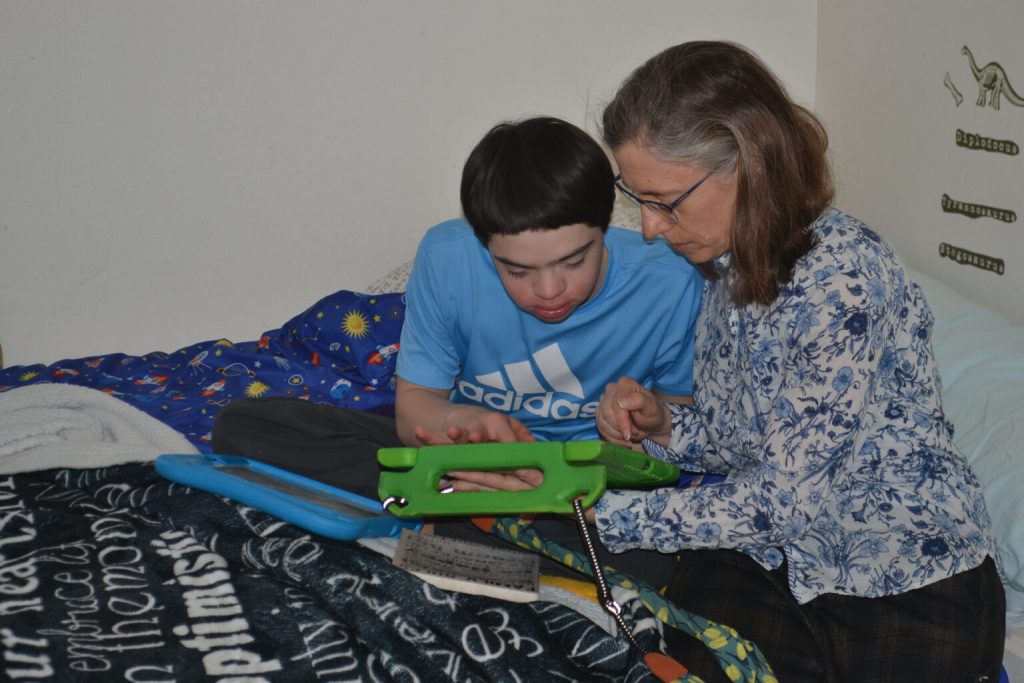

Max Glass-Lee uses an electronic communication device, picking words that the device then speaks to his mother, Tiffany Glass. (Photo by Erik Gunn/Wisconsin Examiner)

Max Glass-Lee is an energetic 14-year-old who romps through the modest home on Madison’s West Side where he lives with his mother.

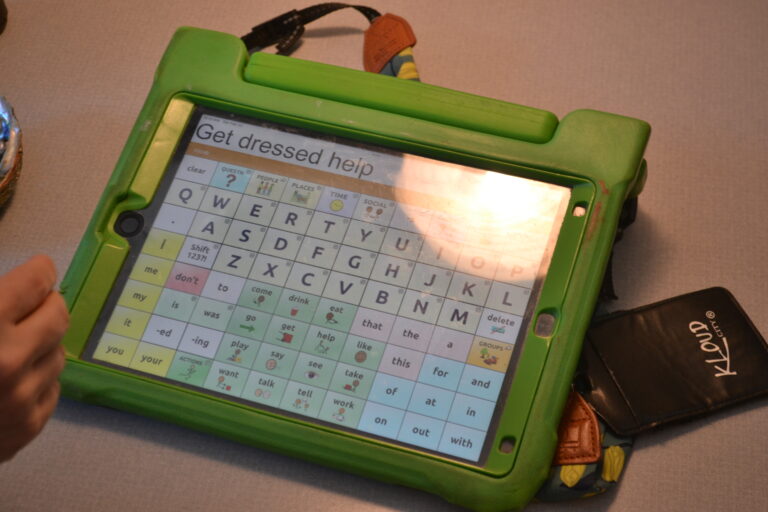

Born with Down syndrome and diagnosed as autistic, Max can read words and understand what’s spoken to him, but he doesn’t talk. Instead, he communicates with an electronic device about the size of an iPad, pressing words that the machine then speaks on his behalf. “Good-bye,” he tells his mother through the machine one recent morning, as she sits with him in his bedroom.

Tiffany Glass smiles affably, acknowledges her son’s assertion of independence, and steps out of the room.

Not so long ago, a child like Max was likely to spend his life inside the walls of an institution. Changes in social attitudes, medical ethics, and state and federal policy have made it possible for him to grow up and thrive at home.

One of those policies, says Tiffany Glass, is Medicaid — and without it, she believes Max’s life would have been much worse.

“His medical problems would not have been treated as effectively,” she says. “His quality of life would have been absolutely terrible. He would have been much more excluded from our community than he is now.”

Medicaid is the state-federal health insurance plan launched in the 1960s to provide health care for people living in poverty. In Wisconsin, it’s best known as BadgerCare Plus, which covers primary health care and hospital care for people living below the federal poverty guideline. But Medicaid touches hundreds of thousands of other Wisconsin residents as well.

More than half of Wisconsin’s nursing home residents are covered by Medicaid after spending down most of their other personal savings and assets. Other Medicaid programs provide long-term skilled care to people living in their own homes or in the community — people who are frail and elderly, but also people living with disabilities.

“I’m not sure people are aware of the lifeline Medicaid is to so many people,” says Kim Marheine, state ombudsman for the Wisconsin Board on Aging and Long Term Care. “Without Medicaid some of these people have no place to go for services.”

Congress is currently rewriting the federal budget in ways that patients, families, health care providers and advocates fear will upend the program dramatically, ending coverage for millions who have few or no alternatives.

Washington budget battle

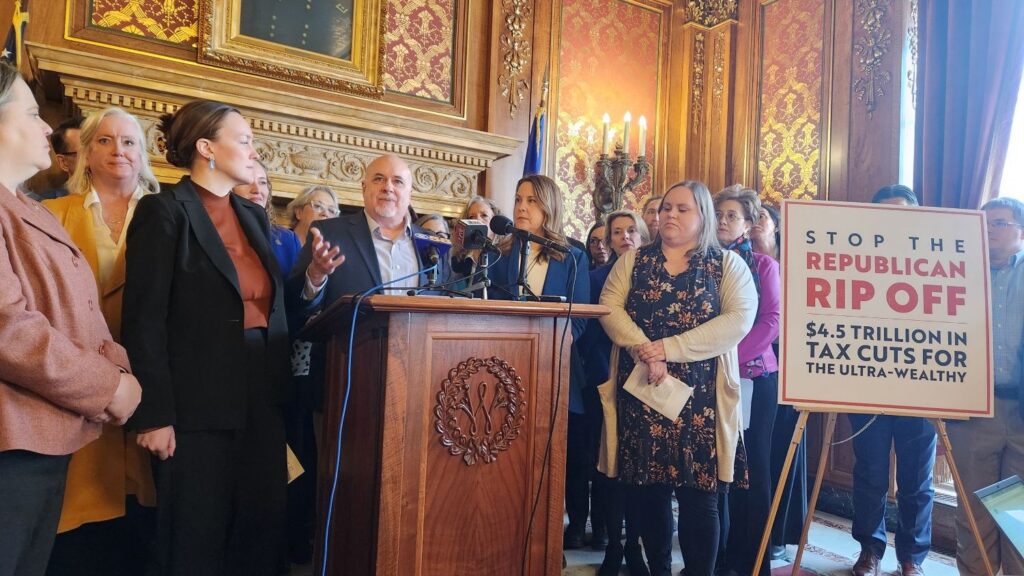

The Republican majority in the U.S. House wants to find $4.5 trillion in federal funds to pay for renewing tax cuts enacted in 2017 during President Donald Trump’s first term. On Feb. 25, the House, voting along party lines, cleared the way for a budget resolution that carves $880 billion over 10 years from programs under the purview of the House Energy and Commerce Committee.

The text of the bill doesn’t doesn’t specify where those cuts come from — a point Republicans have emphasized to rebut claims that the vote was an attack on people’s health care. Nevertheless, Medicaid “is expected to bear much of the cuts,” according to KFF, a nonpartisan, nonprofit health news and research organization.

Democratic U.S. Rep. Mark Pocan talks Wednesday, Feb. 19, about programs in Wisconsin that could be affected by Republican proposals to cut the federal budget. (Photo by Erik Gunn/Wisconsin Examiner)

“What is in the jurisdiction of that committee? Well, the largest dollar amount is Medicaid,” said U.S. Rep. Mark Pocan (D-Black Earth) at a press conference in Madison Feb. 19. Advocates dismiss Republican denials, treating Medicaid cuts as a foregone conclusion and holding GOP lawmakers responsible.

Medicaid is funded jointly by federal and state governments. Federal law guarantees that the U.S. will pay at least half of the program’s cost, with the state paying for the rest. Wisconsin has a 60% federal contribution; the remaining 40% comes out of the state budget.

For fiscal year 2023, Wisconsin’s Medicaid expenditures totaled $12.5 billion, according to the Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission, a Congressional agency. The federal government paid just under $8.2 billion of that; Wisconsin paid the remainder, about $4.4 billion.

A Medicaid reduction on the scale that the budget resolution requires “will leave enormous shortfalls for the state heading into the next two years, all so Trump and his MAGA majorities can deliver another tax cut to huge corporations and CEOs like Elon Musk,” Zepecki says. “The federal money disappearing doesn’t mean the needs disappear, which is likely to force everyone else to pay even higher costs for their own health care.”

1 in 5 Wisconsin residents

According to the January 2025 enrollment numbers from the Wisconsin Department of Health Services (DHS), about 1.3 million Wisconsin residents rely on Medicaid for day-to-day health care, long-term care or both — more than 1 out of 5 state residents.

They include more than 900,000 Wisconsinites who are enrolled in BadgerCare Plus. The health insurance plan for people up to age 65 covers doctor’s office visits, preventive care, surgery, hospital stays including childbirth, and other day-to-day health care needs for families living below the federal poverty guidelines. Children are covered in families with incomes up to 300% of the federal guideline; BadgerCare covers one-third of Wisconsin’s children.

Medicaid also covers alcoholism treatment, substance abuse treatment and other forms of care for mental health. “Medicaid is one of the largest payers of mental health care in the state,” says Tamara Jackson, policy analyst for the Wisconsin Board for People with Developmental Disabilities. It is the major funder of county mental health services, whether provided directly by a county agency or in partnership with a community agency, according to the Wisconsin Counties Association.

Covering mental health is more than simply covering the cost of medications that may be prescribed. “Depression and anxiety medications are most effective in combination with the use of counseling services,” says Sheng Lee Yang, an Appleton clinical social worker. But if patients prescribed a medication aren’t able to get counseling as well, “their symptoms are only being treated at a 50% rate. That’s not real effective.”

Medicaid is part of health care all across Wisconsin. A study from Georgetown University’s Center for Children and Families released in January found that residents of rural counties in the U.S. are more likely to rely on Medicaid for their health coverage than urban residents. In 27 northern and central Wisconsin rural counties, the share of children on Medicaid is higher than the state average, the study found.

Medicaid’s reach doesn’t stop there, however. Through nearly 20 different programs, Medicaid covers the health care of more than 260,000 additional Wisconsin residents.

For about 10,800 frail, elderly people who could not otherwise afford nursing home care, Medicaid pays the cost — about 60% of the state’s nursing home population.

To join those programs states apply to the federal government with proposals that would waive standard Medicaid rules. The idea is that if someone who needs long-term care can remain at home or in another homelike setting, the overall cost of care will be far lower than in a nursing home, stretching the Medicaid dollar farther.

More than 43,000 frail elderly or disabled adults in Wisconsin receive long-term care at home or in the community — in assisted living, for instance — under Medicaid waivers. Family Care began piloting in individual Wisconsin counties about 25 years ago as a nursing home alternative. It has since gone statewide, joined by allied programs that allow people to customize their care plans.

For elderly relatives who needed the intensive level of care offered by a nursing home, Family Care “gave them a tremendous alternative to skilled nursing care,” says Janet Zander, the advocacy and public policy coordinator for the Greater Wisconsin Agency on Aging Resources.

“A lot of work Wisconsin has been doing, and other states as well, has been shifting how we provide care to people’s homes,” says Jackson.

Care at home instead of an institution

Beth Barton’s daughter, Maggie, was born 25 years ago with cerebral palsy. She doesn’t talk and is not able to move about on her own, and for her whole life she’s needed complex medical care, Barton says.

One of Medicaid’s earliest waiver programs is named for Katie Beckett, a child from Iowa whose story led the Reagan administration in the 1980s to authorize long-term health care at home for children with disabilities instead of only in a hospital or nursing home. In Wisconsin, there are about 13,500 children enrolled in the state’s Katie Beckett waiver program.

When Maggie was a child, the Katie Beckett waiver enabled the Barton family to care for her at home. The family’s health care comes through the company plan where Beth Barton’s husband works. Medicaid served as a secondary insurer for Maggie, covering insurance copayments and for her care that the family insurance didn’t pay for.

Growing up, Maggie was able to attend Lakeland School, a public Walworth County school for children with disabilities. School “was difficult” her mother says, but it also provided rewarding interaction for her daughter. The school’s therapeutic pool became part of Maggie’s daily routine, where “she could be free,” Barton says, able to enjoy sensory experiences outside her wheelchair.

After Maggie turned 18, she was enrolled in IRIS — a Medicaid-funded long-term care program. While Family Care works though contracts with managed care providers, IRIS, a more recent variation, allows people to make their own arrangements for services, including home health care and personal care.

IRIS Medicaid funding helps pay for a social worker who visits four times a year and respite care when Barton can’t be at home. It also covers home modifications, such as an accessibility ramp.

Without the support Medicaid has provided throughout Maggie’s life, Barton believes her daughter might well have ended up in an institution. She’s not optimistic about that option.

“Her unique needs are best met one-one,” Barton says. “If we didn’t have private duty nursing, if we didn’t have Medicaid to meet those needs, I honestly don’t think she’d be with us.”

Children’s long-term support

Another Medicaid waiver covers certain purchases children with disabilities need as they grow up.

Danielle Bauer’s 3-year-old son, Henry, was born with Down syndrome and has also been diagnosed with autism. The family lives in Wausau, and Wisconsin’s Children’s Long-term Support waiver helped cover the cost of a sensory chair that offers Henry “a quiet retreat to prevent meltdowns,” Bauer says. The family also got coverage for a specialized high chair that will grow with him as he gets older.

“It has made a huge difference in his quality of life,” Bauer says of her son. “He is capable of so much more, but without these supports, families don’t have resources to help kids like him.”

Until Jessica Seawright’s son was born nine years ago, she and her husband had no inkling their child would have a disability, let alone a serious one. Because of a chromosome abnormality, he has cerebral palsy and uses a wheelchair.

The Children’s Long-term Support waiver helped the family purchase a wheel-chair van to transport their son. It also helped cover the cost of widening a doorway in their home on the South Side of Milwaukee so he can get into the bathroom using his chair.

Seawright is a social worker and therapist. Her employer provides the family’s primary insurance, with the couple paying about $300 a month toward the premium as well as covering their own medical and dental copayments.

The Katie Beckett waiver has made it possible for Medicaid, through BadgerCare, to pick up her son’s medical costs, Seawright says. He often has to go to the emergency room and has other complex medical needs. He has recurring seizures, and he has trouble swallowing and needs a gastric tube. He’s been prescribed various medications and formula supplements as well.

Without that support, she says it’s likely that the family would burn through the $5,000 annual cap on their out-of-pocket health care costs.

“We would be making really tough choices — what can we afford out of pocket each year? It would be a question of how often we pay for foot braces when he outgrows them,” Seaward says — along with the medications, supplements and formula he needs.

“It’s not that we don’t want to pay for our fair share, but with the cost of his care it’s not possible to keep up with,” she says.

Moving past ‘a dark part of our history’

Tiffany Glass is a University of Wisconsin research scientist, studying why children with Down syndrome often have trouble eating, drinking and swallowing. She was in the process of deciding what direction she wanted her research career to take when her son Max was born; his diagnosis pointed the way.

“Up until the mid-1980s in the United states, a lot of children with Down syndrome and other disabilities were institutionalized, because their communities didn’t have the resources to accommodate them,” Glass says.

UW medical ethicist Dr. Norman Fost wrote in a 2020 journal article that as recently as the late 1970s it wasn’t unheard of for parents to allow newborns with Down syndrome to die without medical intervention.

“It’s a really dark part of our history,” Glass says.

Medicaid changed that for Max — supporting him for his medical care, communication (it paid for the electronic tablet that speaks for him), and activities of daily living.

Although Max Glass-Lee doesn’t speak, he can use this electronic device to communicate by pointing to words or spelling them out. The device then speaks for him with a computer-generated voice. (Photo by Erik Gunn/Wisconsin Examiner)

“He needs help with all of those things,” Glass says. “It adds up to needing skilled care 24 hours a day, seven days a week. For his whole life he’s required that type of care, and he probably always will.”

In addition to providing resources for Max’s care at home, Medicaid has also enabled Glass to pursue her scientific calling. Without it, her research career might have stopped before it started, she says.

Regular child care centers are unlikely to take someone whose disabilities are as severe as his, she has found, but the children’s long-term support waiver has covered the cost of respite care.

“That has allowed me to work outside the home for a decade as a research scientist,” says Glass. “If Medicaid hadn’t been there, I probably would not have been able to develop my research career. I would have had to stay home — to the detriment of scientific research.”

Now, however, she and countless others who have come to rely on the program — adults and children, people with disabilities and caregivers for elderly relatives — have grown anxious about whether they will still be able to count on the care that Medicaid has made possible.

“Those arrangements are still very fragile,” Glass says. “We’re all very worried that if funding for Medicaid is reduced or eliminated, that could have really terrible implications for our families.”

This story is Part One in a series.

Wisconsin patients, families are wary as Congress prepares for Medicaid surgery was originally published by the Wisconsin Examiner.

If you think stories like this are important, become a member of Urban Milwaukee and help support real, independent journalism. Plus you get some cool added benefits.