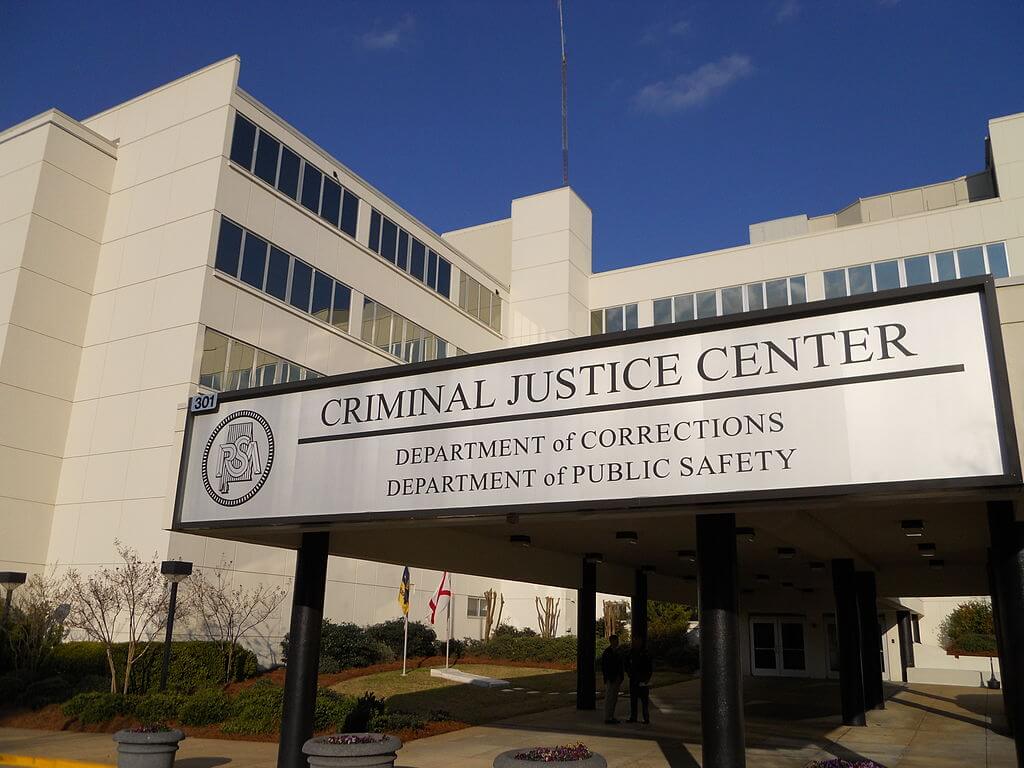

State Bonding to Help Finance Alabama Prisons

Questions about Wisconsin’s Public Finance Authority and proposed private prisons blasted as a 'golden gulag.’

The Alabama Criminal Justice Center houses the headquarters of the Alabama Department of Corrections and the Alabama Department of Public Safety. Photo by Rivers A. Langley; SaveRivers, (CC BY-SA 3.0), via Wikimedia Commons

A group of proposed privately owned prisons in Alabama has drawn scrutiny and criticism of the little known Wisconsin financing authority that is raising money for the project.

Nearly three dozen activists and investors have signed an open letter urging banks and investors not to take part in the project’s bond offering, originally for more than $600 million, to help finance the building of two new privately owned prisons that would be leased back to the state of Alabama.

“The PFA and the state of Wisconsin should have no part of this new golden gulag for the private prison industry,” says Matt Nelson, the Milwaukee-based national executive director of Presente.org, an organization of Latinx activists.

On Thursday, as bonds were to go on the market, the lead underwriter postponed the offering and reduced it by nearly one-third its value. Bloomberg News reported that Barclays, the United Kingdom bank underwriting the offering, put off the sale until Monday, April 19, and lowered the dollar amount of bonds offered to $436.2 million from the original $633.5 million figure in the offering’s March 31 preliminary statement.

Nelson welcomed the announcement. “Barclays’ decision to delay their municipal bond sale to finance private prisons in Alabama is a step in the right direction,” he says. “However, we need them to live up to their commitment to stop financing private prisons, and along with the PFA, they need to cancel the deal altogether.”

‘Refuse to purchase…’

The delay and downsizing came a day after a network of investors and activists announced their campaign to dissuade potential purchasers of the bonds. Christina Hollenback, an investment firm partner, organized the campaign, which launched with an April 12 letter.

“We strongly urge banks and investors to refuse to purchase securities that will be offered on April 15 whose purpose is to perpetuate mass incarceration,” the letter states. The campaign followed up with a press announcement Wednesday, April 14.

“As young people, we absolutely are interested in making sure that our investments are aligned with our values,” she says. “We do not believe that we should be expanding mass incarceration: It has been a huge drag on our economy, it’s done enormous — it almost feels like irreparable, to be honest — harm to Black, brown and indigenous communities. And our generation is not going to stand for that.”

Alabama’s prison system has been the target of criticism for decades. The U.S. Department of Justice sued the state in December 2020, accusing the state of violating the 8th Amendment with unsafe prison conditions, including extensive violence and the excessive use of force. The lawsuit followed a scathing report on the system in April 2019.

In response to the DOJ report and subsequent lawsuit, the Alabama Department of Corrections and Gov. Kay Ivey have embraced a plan to build three new prisons to replace a half-dozen or more old ones that house about half of the state’s 20,000 prisoners.

Two of the facilities would be built by CoreCivic — a private prison operator formerly called Corrections Corp. of America — which would own the prisons and lease them back to the state.

Record incarceration rate

The project has been billed as replacing dilapidated and overcrowded prisons with new, modern facilities. Critics argue that ignores the larger problem that too many people are in prison as well as CoreCivic’s track record.

“Right now Alabama incarcerates people at a 50% higher rate than the rest of the country,” says Morgan Duckett, a senior at Auburn University and a leader of Alabama Students Against Prisons, part of a coalition against the project that includes the American Civil Liberties Union and the Southern Poverty Law Center. Black people account for about one-fourth of the state’s population but more than half of its prisoners, according to the Prison Policy Initiative, a national research and advocacy organization.

“There are no good reasons why we’re jumping into bed with for-profit corporation CoreCivic—a company with a record of abuse and mismanagement,” Zeigler wrote in an op-ed article criticizing the governor’s plan.

Over the objections, Alabama has gone ahead with the project.

The bonds authorized by Wisconsin-based PFA are for the two CoreCivic facilities. As originally structured, about $215 million of the financing was to be through a private placement, with the remaining $633 million through taxable bonds authorized by the Wisconsin-based PFA.

With reduction in the bond amount disclosed on Thursday, Bloomberg News reported, it wasn’t clear whether the private placement portion of the deal would get a corresponding increase. With Barclays as the lead underwriter, additional financing support is being provided by KeyBanc Capital Markets and Stifel, Nicolaus & Co. Proceeds from the sale will go to CoreCivic as the borrower.

Wisconsin’s role in the deal

PFA entered the project after it was approached by the underwriters, according to Andy Phillips, a lawyer with the Milwaukee firm von Briesen & Roper who is general counsel to the PFA, in a written statement to the Wisconsin Examiner.

Barclays’ involvement has compounded criticism of the project. Two years ago, the UK bank said it would stop financing private prisons. According to the Financial Times, Barclays has responded that its earlier commitment “remains in place,” and that the company is financing the prisons on behalf of the state of Alabama, which will lease and operate them.

Hollenback dismisses that distinction. “Barclays is saying, ‘We’re just working with the state of Alabama, and the fact that the state of Alabama is working with CoreCivic doesn’t have anything to do with us,’” she says, paraphrasing the bank’s stance. “Well, no. It absolutely has to do with Barclays’ investments.”

The letter also warns that investors face “reputational risk”: “By participating in this deal, investors will be giving their imprimatur to harsh, life-threatening incarceration and historically incompetent day-to-day management of prisoners, as well as uplift of a historically horrific actor in CoreCivic and the private prison industry, in general,” the letter states.

Along with groups in Alabama that have organized to try to stop the project and the investors group seeking to discourage the bond sale, activists in Wisconsin have begun to challenge the transaction, focusing on the role of the PFA.

The PFA was created in 2010 when lobbyists for national cities and counties organizations sought “to improve access to funding and accelerate economic growth,” the Wall Street Journal reported in 2019, adding: “They chose Wisconsin as the PFA’s headquarters because of the state’s accommodating laws.”

Four counties — Adams, Bayfield, Marathon and Waupaca — along with the city of Lancaster, created the PFA after the Legislature unanimously passed a state law that allowed for the creation of the commission. The League of Wisconsin Municipalities, the Wisconsin Counties Association, the National League of Cities and the National Association of Counties are sponsors of the authority and collect annual payments from the PFA, according to a 2019 Legislative Fiscal Bureau report.

Through 2020, the PFA has been involved with about 385 bond offerings, according to records posted by the Wisconsin Department of Revenue. Its cumulative bonding has exceeded $10 billion, most of it on out-of-state projects.

“The Public Finance Authority was created by local governments, for local governments, with the goal of providing a public-private partnership option for affordable financing of public benefit projects, at no risk to the taxpayer, across the country,” says Phillips, the PFA’s lawyer, in his written statement. Projects include tax-exempt as well as taxable bond financing.

Challenging the transaction

The PFA has also drawn criticism. The 2019 Wall Street Journal article focused on reports that the authority was associated with an unusual amount of risky debt. Republican lawmakers in Wisconsin have criticized the authority for its involvement in out-of-state projects, and federal tax authorities have charged some of those projects didn’t qualify for tax-free bonds.

With the prison project, Alabama activists have questioned whether the PFA skirted its own requirements.

The PFA website’s FAQ (frequently asked questions) page includes a statement that federal tax law as well as the authority’s founding agreement require a public hearing and approval before the PFA will issue bonds.

“That hasn’t happened,” says Duckett, the Alabama Students Against Prisons leader. Duckett says he spoke with a county official where one of the prisons is to be built. “He has had no contact at all about this prison and is staunchly against it.”

In his statement to the Examiner, Phillips says that in using taxable bonds the project was “not subject to the same public hearing requirements as a tax-exempt project.” Phillips adds that “the PFA went beyond state or federal requirements and sought specific approval from the State of Alabama for this bond deal. The Governor of Alabama provided approval on this project.”

Among the arguments that opponents have made against the project, however, is the Alabama governor’s unilateral authorization. Organizations fighting the project are preparing to sue, citing a state law that specifies the Department of Corrections “cannot go into a lease agreement with a private entity without consent of the Legislature,” Duckett says.

In Wisconsin, Matt Nelson, the Presente.org director, says he and others have begun contacting local and state lawmakers and other elected officials to raise concerns about the prison project and PFA’s involvement.

Outreach efforts could extend to Gov. Tony Evers, activists say. The governor’s 2018 financial disclosure report includes investments in the PFA; since he took office, however, Evers’ assets have been in a blind trust.

Nelson isn’t opposed to the PFA in concept “to finance projects that benefit economic stability, that benefit education and infrastructure and health care,” he says. “A private prison is not what it should be used and leveraged for.”

Reprinted with permission of Wisconsin Examiner.

One of PFA’s projects is the American Dream Meadowlands megamall in New Jersey. A knockoff of the Mall of America and West Edmonton Mall, the project was faltering until PFA and a New Jersey agency helped to sell $1.15 billion in unrated revenue bonds to ensure its financing. But then, just today, we see that the mall’s owners are defaulting on their construction loans. Ooops.

https://jerseydigs.com/american-dream-owners-default-on-1-2-billion-construction-loan/