Did State Retaliate Against Whistleblowers?

Two state employees say they were harassed after reporting suspected fraud at their agencies.

Nicole Teasley says she was ostracized after uncovering what she believed was timecard fraud by employees of the Milwaukee Enrollment Services office. Teasley left her state Department of Health Services job after filing a state whistleblower complaint and agreeing to a financial settlement with the agency. Photo by Coburn Dukehart/Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism.

Suzanne Weber and Nicole Teasley were both state employees doing what they thought was right.

Each woman tried to save taxpayer money from being wasted within their respective agencies by calling attention to poor financial practices. However, instead of being rewarded for their efforts, each woman faced a litany of actions that they say punished them for speaking out.

When Teasley first offered to perform audits of her office’s payroll system around 2010, her bosses at the state Department of Health Service’s Milwaukee Enrollment Services lauded her initiative. MilES helps to connect Milwaukee residents with local government services. However, as she began to uncover what she believed to be systemic fraud and time theft within the MilES office, the attitudes of her supervisors changed, she says.

At first, Teasley thought that this might be a simple oversight on the part of supervisors, but as she did more digging, she found that this alleged theft had been going unchecked for years. Failing to claim sick or vacation time not only pays employees for time they did not work, but allows them to stockpile days that they can use to buy health insurance in retirement.

As human resources director, performing these kinds of audits was not in Teasley’s job description, and she undertook the task in hopes of creating a more efficient office. After her first round of checks, she changed the payroll system from positive to negative, meaning employees no longer started with a full 80-hour pay period time card, deducting hours accordingly, but had to manually put in all their hours. Even with these changes, she alleges the time theft still went on.

“That’s when I began to consider this a problem,” Teasley said. “I mean, you’re physically going in and saying you’re working when you’re not working.”

Nicole Teasley says she knew there was “no going back” when she filed a complaint alleging she was retaliated against by the state Department of Health Services for blowing the whistle on alleged timecard fraud by employees at the Milwaukee Enrollment Services office. A DHS spokeswoman said the agency found “there was no wrongdoing.” Teasley left the agency after reaching a financial settlement with DHS. Photo by Coburn Dukehart / Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism.

Teasley estimates that roughly 25 percent of employees at her office were taking advantage of time theft, with one woman collecting as much as one month’s full pay while on an unpaid leave of absence.

“Supervisors, it’s ultimately their responsibility to make sure when they’re approving a timecard, they’re certifying it for payment, and by not doing it, they’re negligent in their tasks and allowing employees to get off on the system,” Teasley said.

Three years after she began raising the alarm about the timecard system, in 2013, Teasley filed a retaliation complaint, alleging that she began to have responsibilities stripped after she blew the whistle. Supervisors removed her from projects they had previously commended her for taking on, she says.

In one episode she described as humiliating, Teasley says she was kicked out of the monthly supervisor meeting in front of her peers and coworkers. She claims that began a period of her dismissal from meetings that culminated in an involuntary reassignment.

Nicole Teasley says she was retaliated against after she uncovered what she believed was systemic fraud in the reporting of vacation and sick days within the Milwaukee Enrollment Services office, seen here. The Department of Health Services denied there was any wrongdoing. Photo courtesy of CBS 58 News.

“When I decided to pursue my complaint, I knew there was no going back because of the history I saw with the department and how they treat employees who file formal complaints,” Teasley said. “I personally witnessed how they treated other employees who went down that road, so I knew going into it how I was going to be perceived moving forward. And I had to take that leap of faith knowing I was going to be okay.”

An initial investigation ruled that there was no probable cause for Teasley’s allegations of retaliation. Teasley appealed that decision before an administrative law judge. The judge overturned the investigator’s finding and decided Teasley likely had faced retaliation. Shortly after, in 2015, DHS settled for $12,500, and Teasley found work elsewhere.

In 2013, Milwaukee’s Shepherd Express found other problems in the MilES office, including alleged nepotism and favoritism. In a 2015 report, the alternative newspaper reported on alleged retaliation against other whistleblowers in the agency.

Asked if the DHS had changed its policies for preventing fraud in the wake of Teasley’s complaints, spokeswoman Julie Lund denied that there was any time theft in the first place.

“The settlement agreement clearly states there is no admission of liability, and the department maintains there was no wrongdoing,” Lund said.

Whistleblower targeted after finding fraud

Weber was a career state employee who had been at the Department of Workforce Development for three years before she was assigned to the Wisconsin Employment Transportation Assistance Program in 2003, a joint effort between the state and federal governments to help connect workers with sustainable employment that would have otherwise been inaccessible.

WETAP was run by the DWD and the state Department of Transportation. One program Weber helped institute in 2005 was the Stoughton shuttle, a collaboration between WETAP and Dane County to transport low-income Madison residents to jobs in Stoughton, with the goal that workers would eventually buy cars and establish carpools.

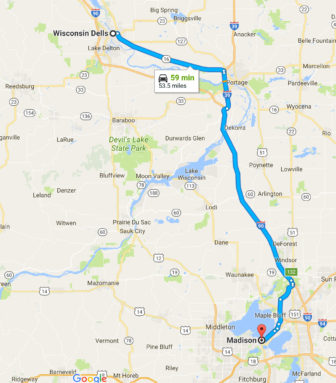

After the state paid invoices for nearly eight months, Weber got a shocking call. The Stoughton shuttle had never run. Instead, Dane County had used the funds to bring Madison-area residents to interview for jobs cleaning hotels in Wisconsin Dells. Rather than the 38-mile round-trip from Madison to Stoughton, these workers were being shuttled back and forth about 100 miles to interview for low-wage jobs.

Rather than a 38-mile round-trip from Madison, to Stoughton, Wis., state whistleblower Suzanne Weber discovered the state and federally funded Stoughton shuttle service was taking low-income workers on a more than 100-mile round-trip for job interviews in Wisconsin Dells, Wis., seen here. Weber says she was retaliated against after she blew the whistle on the alleged misspending in the transportation program. Photo by John Hart / Wisconsin State Journal.

Dane County also provided shuttles to a construction project in Beaver Dam, though these temporary jobs did not appear to meet the requirement that transportation be provided only for permanent employment, she says.

Part of WETAP’s mission is to provide access to sustainable jobs that cannot be found near the employee’s home — not minimum-wage work. In total, WETAP dedicated $90,682 to the program, according to WETAP administrative cost sheets. Weber thought the DWD had only one possible response.

“They’re not doing the project. They can’t be paid — period,” Weber said.

The drive from Madison to Wisconsin Dells is about 100 miles round trip. After the Department of Workforce Development paid invoices for almost eight months for a shuttle to drive people 38 miles round-trip from Madison to Stoughton, Suzanne Weber discovered they were being driven to Wisconsin Dells to interview for low-wage jobs instead. Map from Google Maps.

However, she says higher ups at both her agency and the state DOT received pressure from Dane County to pay for services rendered. Weber says she was replaced by another DWD employee who, in her opinion, did not properly oversee the program. She later filed a whistleblower complaint alleging she was retaliated against after reporting the misspending.

“I think they were just rubber stamping it (WETAP), I don’t think they were looking,” Weber said.

Nevertheless, she says the DWD was pushed to agree to other invoices, including a car repair program in Dane County that received $33,000 yet had not begun to operate.

DWD spokesman John Dipko said the agency continues to review expenditures in the program and, “We have not uncovered or been made aware of irregularities regarding WETAP in at least the past several years.”

He adds that Weber’s claims date back to the administration of Democratic Gov. Jim Doyle, predating the Republican administration of Gov. Scott Walker. He referred any further questions to the DOT. The DOT referred any questions back to the DWD.

A Dane County representative claims that none of its current staff was familiar with allegations raised by Weber.

Eventually, Weber was transferred from WETAP to a new program for which she alleges she was not given the proper training, prompting another whistleblower retaliation claim. After a settlement was eventually reached, she continued to work in the office for nearly a year and a half with relatively few problems. That all changed when a new supervisor came.

A federally and state-funded ride service for low-income workers was supposed to take people to Stoughton, Wis., seen here, but instead Dane County transported them to Wisconsin Dells, Wis., whistleblower Suzanne Weber says. She reached a financial settlement with the Wisconsin Department of Workforce Development in 2014 and retired in 2015 after filing multiple whistleblower complaints.

Weber alleged in another whistleblower complaint that she was given extra work without additional training and expected to complete projects that she says her bosses knew would require unpaid overtime.

“You feel rotten,” Weber said. “When they first start doing it, I was just crushed because I had never in my life had any kind of problems where I didn’t perform, I was always looked at as a very good employee.”

During her time at DWD, Weber also had been granted a flexible schedule, which allowed her to leave work to attend physical therapy sessions for a heart condition every Friday. She says she always made up for the hours by working from home or spending more time in the office. When her new supervisor told her that she would no longer receive this schedule, Weber decided she had enough.

After yet another formal complaint, Weber received a $25,000 settlement from the DWD and retired in June 2015.

“The DWD wanted to assure that others would not be tempted to report any wrongdoing at DWD because of the problems I encountered,” Weber said. “They wanted a deterrent for others.”

This story was produced as part of an investigative reporting class in the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication under the direction of Dee J. Hall, the Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism’s managing editor. The nonprofit Center (www.WisconsinWatch.org) collaborates with Wisconsin Public Radio, Wisconsin Public Television, other news media and the UW-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by the Center do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.

Broken Whistle

-

Doctors Side Against Injured Public Workers?

Jan 21st, 2018 by Alexandra Hall and Dee J. Hall

Jan 21st, 2018 by Alexandra Hall and Dee J. Hall

-

Court Ruling Weakens Whistleblower Law

Dec 4th, 2017 by Bobby Ehrlich

Dec 4th, 2017 by Bobby Ehrlich

-

Anti-Fraud Law’s Repeal Hurts Taxpayers

Nov 6th, 2017 by Julie Spitzer and Dee J. Hall

Nov 6th, 2017 by Julie Spitzer and Dee J. Hall