After Pioneering Work Release for Prisoners, Wisconsin Goes Backwards

Today, corrections officials don't even know how many prisoners have such jobs.

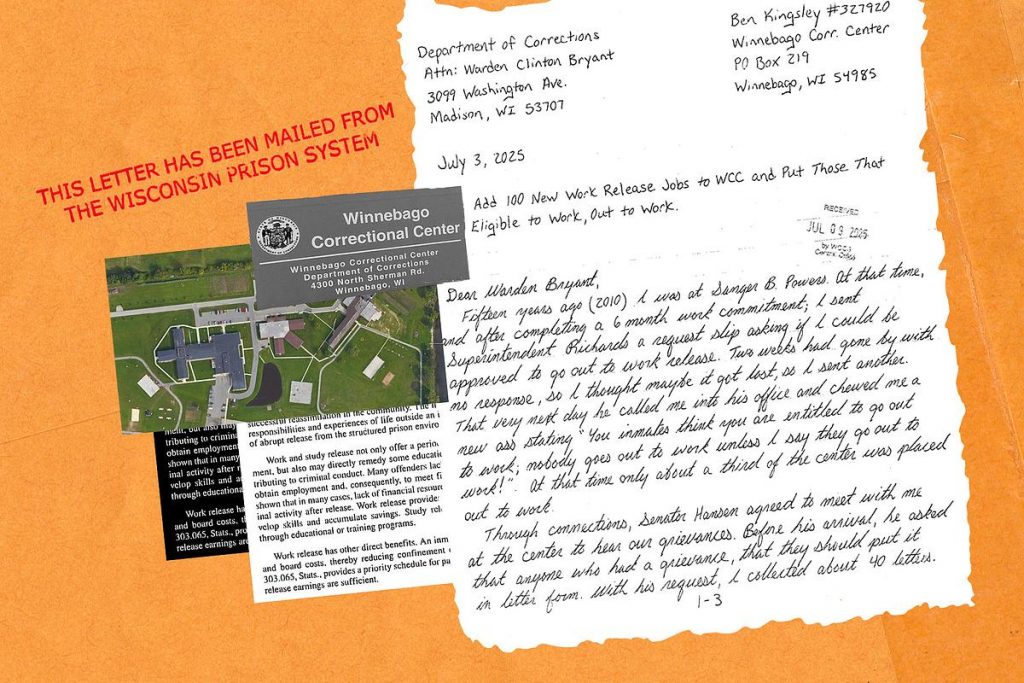

A photo illustration shows a letter Ben Kingsley wrote to Warden Clinton Bryant about the lack of jobs for people incarcerated at Winnebago Correctional Center. Kingsley contacted Wisconsin Watch with his concerns, and reporter Natalie Yahr investigated. (Photo illustration by Joe Timmerman / Wisconsin Watch)

Most of the jobs available to Wisconsin prisoners are paid not in dollars, but cents. Minimum wage laws don’t apply behind bars, so some people scrub toilets for less than a quarter an hour.

Wisconsin was the first state to offer this opportunity, known as work release. The century-old program matches the lowest-risk prisoners with approved employers, who are required by law to pay them as much as any other worker. In some cases, that’s more than $15 an hour.

Through those jobs, prisoners boost their resumes, pay court costs and save up for their release. Employers find needed workers. And taxpayers save money, since work release participants must pay room and board.

Ten of the state’s 16 minimum-security correctional centers are dedicated to work release. But prisoners at those facilities say there aren’t nearly enough of those jobs to go around, and officials at the Department of Corrections say they’re not keeping count.

Sturtevant Transitional Facility is shown Oct. 2, 2025, in Sturtevant, Wis. It includes a minimum-security unit focused on work/study release, which includes matching lowest-risk prisoners with approved employers. (Jonathan Aguilar / Milwaukee Neighborhood News Service / CatchLight Local)

One prisoner told Wisconsin Watch he believes less than a third of those eligible at his facility have such work release jobs. Prisoners routinely wait many months for the opportunity, he said, and many never get it at all.

“Having that money saved up to, say, get an apartment or get furniture, or even money for transportation?” said Ben Kingsley, 47, who wrote to Wisconsin Watch in August from Winnebago Correctional Center, a work release center in Oshkosh. “These guys know what’s at stake … They want to go out to work.”

Only prison officials can add more positions, and he questions whether they’re trying. This summer, he began lobbying prison officials and lawmakers to expand the opportunity.

“The DOC/State employees are doing the bare minimum in trying to put more people out to work,” he wrote to legislators in October.

Work release jobs are scarce, prisoners say

To qualify for work release in Wisconsin, a prisoner must be classified in the lowest custody level (“community custody”) and have permission from prison officials. In some states, eligible prisoners search for jobs on their own and can work in any role that meets Department of Corrections standards. In Iowa, for example, work release participants are barred from bartending or working in massage parlors.

“Placements cannot be guaranteed for all eligible inmates,” reads Winnebago Correctional Center’s official webpage. “Work release and offsite opportunities are a privilege, not a right, and are provided at the discretion of the center superintendent and warden.”

About 70% of eligible people incarcerated at Winnebago don’t have work release jobs, Kingsley estimates.

Kingsley, who hopes to qualify for work release after his custody status is reevaluated next year, said he began advocating for more jobs after hearing from eligible prisoners waiting to be “put out to work.”

To find out how many people were working, he asked prisoners who work as drivers, shuttling work release participants to and from their jobs.

Of the 295 people incarcerated at Winnebago at the end of October, 224 had the lowest custody status, which is required for work release, according to the Department of Corrections. By Kingsley’s calculations, just 67 have work release jobs. That’s less than one in three.

“Oh gosh, it’s a huge concern,” Kingsley said.

Officials offer explanations. Not everyone who’s eligible wants a work release job, said Department of Corrections spokesperson Beth Hardtke. Some are in education, therapy or substance use treatment programs that don’t allow them to work full time. And those who seek work release must first work at least 90 days in a prison job, followed by a stint on a “project crew” supervised by Corrections staff, before getting permission from the warden or superintendent.

“The capacity of the work release program is not just about the number of jobs available,” Hardtke said when asked whether the department is looking to add more jobs. “The program must be limited to the number of individuals that DOC staff can safely support and in settings where we can safely support them.” As Wisconsin Watch has previously reported, the Department of Corrections has been plagued by crippling staff shortages in recent years.

Additionally, Hardtke said, some can’t do manual labor. “Some individuals may not meet the employer requirements or standards, and some individuals may not have the level of training or skills necessary to complete certain tasks or jobs … As the prison population ages, some individuals may not be able to succeed in those types of work or have an interest in doing work that can have a physical toll.”

Officials and prisoners tout benefits

Work release got its start in 1913 when the Huber Law, named for Progressive Republican lawmaker Henry Allen Huber, created the opportunity at Wisconsin’s county jails. It later spread to state prisons and to nearly every state in the country.

More than a century later, Wisconsin prison leaders continue to extol the virtues of letting people leave prison and return at the end of their shifts.

Research suggests people who participate in work release programs are less likely to return to prison. A study of former prisoners in Illinois from 2016 to 2021 found those who had held work release jobs were about 15% less likely to be rearrested and 37% less likely to be reincarcerated.

“Work release really is a significant part of keeping our community safe,” Cooper said.

Work release also offsets some of the taxpayer costs of imprisonment. Each participating prisoner must pay $750 a month for room and board, about 20% of the roughly $3,650 a month the state pays to incarcerate each prisoner in the minimum-security system. They must also use their wages to make any legally mandated payments, including child support and victim restitution.

In 2010, for example, 1,726 work release prisoners collectively paid more than $2 million in room, board and travel costs; more than $320,000 in child support and more than $350,000 in court-ordered payments, according to a department report.

Work release jobs aren’t without controversy. In Alabama, a 2024 investigation by the Associated Press revealed prisoners were being pressured to work and faced retribution if they refused. Some were denied parole, despite working for years in fast-food restaurants and other jobs in the community. Critics argue the program is a modern version of the post-Civil War practice of convict leasing, in which prisons rented incarcerated people out for forced labor.

In many states, including Wisconsin, work release participants aren’t classified as employees and don’t have all the same workplace rights. But advocates for incarcerated workers told the AP that many people behind bars want to work and that eliminating the program would only hurt them.

For men in Wisconsin prisons, work release jobs are usually in manufacturing. For women, there are jobs in food service or cosmetology too. They’re “low-level, intensive labor jobs,” Kingsley said, but people are eager for the chance to start saving, especially since a criminal record and gaps in work history could make it tough to find work when they get out.

“When you get locked up, you lose everything,” Kingsley said. “You lose all your possessions, your … credit score goes down, all your bills go unpaid … The benefit (of working) far outweighs the negatives.”

No statewide data available

How many prisoners participate in work release statewide? Corrections officials don’t consistently keep track, Hardtke said.

The department’s public data dashboards show prisoner demographics, recidivism rates and enrollment in educational or treatment programs, among other things. Employment numbers are not included.

“What’s important from a correctional standpoint is that you know where everybody is,” Hardtke said, adding that such jobs data “would need to be compiled from multiple sources.”

The latest numbers Wisconsin Watch could find are from 2024. Responding to a Legislative Fiscal Bureau request for a report on state prisons, the department’s research team manually calculated that 781 people had work release jobs in July 2024, Hardtke said.

Asked for a current figure, Hardtke said “that number is not something we have readily available nor is it something you could accurately pull from a single source or document.”

Officials also don’t track how many people are eligible for work release. As of Oct. 31, 2,778 Wisconsin prisoners were at the department’s lowest custody level.

Several neighboring states routinely track how many people have work release jobs or are eligible for them. Of the 11 other Midwestern states Wisconsin Watch asked, seven responded.

- Four said they track the number of participants but not the number of people eligible: Minnesota (186), Missouri (202), North Dakota (13) and South Dakota (183).

- Iowa officials said they track eligibility (418) but don’t track how many people have work release jobs.

- Nebraska officials said they track both: 378 were eligible, and 374 were working.

- Officials in Michigan said they don’t offer work release.

Prisoner pushes for more jobs

In July, Kingsley wrote to Warden Clinton Bryant, who oversees the men’s minimum-security centers, asking him to add 100 more work release jobs.

“By writing you first, I hope that changes can be made. Changes that not only benefit the guys here or at other centers, but also the DOC and the state as a whole,” Kingsley wrote. Adding those jobs would generate $75,000 a month in room and board payments, along with state taxes, he wrote.

Bryant responded that Winnebago Correctional Center “collaborates with community employers on a daily basis” and that prison officials can’t require employers to hire anyone.

Jobs aren’t particularly hard to find near Winnebago Correctional Center. Like the rest of the state, Winnebago County faces a growing worker shortage as baby boomers retire. Prisoners aside, the share of the county’s population that’s working or actively looking for work has fallen 7.4% since 2000, according to the Department of Workforce Development.

Winnebago County’s unemployment rate — which excludes people in prison — was among the lowest in the state in 2024, according to DWD data.

Wisconsin’s labor market has softened since last year but remains strong, said Dave Shaw, a regional director of the Department of Workforce Development’s Bureau of Job Service, which manages the state website that matches employers and job seekers.

“It’s still fairly easy to find work, and there are a lot of jobs out there,” Shaw said.

It can be harder to find a job with a criminal record, but Shaw said his team works with a variety of companies that are “interested in giving individuals a second chance” to get back in the workforce.

“There are employers all around the state who are willing to do that,” Shaw said, noting that the state offers tax credits and free insurance to employers who hire people with criminal records.

When Kingsley contacted Bryant again, urging the department to establish minimum job placement rates for work release centers, the warden ended the conversation.

“My office addressed these matters and provided you a response,” Bryant wrote. “No further correspondence on these matters will be addressed by my office.”

So Kingsley took the issue to the State Capitol. In May, Republican lawmakers introduced legislation that would give bonuses to probation and parole officers who increase the employment rate among the people they supervise. Kingsley asked them to do the same for work release centers.

All of the bill’s authors and cosponsors either declined Wisconsin Watch’s request for comment or did not respond.

As of publication of this story, Kingsley has yet to receive a reply.

Help Wisconsin Watch report on work release

Have you served time and qualified for work release? Or do you know someone who has? We’d like to hear about your time working or waiting for work. We’re also looking for any other story ideas about jobs and education behind bars. And we’d like to hear perspectives from those who have hired people with criminal records. Click here to fill out a short form. Your answers will not be published without your permission.

Natalie Yahr reports on pathways to success statewide for Wisconsin Watch, working in partnership with Open Campus. Email her at nyahr@wisconsinwatch.org.

This article first appeared on Wisconsin Watch and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.![]()

If you think stories like this are important, become a member of Urban Milwaukee and help support real, independent journalism. Plus you get some cool added benefits.

Wisconsin’s DOC is far behind other states in most areas. Not tracking Work Release data is a poor excuse for not allowing more Inmates to Work.

DOC is contributing to recidivism.

Racial Profiling & so called War on Drugs created Mass Incarceration.

Overcrowded Prisons are hard on Inmates & Staff.