Is Raising the Minimum Wage Good Policy?

Or just good politics? Let's consider the data for both.

In 1938, in the midst of the Great Depression, the federal government introduced the minimum wage as part of the New Deal’s Fair Labor Standards Act. The act required employers to pay their employees at least 25 cents an hour.

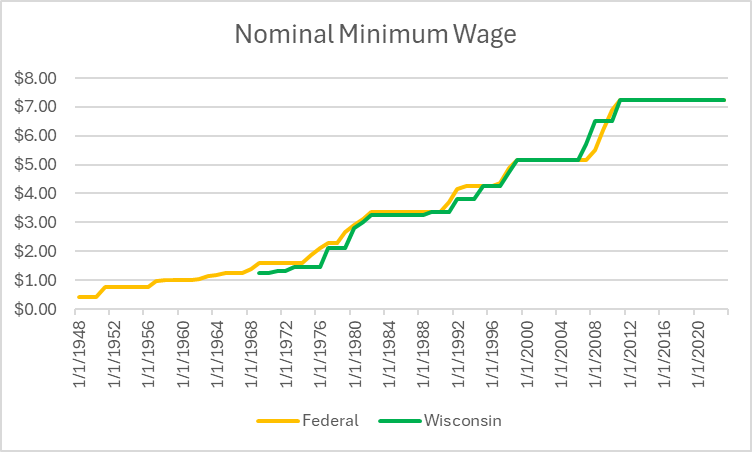

In 1968, Wisconsin added its own minimum wage, shown in green in the graph. Although the state minimum started as less than the federal minimum, it has mostly tracked the federal wage.

Today’s $7.25 federal (and Wisconsin) minimum wage was adopted in 2010 and has not been raised since.

The two lines in the above graph show the nominal value of the state and federal minimum wages while ignoring the effect of inflation. A given amount of dollars bought a lot more goods and services in 1948 than the same amount dollars in 2024.

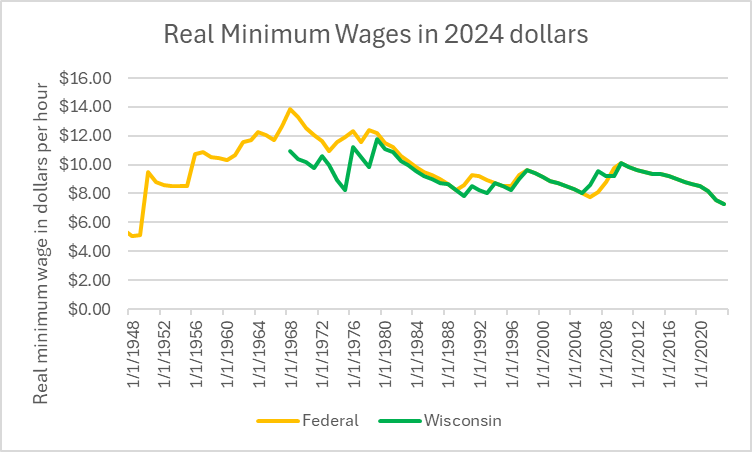

For the next graph, I converted the nominal value of the minimum wages into their equivalent values in 2024 real dollars. In real terms the real value peaked in 1968. Its nominal value of $1.25 was worth $13.84 in today’s dollars.

In the years following 1968, the nominal value of the minimum wage increased from time to time, but not enough to keep up with inflation. It is worth noting that in 1968 Lynden Johnson was president. Raising the minimum wage was part of his War on Poverty.

The historic view of the minimum wage by economists was that it was not an effective tool against poverty. In this view, it would increase the income of those poor people fortunate enough to keep their jobs, but their gain would be offset by others who would lose their jobs and become even poorer. This understanding was supported by standard economic theory: as the price of something (in this case labor) goes up demand for it goes down.

The first serious challenge to this belief came from a study by economists David Card and Alan B. Krueger. On April 1, 1992, New Jersey’s minimum wage increased from $4.25 to $5.05 per hour, while Pennsylvania’s minimum remained the same, at $4.25. Card and Krueger reported that:

Our empirical findings challenge the prediction that a rise in the minimum reduces employment. Relative to stores in Pennsylvania, fast food restaurants in New Jersey increased employment by 13 percent. We also compare employment growth at stores in New Jersey that were initially paying high wages (and were unaffected by the new law) to employment changes at lower-wage stores. Stores that were unaffected by the minimum wage had the same employment growth as stores in Pennsylvania, while stores that had to increase their wages increased their employment.

Following the release of the Card and Krueger study, there were numerous similar studies of similar pairings matching jurisdictions increasing their minimum wage against neighboring jurisdictions that left it alone. Some, like Card and Krueger, found increased employment, some found decreased, and others found no significant effect.

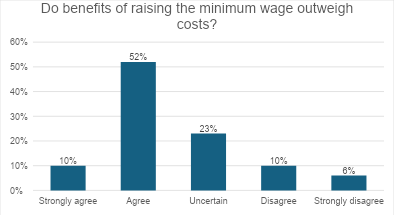

In 2013, the Kent A. Clark Center for Global Markets at the University of Chicago asked a panel of academic economists to respond to the following statement: “The distortionary costs of raising the federal minimum wage to $9 per hour and indexing it to inflation are sufficiently small compared with the benefits to low-skilled workers who can find employment that this would be a desirable policy.” Here is the response weighted by the confidence of the economists. It’s worth noting that the $9 wage translates to $12.19 per hour today.

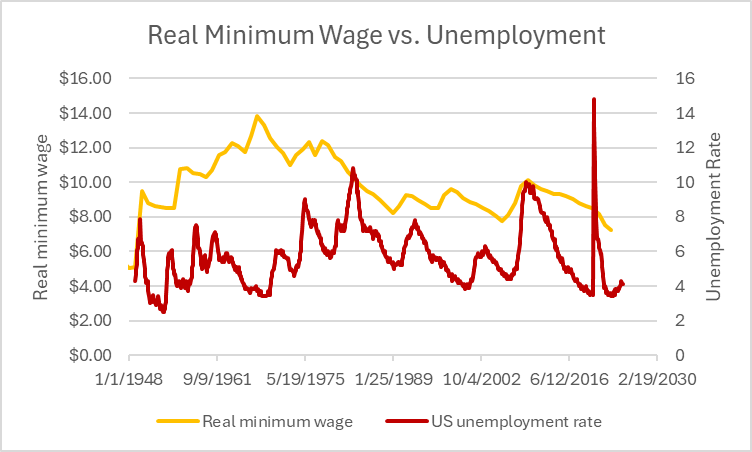

The next graph plots the result of a different approach to the issue of whether the benefits outweigh the costs. It compares the real minimum wage over time against the unemployment rate. In the early post-war period, the wage was steadily increased until its peak of $13.84 in 1968. Yet there is no evidence of a noticeable increase in unemployment.

Following that peak, the real minimum wage was allowed to lag inflation, effectively decreasing its value. If anything, unemployment increased as the real minimum wage decreased.

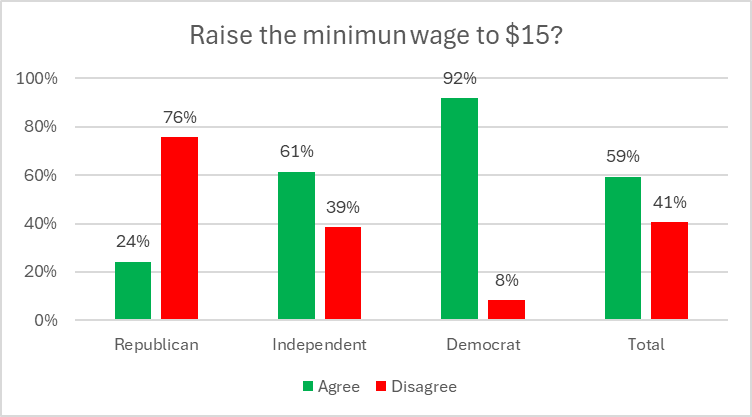

In its August 2020 survey, the Marquette Law School poll asked a sample of Wisconsin voters whether the minimum wage should be raised to $15 per hour. The next graph summarizes the results according to the respondents’ political orientation, using green for those agreeing and red for those disagreeing. 59% of those with an opinion supported the proposal.

An overwhelming majority of Democrats supported the proposal, as did a smaller majority of Independents. A majority of Republicans opposed it. Even so, a quarter of Republicans were in support.

For Democrats this means that raising the minimum wage should be a very attractive issue: one that unites one’s base, while splitting the opposition’s supporters.

The evidence points to a conclusion that raising the minimum wage is good policy. For Democrats, it is also good politics.

Correction: the column originally stated that the results of the Clark Center’s panel of academic economists were released last year. It was actually released in 2013.

If you think stories like this are important, become a member of Urban Milwaukee and help support real, independent journalism. Plus you get some cool added benefits.

Data Wonk

-

Life Expectancy in Wisconsin vs. Other States

Dec 10th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Dec 10th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

-

How Republicans Opened the Door To Redistricting

Nov 26th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Nov 26th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

-

The Connection Between Life Expectancy, Poverty and Partisanship

Nov 21st, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Nov 21st, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

“The evidence points to a conclusion that raising the minimum wage is good policy. For Democrats, it is also good politics”.

I guess “bravo” Democratic Governor Jim Doyle who “compromised” with the Republican Legislature and agreed on a bill that would stop Wisconsin municipalities from raising their wages in the future, offering a one-time raise of the state’s minimum wage instead. (Some WI cities were trying to raise their minimum wages on their own in 2004, Republicans wanted to stop it). The state minimum wage was raised to $5.70 but that raise was eclipsed by the increase in the federal minimum wage of $7.25 in 2009. This makes the JIm Doyle “compromise” seem more like a ball and chain for low wage WI workers. Good work Democrats!