Wisconsin is Now Midwest Leader In Deadly Police Encounters

A sudden surge follows a period where Wisconsin had lowest-in-the-nation rate. What changed?

This story was produced and originally published by Wisconsin Watch, a nonprofit, nonpartisan newsroom. It was made possible by donors like you.

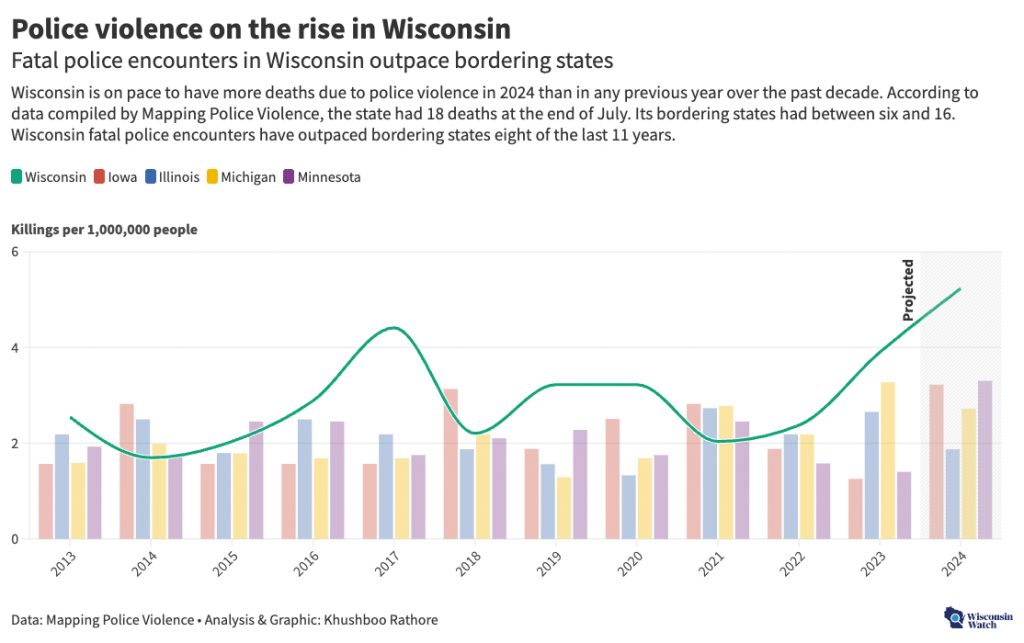

Deadly police encounters in Wisconsin were up last year and are on track this year to exceed the modern record of 26 deaths set in 2017.

The increase comes after Wisconsin Watch and The Badger Project reported two years ago that Wisconsin’s rate of police killings ranked among the lowest in the nation over the past decade. In the past two years the rate has risen, particularly compared with neighboring states.

Wisconsin Watch conducted its own count of fatal use-of-force incidents because the state Department of Justice’s tracking falls short and is updated only four times a year. The department’s use-of-force tally does not reflect police incidents involving restraints, “non-lethal” force and confrontations that ended in suicide.

Wisconsin Watch also found cases in which law enforcement violated its own de-escalation protocols and resorted to deadly force in ways that experts say contradict long-established best practices — all with little accountability.

In at least one death last year, authorities used a medically discredited condition that still appears in state training materials to justify forcibly restraining someone during a struggle.

Tracking every police killing or injury remains difficult, and efforts to tighten oversight and accountability have largely stalled in the state Legislature.

Local district attorneys have determined virtually every police use-of-force case was justified. But the increased frequency of fatal encounters has prompted law enforcement accountability advocates to call for more state oversight.

“Oftentimes the DA looks at just that immediate piece where the officer felt their life was in danger,” said Amy Watson, a mental health researcher at Wayne State University who has studied fatal police encounters, “but doesn’t usually consider the steps before that created that situation.”

Russell Beckman, a retired Kenosha detective turned policing reform activist, said he fears police killings now carry less stigma and that the legal system allows officer safety to trump public safety.

“A shoot can be legal — justified — a legal justified shoot,” he said. “But that doesn’t mean it was necessary.”

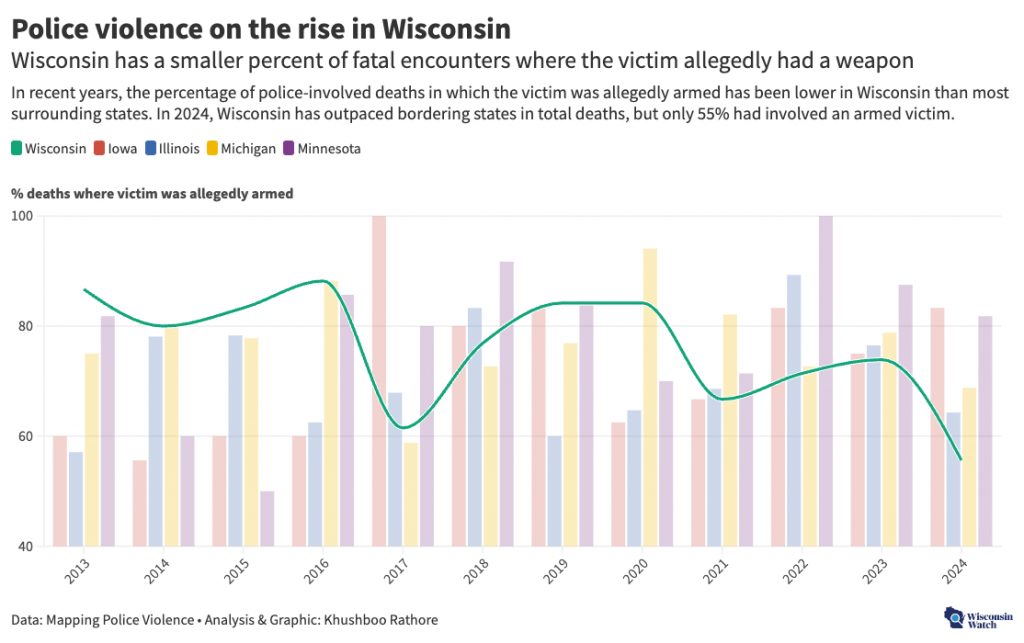

The state’s largest police union doesn’t dispute the rising death count but says police are mostly responding to people who are armed or thought to be armed — threatening officers or bystanders.

“I don’t think there is a good explanation,” said Jim Palmer, executive director of the Wisconsin Professional Police Association.

“What we’ve seen over the last several years is an increased proportion of individuals that are involved in fatal police encounters that confront officers with a weapon — whether it’s a firearm, or a knife, or a sword or an edged weapon.”

Wisconsin Watch’s count of at least 19 fatal encounters matches figures from Mapping Police Violence, a research collaborative that has tracked such data since 2013. Over that 11-year time frame about three in four fatal encounters in Wisconsin involved a subject with an alleged weapon, according to a Wisconsin Watch analysis of the collaborative’s data.

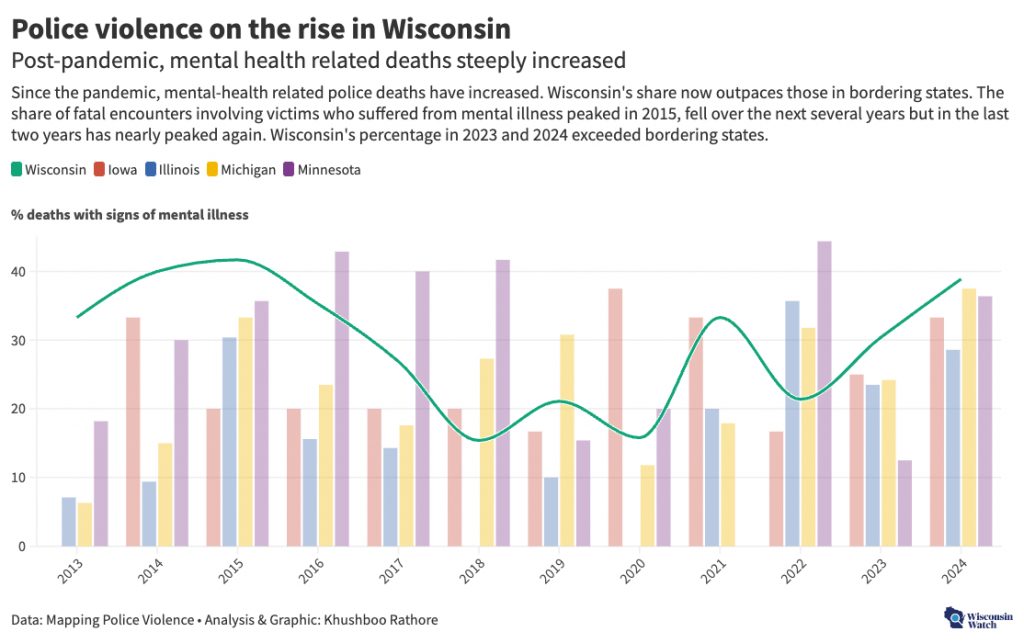

But since the pandemic the percentage of cases involving a weapon has been lower than in neighboring states, while the percentage involving a mental health crisis has increased, the analysis found.

The data include deaths DOJ has not tracked as caused by police use of force. Some subjects killed were unarmed, and some fatalities were not shootings, leading the coroner to classify the death as accidental, allowing police and first responders to escape deeper scrutiny.

“There’s been a lot of concern about medical examiners and coroners classifying deaths in custody as accidental and downplaying the potential role of the various interventions that were undertaken prior to the death,” said Dr. Paul Applebaum, Columbia University professor of psychiatry, medicine and law.

‘I’m in fear of my life’

When responding officers tased and then sat on a handcuffed 26-year-old Kaukauna man suspected of killing his wife last October, he told officers: “I’m in fear of my life.”

An officer then sat on his back for at least six minutes as others attended to the victim in the next room. Medics injected the powerful sedative ketamine with a syringe. His breathing became labored. Once loaded into the ambulance, he was declared unresponsive with no pulse. He was pronounced dead at the hospital.

Police and medics likely didn’t realize their actions risked killing Eric VanSyoc, said experts who examined reports and investigatory files Wisconsin Watch obtained through public records requests.

“I suspect that their training was inadequate to warn them both about the dangers of prone restraint and about the risks associated with sedation with ketamine,” said EMS trainer Eric Jaeger, who has helped other states improve safety protocols.

Yet Outagamie County District Attorney Melinda Tempelis wrote that responding officers in Kaukauna used “an appropriate amount of force to prevent the imminent death or great bodily harm to themselves or others.”

A Kaukauna police statement on social media said VanSyoc experienced a “medical episode” but did not mention sedation or restraints that followed the tasing. The death, ruled accidental by the county coroner, does not appear in the state’s list of police use-of-force deaths.

‘You’re gonna get bit’

The majority of 2024 in-custody deaths involved shootings of suspects deemed threatening. In some cases prosecutors ruled such force justified even though officers disregarded de-escalation best practices.

The Rice Lake Police Department’s crisis intervention protocols call for attempts at de-escalation before resorting to deadly force. They instruct officers not to “argue, speak with a raised voice or use threats to obtain compliance.”

Medics had already treated the stabbing victim for injuries to her upper arm when police used a key to enter Veitch’s apartment. An officer had threatened Veitch with a barking police dog if he didn’t surrender.

“You need to come out or you’re gonna get bit!” an officer shouted from the hallway.

Veitch, who was living with a mental illness, refused and retreated into his bedroom.

“He thought he was a prophet. That’s how far into religion he was,” his father later told Wisconsin Watch.

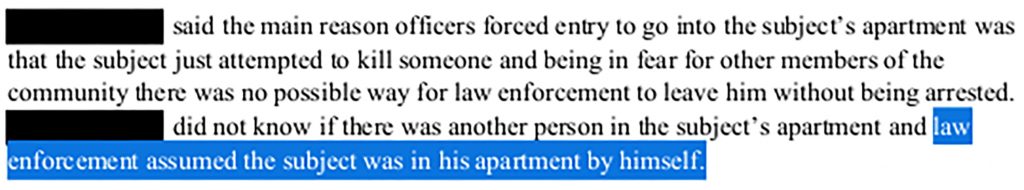

Law enforcement officers broke down the bedroom door where 50-year-old Zachary Veitch was hiding after slashing at a fellow tenant with a knife and fleeing into his own apartment. The unnamed officers who killed him later admitted they had no reason to believe anyone else was in the apartment, raising questions why they rushed into the mentally ill man’s apartment, resulting in a deadly confrontation.

Thirty seconds after officers entered the apartment and released the police dog, they forced Veitch’s bedroom door open. He lunged with a knife, and officers shot him dead in his kitchen, bodycam footage shows.

A retired police officer who reviewed the redacted investigation questioned the rush to use deadly force against a man alone in his own apartment.

“I didn’t see that they attempted to establish any kind of a dialogue,” said John Wallschlaeger, who retired from the Appleton Police Department and has long trained Crisis Intervention Teams across Wisconsin.

Radio chatter captured on the bodycam indicates that sheriff’s deputies were bringing a riot shield to the apartment complex for the responding officers.

“They didn’t wait for the shield,” Wallschlaeger added. “Even though the shield was en route, they didn’t wait for it.”

The Rice Lake police chief and the Barron County sheriff later announced that an unnamed use-of-force panel “made up of various law enforcement professionals” concluded the actions of a deputy and officers involved fell within the sheriff’s “department policy and procedures.”

Its reasoning remains unclear. Barron County Sheriff Chris Fitzgerald told Wisconsin Watch their findings “were not in written form.”

Barron County District Attorney Brian Wright said police acted reasonably when they shot and killed 50-year-old Zachary Veitch, who had a knife in his hand when officers forced open his bedroom door. (Barron County District Attorney’s Office)

Barron County District Attorney Brian Wright ruled that officers acted reasonably and commended them for protecting themselves and other residents in the apartment complex.

“Officers were confronted with the urgency of taking Veitch into custody before he harmed anyone else,” he wrote. That contradicted the official report in which officers said they assumed he was alone in his apartment.

The suspect’s father, who surveyed his son’s blood-spattered apartment days later, said he can’t understand the officers’ tactics.

“I know he would have been able to be talked down,” Gary Veitch told Wisconsin Watch. “It may have taken a few minutes. But where were they going, you know? They had him.”

DOJ records Veitch’s death as related to use of force. But authorities have withheld the names of the police officers and sheriff’s deputy who fired their weapons. Investigators cited threats made by the dead man’s son against officers captured in recorded jailhouse phone calls following news of the fatal shooting.

Craig Futterman, a clinical professor of law at the University of Chicago and founder of the Civil Rights and Police Accountability Clinic, said de-escalation protocols matter only when enforced.

“Unless there are consequences for failing to de-escalate, a lot of the policies or practices or training may not be worth much,” he said.

‘I’m on drugs!’

A nationwide Associated Press investigation into more than a thousand deaths after police subdued someone with force not supposed to be lethal found it common for agencies to withhold medical records that contain evidence of potential missteps.

In Wisconsin’s Lafayette County last February at 1 a.m., an agitated man in his underwear cursed and shouted “I’m on drugs!” and fought with officers who tried to subdue him in the street.

A police officer hit Gregg Marcotte with a Taser at least twice. A ground scuffle ensued. The 44-year-old man was later found to be unresponsive in the ambulance and declared dead at the hospital.

Whether use-of-force protocols were followed is unclear. State investigators heavily censored video footage of the melee with police, Marcotte’s cause of death and the treatment he received by paramedics.

The autopsy said Marcotte likely died from a mix of a heart attack, high blood pressure, drug use, blunt chest trauma and prone restraint exacerbated by his fight with police.

Wisconsin law enforcement officials withheld key details — including the cause of death — of 44-year-old Gregg Marcotte, who died Feb. 12, 2024, following a prolonged struggle with police officers and sheriff’s deputies on a public street in downtown Shullsburg, Wisconsin, where he lived.

“The ruling is this was an unfortunate accident,” wrote Lafayette County Coroner Linda Gebhardt.

Dr. Victor Weedn, a forensic pathologist with expertise in arrest-related deaths, questioned that conclusion, saying it overly emphasized the methamphetamine in Marcotte’s system.

“I believe this is probably a prone restraint cardiac arrest / metabolic acidosis death, and I would rule the death a homicide,” wrote Weedn, a former chief medical examiner for the state of Maryland.

He reviewed the state Division of Criminal Investigation’s investigation and medical examiner’s reports at Wisconsin Watch’s request. He cautioned that he would need additional information, specifically the decedent’s heart rhythm, to make a more definitive ruling.

Wisconsin Department of Justice officials completely blurred out images of 44-year-old Gregg Marcotte during his fatal Feb. 12, 2024, confrontation with police in downtown Shullsburg, Wisconsin, citing privacy concerns. The editing makes it impossible to see whether use-of-force protocols were followed in the lead-up to the man’s death. (Wisconsin Department of Justice)

Wisconsin a regional leader in fatal encounters

Kaul, the state’s elected top law enforcement officer, asked about the increase in fatal police encounters during a June appearance at the Appleton Police Department, said officers are operating in a state whose lax gun laws make weapons easily available.

“Somebody can literally sell a gun out of the trunk of their car to a perfect stranger,” Kaul said.

The increase in fatal police encounters does not correspond with an increase in violent crimes. An analysis of DOJ crime data shows that violent offenses were up in 2021 but have declined each year since.

Advocates for police reform have expressed alarm at the rising death toll and transparency gaps in Wisconsin.

Illinois, with twice the population, has seen a sharp decrease in fatal police encounters with at least 16 so far this year compared with at least 19 in Wisconsin.

Advocates for police reform point to the Chicago model that in 2016 empowered the Civilian Office of Police Accountability to investigate misconduct complaints and in-custody and arrest-related deaths.

Illinois lawmakers later enacted laws to harmonize use-of-force policies, require officers to intervene if they witness excessive force and make police misconduct records easily available.

“When officers see fellow officers lose their jobs, lose money, lose pay over their failure or refusal to abide by core de-escalation policies — you change,” said Futterman, the University of Chicago law professor.

A 2021 Illinois law requires reviews of the totality of circumstances rather than the final seconds when police officers feel threatened and use deadly force.

Fatal police encounters remain a nationwide challenge with more than 1,350 deaths last year and 2024 on pace to match that amount.

The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine convened an expert panel to investigate and consider recommendations to reduce such encounters.

A 2000 federal law requires in-custody deaths to be reported to the U.S. Department of Justice. But officials with the department’s Bureau of Justice Assistance, which collects those figures, say inconsistent reporting leaves them with data too incomplete to publish frustrating efforts to fully grapple with the issue.

‘Excited delirium’ remains on the books

Official data are skewed in states like Wisconsin, where deadly encounters involving Tasers, restraints and other so-called non-deadly means are often not tallied as related to use of force.

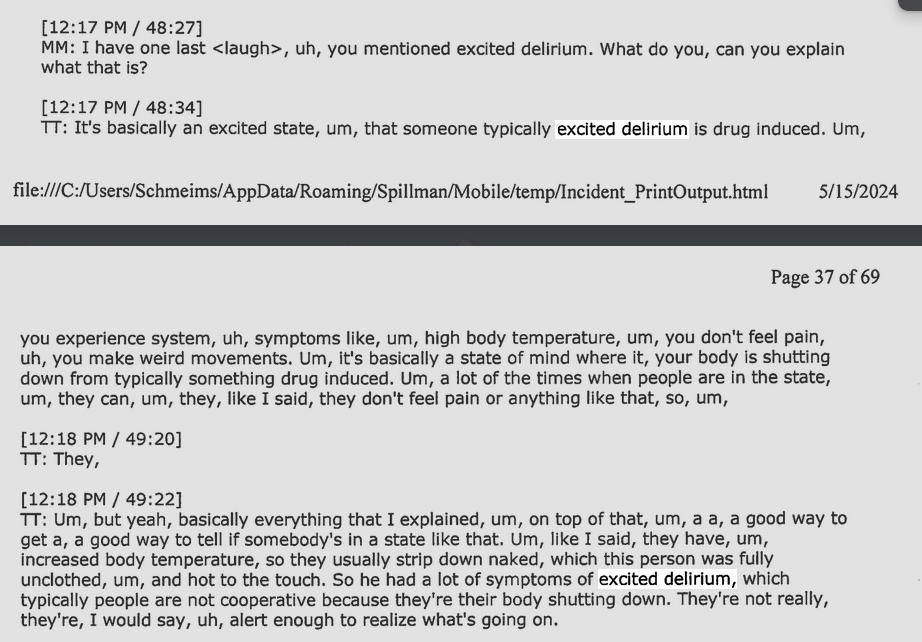

For decades, forensic experts say, police and paramedics have cited “excited delirium” — a widely discredited diagnosis blamed for justifying excessive force in cases across the nation.

But even some de-escalation advocates continue to defend the concept behind it: that a subject’s death is inevitable without rapid intervention. It remains a key component in crisis training in Wisconsin.

“The dominoes are already falling, but we can’t see it,” said Wallschlaeger, the retired Appleton officer and crisis intervention team trainer. He described “medically significant situations” in which an agitated subject is fighting with police. “And so we have to err on the side of caution and activate EMS.”

That line of thinking can lead to responses including sedation and restraints, which if not applied properly can prove deadly.

Kaukauna police officers on Oct. 14, 2023, used Tasers and restraints and had medics sedate an agitated murder suspect with ketamine before he died. Officers and the DA later said he’d been suffering from “excited delirium,” a widely discredited pseudo-condition that remains a part of crisis intervention training in Wisconsin police manuals.

The conflation of force with emergency medical care frustrates other crisis intervention experts who see mixed messages in the training to respond to agitated and mentally ill subjects.

“On the one hand, you’re training officers to slow things down, use time, use distance,” said Watson, the Wayne State mental health researcher. “But then if someone’s really, really agitated, ‘Oh, you need to tackle them and have EMS sedate them.’ Folks with serious mental illness tend to be at higher risk of having bad responses to that type of sedation.”

That was likely a factor when officers responded to a welfare check for a missing woman and found a combative and delusional VanSyoc in his Kaukauna home in October 2023. The medical examiner found an acute mix of drug toxicity coupled with the restraints and use of the Taser contributed to his death.

Tempelis, the district attorney, cleared the police in his death, stating “it is clear VanSyoc was experiencing a state of excited delirium which in and of itself can cause acute distress and sudden death due to the methamphetamine and designer drugs he consumed prior to officers’ arrival.”

EMS trainer Jaeger reviewed the reports and was critical of the DA’s reasoning and conclusions.

“‘Excited delirium’ is very clearly a flawed concept that should be removed both the name and substance anywhere it appears,” he said.

Major medical organizations in the United States have now rejected it as a scientific concept.

State officials say they are working to remove the term “excited delirium” from law enforcement manuals. Yet even recently updated materials refer to a “freight train to death,” a similar concept that DOJ’s head of police training and standards said conveys the urgent need to attend medically to an agitated person.

Kaukauna Police Chief Jamie Graff defended his officers’ assessment and response in the VanSyoc incident.

“Our department training is consistent with the standards set forth by the Wisconsin Training and Standards Board,” he told Wisconsin Watch.

Jaeger, who helped update New Hampshire protocols that now prohibit sedating subjects lying on their stomachs, and another independent expert said a factor not mentioned in official documents may have contributed to the death: forcing VanSyoc to lie prone with an officer’s weight on his back even after he stopped struggling.

“It’s been well known for many decades that you’re not supposed to keep people lying on their stomach,” said Justin Feldman, a social epidemiologist at Harvard University and researcher with the Center for Policing Equity. “You’re supposed to, at minimum, put them on their side.”

The Wisconsin Department of Justice categorizes deaths as arrest-related — rather than from use of force — if suspects are restrained, shocked with Tasers or even sedated in ways medical experts consider potentially dangerous.

DOJ doesn’t publish stats on when mental illness was evident in an encounter, but Mapping Police Violence found that the deceased person exhibited signs of a crisis in at least 14 of Wisconsin’s at least 43 fatal police encounters since the beginning of 2023.

State public health officials referred questions to the National Alliance on Mental Illness, which trains law enforcement in crisis intervention to improve public safety.

Emilie Smiley, program director of NAMI Wisconsin, said she couldn’t comment on specific incidents.

But she said broadly: “There are situations where law enforcement are not necessarily the best fit for responding to a mental health crisis,” but sometimes law enforcement is necessary.

DOJ oversight lacking

State law has since 2021 required the Department of Justice to publicly report in-custody, arrest-related and use-of-force deaths. But the department’s dataset — which relies on law enforcement agencies to report incidents — remains incomplete and often misleading, obscuring precise trends.

The online database tabulates reports by agency, meaning multiple entries could describe the same incident, depending on how many agencies responded.

The Fond du Lac Sheriff’s Office logged one fatal incident in which a suspect shot himself during a shootout with police as a use-of-force injury. But Fond du Lac city police reported it as an arrest-related death. Both appear separately in DOJ’s database.

Some fatal police shootings weren’t counted at all. On Sept. 13, 2022, Milwaukee police shot and killed 40-year-old Sherman D. Solomon after responding to a call of shots fired in a neighborhood.

The Milwaukee Police Department summarized the incident in a six-minute video, but it does not appear in the state’s tracker.

DOJ spokesperson Gillian Drummond would not comment on the omission, nor would she say how the agency evaluates its use-of-force data or views the increasing trends.

“We’re following state statutes,” she said. “The data is online for the public to review.”

The American Civil Liberties Union, which lobbied for the state use-of-force reporting law, said DOJ is falling short of its duty to accurately track police violence and publish accurate results.

“It’s really concerning when there are clearly incidents that would fall under the requirements of statutory reporting, and they don’t show up,” said Amanda Merkwae, advocacy director for ACLU Wisconsin.

“It just seems like part of the pattern of individual law enforcement agencies fighting efforts at transparency, as much as they can.”

Calls for more oversight

Retired Kenosha detective Russell Beckman, a police reform advocate, said he’s disturbed by the rise in deadly encounters involving police. He partly blames a police culture that relies on Tasers and firearms over negotiation. (Russell Beckman)

Advocates for more police oversight argue that today’s officers are too quick to fire a Taser or service weapon when feeling threatened.

Beckman, the retired Kenosha detective, said he faced many scenarios over 30 years that required using physical force to bring combative suspects under control.

“I think about all the times where I could have legally shot somebody — but I didn’t,” he told Wisconsin Watch. “Because I waited until the last possible instance. So I could try to resolve the situation and de-escalate it. And that’s the attitude of most cops.”

He worries that’s starting to change.

Sen. Chris Larson, D-Milwaukee, faced heavy criticism after suggesting that some politicians shield officers who are “quick to pull the trigger and quick to take a life” by supporting a Republican bill that would have limited avenues to prosecute police officers.

“Everyone makes their own political decisions, but man, it seems like a rough one to defend,” Larson said on the Senate floor.

Republicans publicly rebuked Larson the next day.

“His comments show that he has no understanding about what it is like to be in a position where you might have to take a life in self-defense,” Sen. Jesse James, R-Altoona, a former police officer, said in a press release.

A larger role for state attorneys?

A 2014 state law requires an outside agency to investigate fatal encounters with police. The district attorney of that county must review the findings and decide whether police acted lawfully.

The 2016 shooting of Sylville Smith sparked violent unrest across Milwaukee and resulted in the past decade’s only prosecution of a Wisconsin police officer due to on-duty use of deadly force, according to Mapping Police Violence data. A jury later acquitted ex-officer Dominique Heaggan-Brown of reckless homicide.

La Crosse County District Attorney Tim Gruenke, a veteran prosecutor, said he supports DOJ attorneys reviewing deadly force incidents rather than local prosecutors.

“It can put the DAs in a position where they’re having to make judgments on people that they know that they’ve worked with, they might have opinions about,” Gruenke told Wisconsin Watch.

Gruenke said he has investigated about five police shootings in his multi-decade career that he considered clear-cut with no charges warranted. He said he intends to send the next one he sees to a special prosecutor outside La Crosse.

“I have the option of asking DOJ — there’s no requirement that they take it,” Gruenke said. “Going forward I’ll probably have another DA’s office just look at the ones in my county.”

DOJ’s Drummond wouldn’t say whether her agency would accept responsibility for investigating and legally reviewing such incidents but noted that it would struggle to do so at current staffing levels.

“There would need to be resources in the form of additional assistant attorneys general to ensure that we were able to meet the demand,” she said.

Legislation sought panel to review police incidents

AB 112 — introduced by Wisconsin Republicans and then-Sen. Lena Taylor, D-Milwaukee, in 2021 — would have created a statewide panel to review deaths and serious injuries at the hands of police.

Gruenke likens it to the National Transportation Safety Board, which does not rule on culpability of serious crashes but dissects what happened and lessons learned.

“Even if the shooting was legally permissible, even if an officer does something exactly the way they were trained,” Gruenke said, “it’s still something that we should look at to say, ‘Well, are there ways that could have been avoided?’”

Some critics worried the committee’s findings could be used in federal civil or criminal proceedings in ways state lawmakers didn’t intend, said Scott Kelly, an aide to Sen. Van Wanggaard, R-Racine, who pushed the bill.

“It is not on our immediate agenda to introduce next session,” Kelly said.

Wisconsin Watch data reporter Khushboo Rathore contributed reporting.

The nonprofit Wisconsin Watch (www.WisconsinWatch.org) collaborates with WPR, PBS Wisconsin, other news media and the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by Wisconsin Watch do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.

I attended Milwaukee Ex-Police Officer, Dominique Heaggan-Brown’s, trial for the Reckless Homicide of Slyville Smith.

After Smith was already shot once: Video clearly shows Smith lying on his back toss his gun over the fence. Then Officer Heaggan-Brown fired his gun killing Smith.

Result: Officer Heaggan-Brown was Aquitted!.