Seclusion and Restraint of Kids in Wisconsin Schools

Nearly 13,000 incidents reported in 2021-22. ‘Districts should not torture children.’

A seclusion room in the Fox Valley school that Streck taught at and the her son attended. A sign on the door states the room is a “safe space.” (Photo courtesy Stephanie Streck)

Melanie Becker’s son isn’t restrained by school staff or secluded in a room away from his classmates to the same extent that he once was, but his past experiences continue to color his perception of school.

“I feel like in some part of my, like, deep subconscious I’m afraid of school now,” he said.

The 14-year-old, who is autistic and deals with other challenges including depression and anxiety, was suspended on his first day of kindergarten in 2015 for locking himself inside a restroom with another student. His mother said he was scared and wanted to hide, adding that he didn’t mean any harm and that the other student just happened to be in the restroom.

“When other children would come in and out of the room, he would get all excited and hyper,” said Becker, who lives in western Wisconsin. In response, staff put the 5-year-old in a padded room and blocked the door with a gym mat.

“It was supposed to make him calm down but it did the opposite. It just made him more and more mad,” Becker said.

One month into kindergarten, he was transferred by the school to a school in Minnesota through an out-of-district placement. His mother said he was still restrained and secluded at the new school, but it happened less frequently.

After crossing the state line for school for two years, Becker’s son returned to the Hudson School District for the second and third grades.

“It’s just the same stuff started again, constantly putting him in that room for stuff,” Becker said.

Once, Becker said, her son forgot his jacket when his class was going outside. After being told that he couldn’t get it, he tried to run back into the school building and was secluded for not listening to staff.

“It was just that kind of stuff where it comes down to kind of like a power struggle all the time with these autistic kids,” Becker said. “Their brains are wired differently.”

For decades, advocates have sought to limit the use of seclusion and restraint in schools due to the mental and physical effects on children, many of whom are elementary school students with disabilities. Yet the practices continue to be used across Wisconsin, and in the recent legislative session some lawmakers sought unsuccessfully to loosen restrictions meant to protect children.

In the 2021-22 school year, Wisconsin schools reported almost 6,000 seclusion and 7,000 restraint incidents to the state Department of Public Instruction. Students with disabilities were disproportionately involved in the incidents, continuing the trend from previous reports.

Families and disability rights advocates say more work needs to be done to limit the use of seclusion and restraint throughout the state. Among their concerns are overuse of the practices, inadequate funding for special education in Wisconsin, whether the state Department of Public Instruction could be doing more to reduce the use of seclusion and restraint in schools, and the recent legislative efforts.

Where state law stands on seclusion and restraint

Restraint and seclusion are meant to be measures of last resort for dealing with students who exhibit disruptive behavior, yet the practices remain widespread.

Wisconsin adopted its first law to regulate seclusion and restraint use in 2010 — following public hearings in the state Capitol that included testimony about students being locked in rooms alone or injured from restraints. Around the same time, Congress started examining the issue due to a GAO report that found some students had died as a result of the practices. Incidents similar to those described in the GAO report have occurred in Wisconsin. A 2009 report by statewide advocacy groups detailed the death of a 7-year-old girl in 2006 due to injuries sustained from restraint use in school.

Wisconsin state law was updated in 2019 to further restrict the use of seclusion and restraint and to require schools to report data about the practices to the state Department of Public Instruction.

Jeff Spitzer-Resnick, a civil rights attorney and longtime advocate for limiting seclusion and restraint use in Wisconsin, said the new laws have helped stop the worst cases that used to occur in Wisconsin schools.

“As someone who’s been following this and representing children for decades, I think the really egregious examples are gone,” Spitzer-Resnick said. “We no longer have seclusion rooms that would shock the conscience like we used to — with insulation coming out of the walls. We no longer have kids tied, locked in rooms so long they’re urinating and defecating in the rooms. … We’ve gotten the really horrific stuff out.”

Mary Cerretti, an advocacy specialist with Disability Rights Wisconsin, also said the laws have helped significantly with limiting the worst cases, but said she still sees some really bad cases. She also added that sometimes students and families report an instance of seclusion or restraint, but schools deny it happened.

Spitzer-Resnick said he and other advocates knew while working to get the first bill passed that the real challenge to eliminating seclusion and restraint would be getting sufficient funding for support staff and training. He said proper support would help accomplish the positive goal of figuring out “how do we teach appropriate behavior,” and “how do you deal with difficult, challenging behaviors.”

Fifteen years after the passage of that law, Spitzer-Resnick said the challenge hasn’t been met because the Legislature refuses to allocate state money to adequately support schools and special education.

DPI’s role in limiting seclusion and restraint practices

Advocates seeking to limit seclusion and restraint expressed concerns about whether enough is being done by the Department of Public Instruction to keep schools accountable.

According to DPI spokesperson Chris Bucher the agency analyzes the data, identifies schools with high rates of seclusion and restraint and provides support to those schools.

The agency has identified three trends: seclusion and restraint incidents disproportionately include special education students with Individual Education Programs (IEPs); the incidents almost exclusively happen on the elementary level and they involve a relatively small number of students.

DPI’s report on the 2021-22 school year shows a total of 1,920 students — 79% of whom were students with IEPs — were involved in seclusion incidents and 2,856 — 76% of whom were students with IEPs — were involved in restraint incidents. The data shows an average of 3.08 seclusions and 2.42 restraints per student involved.

Bucher also said that the use of seclusion and restraint is often a symptom of larger underlying problems including lack of teacher training or understaffing.

“While the raw numbers between two schools may look the same in terms of numbers of seclusion and restraint, the root causes are likely to vary widely between schools and districts and therefore require different approaches to address them,” Bucher said. “What schools need is support, technical assistance, coaching and resources to assist them that align to their local circumstances.”

Becker agrees that short staffing and teacher stress are contributing factors.

“They don’t have a staff member that can sit with my son in a room for an hour trying to help him calm down, and sometimes that’s what it takes,” Becker said.

Becker added that she doesn’t think staff realized how traumatizing the experiences have been for her son, who deals with claustrophobia and PTSD as a result of the seclusion and restraint.

Her son said he still has difficulties in school, but he believes the teachers in his current school have good intentions. When asked about how he could be better supported, he said better trained staff, who know how to talk to him and help calm him down, would be helpful.

Becker said her son hasn’t been restrained or secluded in about a year and a half. She said the school is a little more proactive now that he is older.

“It’s unfortunate because, now that he’s 14, we’re starting to try and do the work on self regulating and figuring out triggers… and we could have been doing this in kindergarten,” Becker said. “But when they’re little, it’s easier to just pick them up and put them in a room and now my son’s 5 feet 6 inches, 125 pounds so they can’t really do that to him anymore.”

Schools are not required under state law to take any action if they have a high number of seclusions and restraints, but Bucher said that schools are generally accepting of support DPI offers, including training around state law and requirements, behavioral intervention plans, trauma-informed practices and grant support to address behavioral needs.

The agency identified 32 outlier schools in the first year that data was reported to DPI. Bucher said 31 showed dramatic decreases in the use of seclusion and restraint in the following year — partly due to remote instruction during the COVID-19 pandemic.

One school that reported high numbers was Merrill Elementary, which is part of the Oshkosh Area School District. For the 2019-20 school year, Merrill reported 97 seclusion and 100 restraint incidents — a total of 197 incidents. The following year, the school reported 26 total incidents, and in the most recent year, its numbers rose to 47 total incidents.

Bucher said many of the schools with high numbers in the first year have showed sustained improvement.

Oshkosh Area School District is in its third year of a competitive grant offered by DPI to improve outcomes for students with IEPs. Through that grant, DPI has provided the district with improvement strategies and the district has worked with coaches who have provided additional support.

Linda Pierron, the district’s director of special education, said those programs help “teachers conquer those challenging behaviors and just focus on building those strong relationships with students.”

Spitzer-Resnick also said he would like to see DPI publicly praise school districts that have eliminated the use of seclusion and restraint.

“I’m confident that there are schools, school districts, school principals, who figured out how to never use seclusion and restraint,” Spitzer-Resnick said. “Those schools and school districts need to be amplified, need to be learned from and need to be used as examples for the other side of the story.”

Some of those suggestions would require additional resources for the department, Bucher said.

“From a capacity standpoint, the DPI could potentially gather anecdotal information about practices schools use that prevent the use of seclusion and restraint,” he said. “It would take far more time and resources to identify evidence-based practices… specific to the reduction of seclusion and restraint that could be scaled up, replicated and implemented at the state level.”

He noted DPI has sought additional funding to provide more support and resources for special education and mental health and will continue to do so.

Act 118, while it required DPI to collect seclusion and restraint data, did not provide any additional resources to address the issue.

The long-lasting impacts of seclusion and restraint

Advocates and parents of students who have experienced seclusion and restraint in classrooms emphasize that the consequences of the techniques on students last for a long time.

Fox Valley parent Stephanie Streck was a fourth-grade teacher at the school where her then-7-year-old son was restrained and secluded in 2020 and 2021. (She asked that the name of the school be withheld.) Her son’s experience, she said, changed her view on the issue.

“I had no idea that he would have an emotional response three years later to having a shoulder touched,” Streck said. The words staff used to describe the techniques, telling him they were keeping him ‘safe,’ as they did things that upset him, undermined his sense of trust and confused him, she added. “I had no idea that after only four times of people using nonviolent crisis intervention that he can’t hear the words ‘safe’ and ‘helpful’ and know them as the words that they really are.”

Streck’s son, who is autistic and has an individualized education program, did not learn certain rules until he had broken them, Streck said. Among those rules were playground boundaries that weren’t explained until he went too far, which led to teachers yelling at him, which led to him running and teachers running to catch him.

Streck said her son sometimes retreated to her classroom. She said she would allow him to stay until there was a break in her teaching and then she would encourage him to go back to his classroom.

“[My classroom] was kind of like his take-a-break space. That was tolerated for six months. There was no problem… One day, the principal decided that it was no longer acceptable for him to do so,” Streck said. She wasn’t told what prompted the change.

The next time he tried to go into his mother’s classroom the situation quickly escalated.

Streck said staff members, who were stopping him from going into the room, tried to prevent him from running and his reaction was to fight, swing his arms and throw his iPad. This led to two teachers using “nonviolent crisis intervention” techniques, which included pulling his wrist with one hand and his shoulder with the other hand. He was then placed in a room where a staff member held the door closed.

“He needed connection and he didn’t get any of that,” Streck said.

Streck said her son was restrained three times and secluded four times that year. Three years after the incidents, Streck said he still cannot be touched without flinching and has not returned full time to public school.

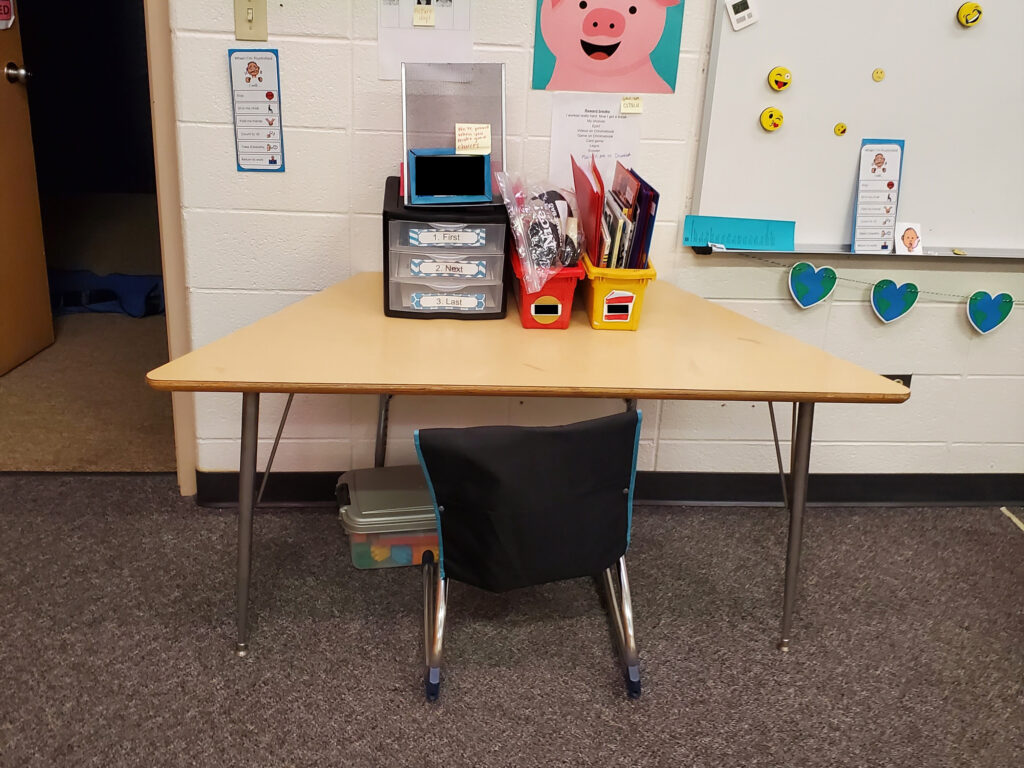

The workspace of Stephanie Streck’s son — next to a seclusion room at a Fox Valley school. Information containing her son’s name has been covered. (Photo courtesy Stephanie Streck)

Streck removed her son from the school in June 2021 and he now participates in a program that helps him visit a school building for about 35 minutes a week. She said he’s been trying to stay a little longer each week.

“I’m so grateful that my son doesn’t have any physical ailments from what happened but that also doesn’t discount the fact that he still has trauma,” Streck said. “Every decision you make has a cost and the decision to remove him from my math lesson in January of 2021 — we’re in such a negative balance because of it. … He has had so many missed opportunities for the last three years because of that experience.”

Streck has left the school and now works in a different district. She said it became too difficult for her to stay because she just viewed her colleagues differently.

“It’s a dang good school and I think that scares me the most. I liked working there. It’s a good place to be and they were still using seclusion and restraint in moments where it didn’t need to be used,” Streck said. “I can’t imagine schools that are understaffed or [where] the staff was uneducated.”

Lawmakers propose loosening restrictions on student restraint

Public school officials and advocates have criticized the current state budget for providing inadequate resources for special education in Wisconsin. Some say tight budgets are one reason the practices of seclusion and restraint continue in schools.

“If we could spend more money — money and more time and more resources — on helping kids expose what is going wrong and how they can ask for what they need, there would be less need for seclusion or restraint,” Streck said.

DPI Superintendent Jill Underly said in January that she was working on her next budget request to the state Legislature, including a special education reimbursement increase.

The most recent state budget raised that reimbursement rate from 30% to 33.3%; DPI and Gov. Tony Evers had requested that it be increased to 60%.

While declining to raise special education reimbursements to the two-thirds mark, some lawmakers also expressed concern that teachers aren’t able to use restraint in enough situations.

A bill introduced in October 2023, coauthored by Sen. Rachael Cabral-Guevara (R-Appleton) and Rep. Nate Gustafson (R-Neenah), would loosen current restrictions on use of restraint in classrooms, allowing its use in situations that present “clear, present, and imminent risk of serious emotional distress for the pupil or others or creates a considerable disruption to a classroom or other learning environment.”

The bill alarmed families and advocates.

Becker said seclusion and restraint is already not being used in accordance with state law. “If we loosen those parameters, I’m fearful of what would happen. I’m fearful someone would get — I mean, people already do get hurt, but I’m fearful it would be a lot more people getting hurt.”

Spitzer-Resnick said the bill would create a loophole in restrictions on seclusion and restraint large enough that someone could drive “a Mack truck” through it. Streck said the bill conflicts with the reality of how a classroom works.

Cabral-Guevara and Gustafson declined to be interviewed for this story and pointed the Wisconsin Examiner back to a co-sponsorship memo explaining their bill.

In the memo, lawmakers wrote that the safety of kids and teachers could “be muddied by the gray area of overcomplicated regulation.”

“When a classroom environment becomes unsafe, staff should be able to step in and de-escalate the situation so that students can get back to learning.”

Streck’s son’s classroom that the seclusion room was attached to. She noted it’s bareness and that it had no windows. (Photo courtesy Stephanie Streck)

The proposal would reverse the progress that’s been made on the issue, advocates say.

Disability Rights Wisconsin said in a statement that the proposal would increase the number of seclusions and restraints and would have a disproportionate impact on students with disabilities, with adverse, traumatic and even dangerous consequences.

The bill did not get a hearing this legislative session as lawmakers recently wrapped their work up for the year. However, advocates worry about the message it sends and whether it could come up again.

“Who’s gonna bring it forward next time and in a way that maybe it can get passed?” asked Mary Cerretti with Disability Rights Wisconsin. “It just worries me that it seems acceptable to people.”

Cerretti says she’s fearful because of her son’s experience.

Her 26-year-old son, Kyle, experienced repeated seclusions and restraints as a kindergartener before there were any state laws on the issue in Wisconsin. She said at the time when she was advocating for her son in school that she didn’t consider what the long-term consequences might be.

“It’s almost like that was the precedent that was set for him, which set the bar that everybody else is allowed to treat him badly because of a disability,” she said. “That’s where the source of his anger comes from.”

Cerretti said they’ve had to work with mental health professionals to find ways to support him through his difficulties. She said the knowledge that there are state laws in place and that she works to help other students has been helpful for him.

“As a parent and as a parent advocate, I firmly believe that it’s 100% on the actions of the staff and them not meeting the needs of the children,” Cerretti said. “I think we need to [work on] that first and we won’t see these practices being used as much.”

A father brings a lawsuit to fight his daughter’s treatment

Joshua Rabel became concerned about the treatment of his daughter at her school in south Wisconsin during the fall of 2018-19 school year. His family received notes about his daughter, who has Down syndrome and autism, with details of frequent incidents in which she was restrained and secluded. Notes from the school shared with the Examiner described the incidents, including instances of her hitting, kicking and throwing objects.Rabel said he didn’t understand why his daughter was getting so upset in school, but in many instances he felt staff members had taken actions that caused the disruptive behavior to escalate. For example, some situations described in the school notes included details about his daughter needing “physical assistance” with putting her head down.

“It was always the teachers saying, ‘Well, you’re not listening to me, head down’ — and they would force her head down onto a desk,” Rabel said. “That generally prompts a student who’s autistic to hit you. The teacher would then get all upset and be like, ‘Why are you hitting me?’”

Rabel said conversations with the school’s director of special education at the time and other school leadership were unproductive. Suggestions from him and his daughter’s IEP team, including the idea that they bring in a behavioral therapist to assist with his daughter, were disregarded.

The special education director at the time told him, “We’re the experts. We don’t need your help,” Rabel said.

Rabel, a Marine veteran, said he came to feel his daughter was being “attacked,” and turned it into an “operation” to get her appropriate support in school. Several DPI complaints were filed against the school about her treatment in the 2018-19 school year, and Rabel eventually filed a lawsuit against the school district in 2021.

The lawsuit alleged that staff members failed to provide adequate support for his daughter and forcibly restrained her while she was in the sixth grade at least 74 times on at least 32 separate school days between Oct. 17, 2018 and May 30, 2019, and that only 27 of those incidents were reported. It also noted the police were called on her several times that year.

She was kicked out of the school in 2019 and started attending alternative programs.

Rabel’s goal in the lawsuit was to get his daughter back into her local school with adequate support. The lawsuit was dismissed on the grounds that he had not exhausted other remedies available under federal law. But Rabel feels the lawsuit prompted the school to finally take action.

His daughter recently started back at the school full-time with behavioral therapists, and Rabel said she has “all the things that she needs to have a successful day.” Certain staff members involved in the seclusions and restraints no longer work with her and a new director of special education has been supportive.

“Had we simply gotten behavioral therapists and understood what to do and how to correct it, and to help [her] with intensive one-on-one therapy, it may not have happened,” Rabel said.

‘Districts should not torture children’: Seclusion and restraint in Wisconsin schools was originally published by the Wisconsin Examiner.

I think the title of this piece. “District should not torture children” is rather inflammatory and implies that these actions are happening in many school districts State wide. Having worked in public elementary schools for several decades, I have seen occasions where children can lose control and start attacking other students, teachers, and destroying the classroom. Responding often requires taking reasonable action to protect staff and students which sometimes may not exactly fit the protocol in the State law. All students have a right safe tp a safe and orderly class environment. Extreme examples cited should not be used to judge all of our State schools.