New Bay View Plan Envisions Redevelopment of 3 Key Sites

"We no longer have to be reactionary," says Alderwoman Marina Dimitrijevic.

A new Bay View land use plan attempts to chart a shared vision for the future of the neighborhood. It also includes conceptual plans for the redevelopment of three catalytic sites, but doesn’t include detailed plans for one that is likely to become a hot topic of discussion given the recently revealed planned closure of a large distribution facility.

“It’s the beginning of us writing the next chapters for ourselves and being the architects of our future,” said Alderwoman Marina Dimitrijevic in endorsing the plan, which includes everything from how to redevelop a vacant five-acre site to looking at where murals could be painted.

The proposal is an update to a broader 2008 effort, the Southeast Side Area Plan. Since then, the southside neighborhood has seen substantial rises in residential property values and investment in its commercial corridors. In 2020, Dimitrijevic called for the plan to be updated so the neighborhood could move from being “reactionary” to “visionary” when it came to increasing development pressure.

“This plan reflects a truly collaborative approach to placemaking. While we may not agree on every single aspect of it, we can be proud of it because all voices were heard and all positions were respected,” said Dimitrijevic when the City Plan Commission reviewed it on Sept. 24. “Some elements are visionary and forward-looking and envision changes, and some are intended to preserve certain unique aspects of our neighborhood that provide value and benefit our neighborhoods.”

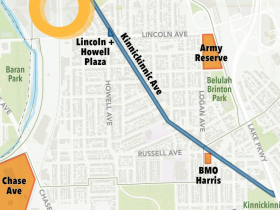

The plan includes conceptual design concepts for the redevelopment of the BMO Harris Bank site on the 2700 block of S. Kinnickinnic Ave. near E. Russell Ave., the UMOS-anchored former shopping center on S. Chase Avenue and the Army Reserve site at the eastern end of E. Lincoln Avenue. It also includes guidance on encouraging development along the mass transit corridors, sustaining the mix of uses on S. Howell Avenue, accommodating a wider array of housing options throughout the neighborhood and allowing industrial properties to be redeveloped for other uses.

“We had unprecedented levels of engagement,” said Department of City Development planner Monica Wauck Smith of the two-year process. She said 646 people attended the seven workshops and events, and even more people participated online.

Dimitrijevic said she was happy to see the proposal include sustainability components, a plan for improving the intersection of E. Lincoln Avenue, S. Howell Avenue and S. Kinnickinnic Avenue and “missing middle” housing like accessory dwelling units that are designed to fill an unserved gap between single-family homes and apartment buildings. She said residents made it clear they want more housing options, including more affordable options.

Josh Ehr, public spaces and development manager with the all-volunteer Bay View Neighborhood Association, said his organization is backing the proposal and its “balanced approach to development” and the suggested improvements to the streetscape of S. Kinnickinnic Avenue.

The Common Council unanimously adopted the plan on Oct. 31.

Army Reserve Site

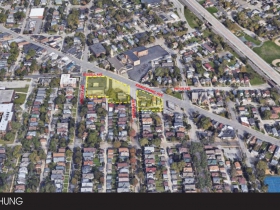

The 5.4-acre Army Reserve site, which functions as passive green space currently, presents the greatest immediate opportunity for development and greatest control because the city owns the property, 2372 S. Logan Ave. Prior Alderman Tony Zielinski was overruled by his colleagues in 2017 when he attempted to get the site designated as parkland, but DCD did not advance a compromise request for proposals (RFP) that would have left a portion of the site as public green space. The site sits just north of Beluah Brinton Park and includes a playground and several outdoor athletic fields and courts. The plans calls for E. Linus Street to be extended through the property and a 14-story tower at the northeast corner to afford lake views.

Wauck Smith said the city would look to issue a request for proposals for the development of the site, but cautioned that what’s built wouldn’t be a replica of the conceptual renderings. But she said the plan would guide the RFP, including pushing for lower-density development along S. Logan Avenue near existing homes, green space and higher-density development on the east side near Interstate 794. “We want to have a variety of different housing styles,” she said.

BMO Site

The BMO site became a hot-button issue in 2018 when F Street Group proposed a two-building apartment complex that would have included redeveloping the suburban-style bank property, a vacant commercial building last used by Bella’s Fat Cat restaurant, and nine adjacent properties. Contentious community meetings were held, but the proposal never advanced to a formal public hearing and was dropped.

Wauck Smith said the city sought to be proactive in including the site in its planning. The DCD design concept calls for the mass of any new buildings, up to five stories in height, to be pushed toward S. Kinnickinnic Ave. with townhomes or smaller structures near the homes at the rear of the site. The plan does not recommend conslidating the adjacent homes into the site, as was proposed in 2018. It does call for closing the one-block stretch of E. Russell Avenue between S. Kinnickinnic Avenue and S. Logan Avenue.

Chase Avenue

The Chase Avenue site is the largest and most conceptual of the three development concepts. A former shopping center, 2701 S. Chase Ave., is anchored today by social services agency UMOS and includes a Chuck E. Cheese restaurant. A Riv/Crete concrete plant is located at the rear of the site, along Interstate 94. DCD said community feedback called for a phased redevelopment approach and suggests a three-step approach that could start with outlot buildings on the large parking lot at S. Chase Ave. and W. Rosedale Ave., growing to commercial and industrial buildings at the rear of the site and an extension of the KK River Trail and ending with higher-density mixed-use development.

“Many of these recommendations are relevant to other sites along Chase Avenue,” said Wauck Smith of the many suburban-style buildings that dot the corridor.

What Happens With Stellantis Site?

A 43.5-acre industrial site is likely to find a new use. Stellantis, best known in the United States for its Chrysler, Dodge and Jeep brands, is working to close its distribution facility at 3280 S. Clement Ave. at the southern edge of the study area.

The draft plan discussed during the plan commission hearing did not include any explicit guidance on the site. But DCD, before the zoning committee hearing, did add a paragraph about the site to the final plan via a memo.

“The Chrysler Auto Part Distribution Center at 3280 S. Clement Avenue is a 43-acre site surrounded mostly by residential uses. Should this site become available in the future, redevelopment should re-use the existing buildings if possible, and focus on residential and other uses that are compatible with the residential context,” says a five-page memo.

The company included the plant’s closure in its bargaining agreement with the United Auto Workers (UAW). The approximately 100 jobs are to be transferred to a new “mega hub” in Belvidere, IL.

“At the beginning of the planning effort, indications were that Chrysler was committed to this location for the long-term,” said Wauck Smith in an email after this article was first published. “However, should Chrysler move forward with its plan to shutter the facility, we are confident that the current Plan is sufficient to guide future re-development in a way that is respectful of the residential context and allows flexibility at this privately-owned site. If the property is indeed sold to a developer, we look forward to working collaboratively on a development that meets the expectations in the Plan.”

The oldest part of the plant dates back to 1921 according to the Wisconsin Historical Society. It was originally a factory for Indiana-based Lafayette Motors. But the company was acquired by former GM president Charles Nash. Just a couple of years after starting production in Milwaukee, Nash consolidated Lafayette into his Kenosha-based Nash Motor Company and produced only Nash vehicles in Milwaukee. The plant, according to an industrial property survey by Mead & Hunt, had stopped manufacturing vehicles by 1937 and transitioned to a parts distribution facility.

The warehouse facilities on S. Clement Avenue are formed by a series of multi-story brick buildings connected by 1960s additions. It is largely surrounded by single-family homes or duplexes. It could also be adaptively reused: the Mead & Hunt report from 2016 says it is potentially eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places, which would make it eligible for historic preservation tax credits.

For more on the plant’s impending closure, see our Nov. 3 coverage.

Other Recommendations

The plan also calls for pedestrian-friendly improvements to S. Kinnickinnic Avenue, the neighborhood’s main street. A mix of curb extension, refuge islands, the narrowing or temporary or permanent closure of S. Allis Street and other interventions are proposed for possible use. “KK is an extremely long corridor, there is no need to treat it all the same,” said Wacuk Smith.

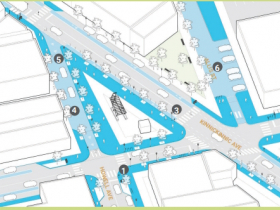

Design concepts are also included for narrowing S. Howell Avenue between E. Lincoln Avenue and S. Kinnickinnic Avenue and making it a bus-only street. The one-block stretch forms a triangular street intersection that creates long crossing distances for pedestrians and yields underutilized street space given that multiple routes guide vehicles to the same point.

Since 2000, only Downtown has seen higher growth in assessed value. Development has already occurred in the neighborhood, with a net increase of 585 new housing units since 2000, but included in that figure is more than 100 duplexes being converted to single-family homes. Approximately 66% of the housing was built before 1939 and only 5% since 1980. The average sale price in 2022 was $284,000.

Within the study area, approximately 60% of the land is occupied by single-family homes, 10% by parks and 9% by multi-family or mixed-use properties. Only 2% of the land is vacant, with much of that figure being driven by the Army Reserve site. The median household income is $66,837, more than $23,000 above the citywide figure, but more than 21% of Bay View households earn less than $35,000.

The planning process roughly followed the city-defined boundaries for the large, southside neighborhood. It ran from Becher Street and E. Bay Street on the north to Holt Avenue on the south, from Lake Michigan on the east to the Canadian Pacific railroad tracks and S. Chase Avenue on the west.

Cincinnati-based Yard & Company won a request-for-proposals process to design the plan. Milwaukee-based P3 Development Group worked on community outreach.

Development Concepts

Existing Site

UPDATE: An earlier version of this article said the Stellantis site was not explicitly mentioned. It was added on Oct. 16 via a memo.

Legislation Link - Urban Milwaukee members see direct links to legislation mentioned in this article. Join today

If you think stories like this are important, become a member of Urban Milwaukee and help support real, independent journalism. Plus you get some cool added benefits.

Political Contributions Tracker

Displaying political contributions between people mentioned in this story. Learn more.