Fewer High School Grads Choosing College

State’s 2-year campuses, technical colleges see big enrollment drops amid a hot labor market.

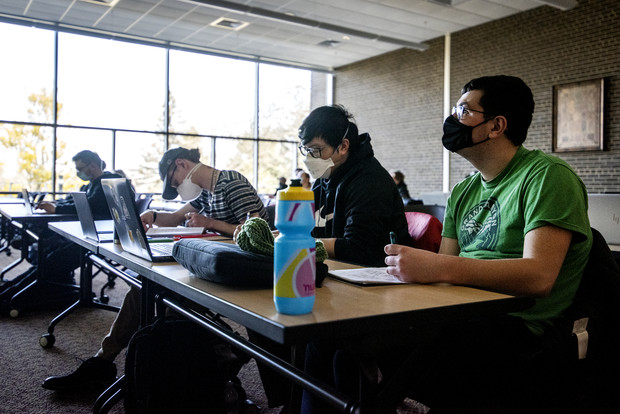

College students attend a class Friday, Feb. 18, 2022, at the UW-Green Bay campus in Sheboygan, Wis. Angela Major/WPR

Aside from the babble of Brush Creek and an occasional car pulling up to the small cluster of brick buildings capped with sloping metal roofs, the University of Wisconsin-Platteville Richland in rural Richland Center is mostly quiet on a February morning.

Inside the Wallace Student Center, freshmen Jackson Kinney and Heath Zumach study alone in the cafeteria. Kinney said he likes the small class sizes and saving money by going to college while living at home about 20 minutes away.

Kinney said his dad went to the same campus along with hundreds of others in the 1990s when it was known as UW-Richland County. But the campus feels a lot emptier these days.

Freshmen Jackson Kinney, left, and Heath Zumach study during a free period at UW-Platteville Richland’s Wallace Student Center cafeteria. They say they like saving money by pursuing associate degrees while living at home but worry about whether the campus will remain open with just 75 students enrolled as of fall 2021. Rich Kremer/WPR

“Will this campus be here in five years?” Kinney asked. “I’ve heard that question a lot, and we hope it is. But with enrollment this low, it makes you wonder how that is able to happen and how they’re able to support themselves.”

Zumach likes the small classes and personalized attention from professors. He and Kinney started their associate degree programs in September, but Zumach said he worries they won’t be able to finish there.

“I just pray that we get more students because the last thing you want is to end this year and find out, ‘Ope, nope, campus is closed. You have to go to Platteville,'” Zumach said.

As a whole, enrollment at the state’s 13 two-year branch campuses has fallen by nearly 57 percent, or around 7,400 students, since 2010. Some universities, like UW-River Falls, UW-Stevens Point and UW-Milwaukee, have seen enrollment decline between around 21 percent and 26 percent in that time, but the sharpest declines were at branch institutions

UW System chief data analyst Ben Passmore said it’s a huge challenge, in part because two-year campuses are access points for students who may not go to college otherwise.

“It seems pretty clear that the attractiveness of that kind of associate route, certainly to follow that all the way through the associate’s degree and transfer, declined over the last decade,” Passmore said. “I don’t have a great theory as to why.”

The percentage of Wisconsin high school students enrolling directly into college is also falling. The drop is most notable among young men, but the overall trend has big implications for individuals and institutions already facing significant, long-term enrollment declines.

After a recent peak of 70,717 high school graduates in 2008, the number fell 9.3 percent — or 6,584 individuals — by 2017 according to UW System data. There was another surge in 2018, but by that time a new trend was emerging.

College participation down, especially among young men

Passmore’s office analyzed data from the state Department of Public Instruction and found 59 percent of high school graduates in 2015 went directly into higher education. In 2019, that fell to 56 percent. That may not seem like a big difference, Passmore said, but a 3 percent drop among tens of thousands of students adds up.

“We saw these losses were not evenly distributed,” Passmore said. “In fact, more male students chose not to go on to school. That number dropped from 54 percent to about 50 percent.”

Historically, 32 percent of the state’s high school graduates have gone on to UW System schools, according to system data. That fell to 27.2 percent in the fall of 2020. The percentage of graduates going to two-year UW campuses fell to 2.6 percent that same year, after a recent peak of 5 percent in 2013. The data is not broken down by gender.

UW System data shows enrollment among men fell by 14.6 percent across all campuses between 2010 and 2021. That’s more than twice the 6.8 percent drop among women.

Over the past decade, the number of men enrolling at Wisconsin technical colleges fell by just more than 37.1 percent, according to the 2020-2021 Wisconsin Technical College System Fact Book. The drop was 32.4 percent among women.

At Sheboygan South High School, counselor Stephen Schneider said around half of graduates have typically gone on to college within a year of walking across the stage. He said more recently, that number has dropped to between 45 percent and 50 percent.

Schneider said regional employers are struggling to find enough employees, and they’re willing to bypass higher education, bring high school graduates in and train them internally.

“From a high school perspective, how do we respond to that in a way that best benefits our students?” Schneider asked. “Because that’s what we’re here for, right? To give our students as much advantage as we possibly can.”

Over the past decade, the district has been working with a nonprofit called Inspire Sheboygan County, which acts as a bridge between businesses and public schools. Sheboygan South offers work-based learning courses, called “co-ops,” sponsored by local businesses that pay students for part-time work as they explore career options.

Students attend a career fair Friday, Feb. 18, 2022, at Random Lake High School in Random Lake, Wis. Angela Major/WPR

Inspire Sheboygan County Executive Director Candice Boutelle said there’s a misconception that college is the only way for high school graduates to be successful, but the tide is changing. She said Inspire’s goal isn’t to dissuade anyone from choosing higher education. Instead, Boutelle said it’s about making sure those who aren’t planning for college have explored career options and made connections with employers.

This year, Inspire Sheboygan County expanded statewide with the launch of Inspire Wisconsin.

“It’s that normalizing and changing the messaging around, ‘Hey, you having a plan and having a full-time job is a really great thing to celebrate, the same way we’re going to celebrate kids who have their acceptance letter to their college,'” Boutelle said.

AJ Klug graduated from Plymouth High School in Sheboygan County last year. He said he felt lost as he neared graduation. Klug thought about going to college, but was deterred by the prospect of taking on lots of student debt.

Instead, he signed up for an 80-hour co-op program through his high school and local car dealership Van Horn Automotive. Klug said he felt at home working alongside master mechanics.

“I got into the shop and I said to myself, ‘This is actually something that I enjoy doing,’ you know? I found something. I don’t have to worry about it so much anymore,” he said.

Klug is taking classes to get a mechanic’s certification at Lakeshore Technical College. He’s taking advantage of the dealership’s apprenticeship program, which he said offers $6,500 in scholarships for tools and tuition. He expects to finish his certificate without any debt.

Survey results released by the Pew Research Center in November 2021 found financial concerns were a key reason for not pursuing a college degree. But 34 percent of men surveyed said they just didn’t want to go to college. Only one out of four women said the same.

Wayne Weber is UW-Platteville’s dean of the College of Business, Industry, Life Sciences and Agriculture and oversees programs at the university’s branch campuses in Richland Center and Baraboo. He said it appears some people, specifically young men, are missing the value of pursuing college degrees.

UW-Platteville Richland’s campus in Richland Center is mostly empty these days. Enrollment has fallen by 87 percent since a peak of 567 students in 2014. Last fall, there were 75 students enrolled. Rich Kremer/WPR

“We’re seeing not only that, but the achievement gap,” he said. “Women are achieving much more in higher education than men. So, how do we turn that around? I think part of it is changing the narrative and building leadership in men.”

A 2011 study by researchers at Georgetown University’s Center on Education and the Workforce found lifetime earnings rise steadily for those with various types of college degrees. For example, people with two-year associates degrees made around $423,000 more during a 40-year career than those with a high school diploma. Those with bachelor’s degrees made around $964,000 more than those with a diploma.

Doug Shapiro, executive director of the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center, said the implications go well beyond earnings.

“We’ve known for years that the jobs of the 21st century and the future require more, not less, in terms of education and technical skills of workers,” Shapiro said. “And it’s hard to see how we can continue to lead in that economy as a nation when fewer and fewer students are going to college.”

High school junior Dominic Montella, left, and his mother, Sherry, visit a career fair to explore employment options Friday, Feb. 18, 2022, at Random Lake High School in Random Lake, Wis. Angela Major/WPR

At the same time fewer Wisconsin high school graduates are choosing college, many businesses are raising wages and offering signing bonuses in an attempt to find workers. A Wisconsin Manufacturers & Commerce survey released in February found 88 percent of employers were struggling to hire.

Enrollments at two-year technical and community colleges follow economic conditions. When unemployment is high, like it was in the wake of the Great Recession, two-year enrollments tend to surge.

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit Wisconsin in 2020, unemployment spiked to 10.4 percent.

“And everybody had very high expectations, all this talk about how it’s going to be a windfall for us,” Wisconsin Technical College System President Morna Foy told WPR. “It’s going to be years of huge enrollment growth. And that didn’t happen.”

Instead, Foy said the annual decline of 2 or 3 percent the system had seen during the past decade accelerated to 19 percent over the last two years. She said most technical college students are working adults, many of whom have kids. Foy said the loss of child care, layoffs or reduced hours likely meant less bandwidth for college classes.

But Foy is optimistic that, through it all, demand for higher education, technical training and certifications will grow.

“I really believe that we are entering an era where people are constantly going to be upskilling and reskilling,” Foy said. “They’re going to need some help to do that. And we’re in the best position to do that.”

Students take notes during class Friday, Feb. 18, 2022, at the UW-Green Bay campus in Sheboygan, Wis. Angela Major/WPR

System officials have considered merging technical and two-year campuses

As the UW System grapples with enrollment declines at two-year campuses, leaders have discussed merging them with nearby technical colleges.

While every two-year UW System school has had substantial enrollment losses over the past decade, three have seen recent increases. Enrollments at UW-Green Bay campuses in Marinette, Manitowoc and Sheboygan have gone up between 8.7 percent and 18.8 percent amid the pandemic.

UW-Green Bay Chancellor Michael Alexander attributes that to the university’s Rising Phoenix initiative enabling high school students to earn two-year associates degrees before pursuing four-year bachelor’s degrees in those cities.

Alexander said UW-Green Bay is also purposely ceding ground to local technical colleges.

“We’re still going to offer associates degrees as part of what we do,” Alexander said. “But we’re not going to compete for a student who’s necessarily choosing between us and the technical college.”

Student Sarah Burmesch takes an exam on her computer in a common area Friday, Feb. 18, 2022, at the UW-Green Bay campus in Sheboygan, Wis. Angela Major/WPR

Sarah Burmesch is in her third year with UW-Green Bay and enrolled in a hybrid nursing program offering an associate of arts and sciences from the Sheboygan Campus in her hometown, an associate degree in nursing from Lakeshore Technical College and an online bachelor of science degree in nursing from Green Bay’s main campus.

“This was a really safe option just to come and take some classes while I was trying to figure out my life,” Burmesch said. “And also, I know this is talked about a lot, but it’s really helpful to have smaller class sizes rather than having big class sizes, so you can actually get to know your teachers and have more one-on-one help.”

With fewer state high school graduates choosing to go to college, a once reliable pool of enrollees from Wisconsin is drying up. It’s an added layer of uncertainty for colleges and universities facing declining enrollment and related budget challenges that will likely play out for years to come.

Listen to the WPR report here.

Editor’s note: Wisconsin Public Radio is a service of the University of Wisconsin-Madison and the Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.

Fewer Wisconsin high school students are going to college. A hot labor market may be the reason. was originally published by Wisconsin Public Radio.