Bipartisan Support For Teaching The Holocaust

As incidents of antisemitism rise in state, bipartisan bill mandates Holocaust education.

Recent national events are now part of history: The man storming the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6 wearing a “Camp Auschwitz” shirt. The chants of “Jews will not replace us” in Charlottesville, Virginia, in 2019. U.S. Congress member Marjorie Taylor Greene and her “Jewish space laser” theory.

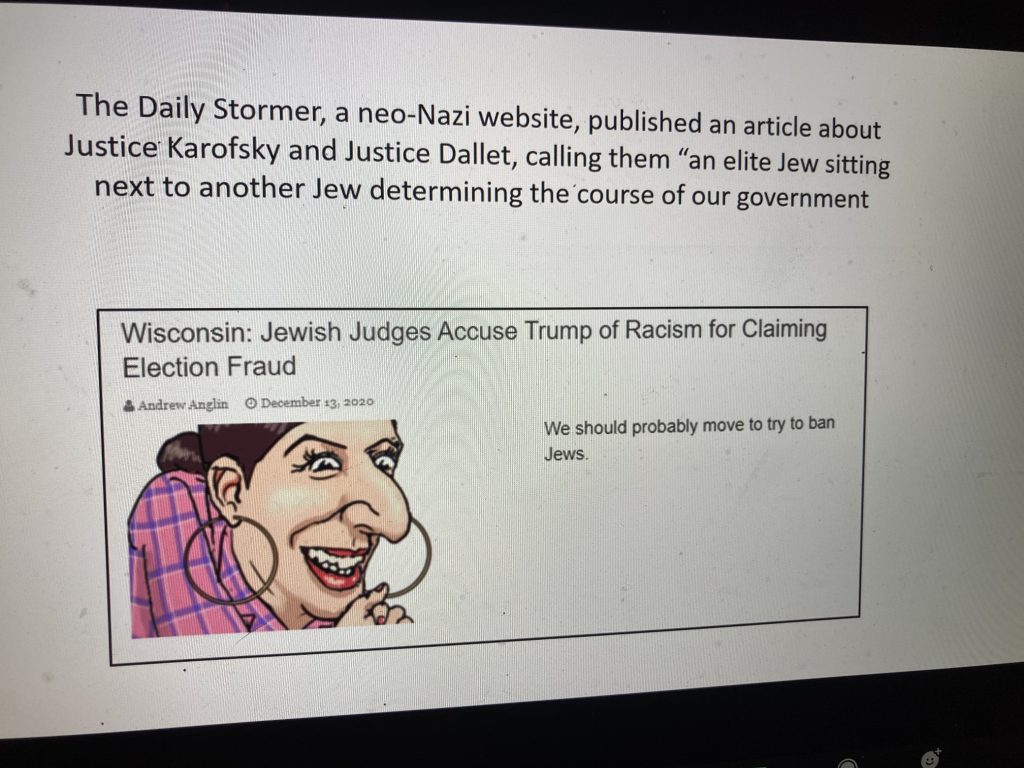

Closer to home, incidents of antisemitism are on the rise, including social media attacks on two Jewish members of the Wisconsin Supreme Court.

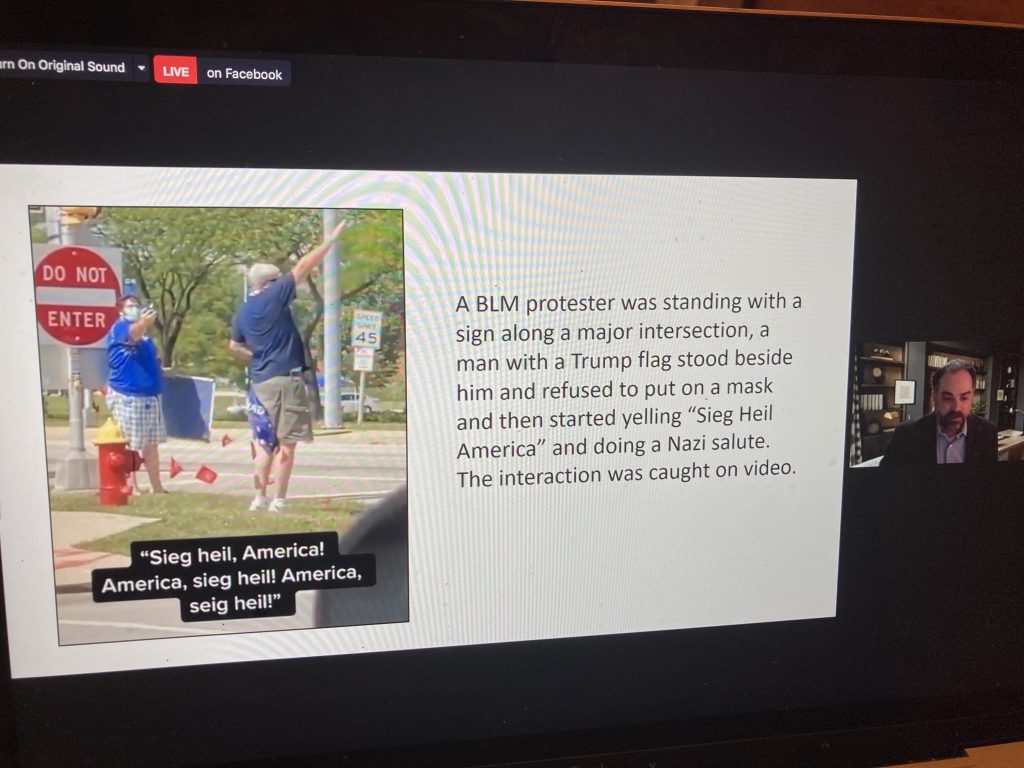

A counterprotester gives a Nazi salute at a Black Lives Matter event in Milwaukee. Screenshot from a March 3 presentation by Milwaukee Jewish Federation.

According to an annual audit released March 3 by the Jewish Community Relations Council (JCRC) and the Milwaukee Jewish Federation, Wisconsinites experienced 99 incidents of antisemitism in 2020, a 36% increase from the year before; the group says these are reports that are verified and corroborated.

“We are seeing a significant increase in overt antisemitic expression laden with conspiracy theories and hate group rhetoric,” said Brian Schupper, chair of the JCRC in a statement. “The audit helps us discuss these worrisome trends with our community partners and understand where we need to focus our efforts.”

Antisemitic comments directed at Jewish members of the Wisconsin Supreme Court. Screenshot from March 3 presentation.

Several of the troubling incidents involved Nazi imagery, including reports of people doing the Nazi sieg heil salute at a Republican Party of Milwaukee County “Protect the Vote Rally” on Nov. 7, and a posting on Aug. 26 from a Kenosha middle school teacher posing in front of a swastika, writing, “Glad they finally got rid of 2 terrorists in Kenosha [referring to Kyle Rittenhouse’s victims]. Now get rid of the rest.”

It appears most Wisconsin legislators, regardless of party affiliation, believe one way to counter the spread of hate is through education. On Friday, the Senate Committee on Education passed a bill that would mandate Holocaust education by inserting it into the state’s social studies standards, requiring instruction on “the Holocaust and other genocides” in grades 5 through 12.

According to a national survey released by Claims Conference, 58% of people surveyed believed something like the Holocaust could happen again. Forty-nine percent of millennials surveyed could not name one of the 40,000 ghettos or camps where Jews were slaughtered. And 22% of those did not know about the Holocaust at all.

“I can remember interviewing Holocaust survivors when I was a teenager as part of a

youth group project to preserve their stories. While they shared survival stories that were nothing short of heroic, their stories were also those of tragic loss,” Rep. Lisa Subeck (D-Madison), one of the bill’s authors and one of Wisconsin’s three Jewish legislators, said in a statement. “Unfortunately, today’s children will likely never meet a Holocaust survivor. While they will not have a chance, as I did, to listen to their firsthand stories, it is incumbent upon us to make sure this history is never repeated.”

An eye-opening experience

Sen. Alberta Darling (R-River Hills ), another author of the bill, became a champion of Holocaust education after a visit to Auschwitz in Germany. At the Feb. 23 meeting of the Senate Education Committee that she chairs, Darling and several other co-sponsors spoke with passion about the need for such a measure. She said this history helps us learn and become “sensitive to man’s inhumanity to man, and to learn from that experience, so that experience of inhumanity isn’t repeated again.”

Darling and the other members of a delegation saw a film before their tour of the camp. “The film was about people getting on the train, who are going to go to concentration camps,” Darling said. “It hurt the heart so much to see families going on this train, knowing what was going to happen to them. And I was very struck by one particular image of a mom holding the hand of her child …. and then you’d see these shoes of children who had been exterminated. And seeing these little shoes really, really bothered me. So this just moved me to the point that I thought if I ever have the opportunity, I’m going to work on making sure that people understand what happened there.”

Nancy Kennedy Barnett, spoke at the hearing as a representative of the Nathan and Esther Pelz Holocaust Education Resource Center (HERC). The center has a speakers’ bureau that presents educational programs around the state. If the bill passes, it will provide support and curriculum to educators.

“I am the child of a Holocaust survivor from Budapest Hungary, and I’m a second generation speaker teaching my father’s story of survival,” Barnett said. “We have lost witnesses to this horrific time in history, but the lessons and messages cannot be forgotten. When I teach, I don’t only speak about the atrocities of the past; I use it as a lens to illustrate what can happen when hatred and bullying is left unchecked.”

Barnett recalled an incident that happened in one of classrooms where she taught in Hartland, Wis., after a group of 8th graders had visited the Illinois Holocaust Museum in Skokie, Ill. “After I had spent about an hour with them telling my father’s story, an eighth grade girl raised her hand and, clearly troubled, said to me, ‘I was talking to my mom last night, and my mom says that she has a friend that said the Holocaust never happened.’”

Barnett said students need help separating fact from fiction, and can apply lessons from Holocaust studies to other incidences of hate and discrimination. “Students must understand the consequences of hate. They must not be bystanders,” she continued. “They can be an upstander instead, by being someone who gets involved. They can be proactive and have the courage to speak up and care, but they must know the truth. Holocaust education teaches an understanding of the ramifications of prejudice, racism and stereotyping, and an examination of what it means to be a responsible and respectful person.”

Many members of the committee appeared moved by the virtual testimonial of Eva Zaret, a Holocaust survivor from Budapest, Hungary, who came to the U.S. when she was 20. Zaret, who is Jewish, lost most of her family in the camps, and has devoted her later years to teaching about the Holocaust in middle schools, high schools and colleges.

“I get such a response from the children,” said Zaret. “They are waiting to hug me and sometimes that takes an hour and a half after I speak, and they cry and they want to learn. I feel that this is the most important thing we can do as human beings is teach our children.”

Holding up a photograph of her parents, she talked about attending first grade at age 6. “After my father was taken, my friends didn’t want to speak to us. All of a sudden, I realized that we were different than my friends. They told me I killed Christ and cannot talk to me,” she recalled.

Zaret said she will never forget the hate, violence and horrors she witnessed. “I escaped from Vienna to come to the United States,” she continued. “And this is my beloved country. I want people to learn about the Holocaust and atrocities, because it’s not just the 6 million Jews who were killed. How about the other millions of people who stood by or did nothing or hated us just for being Jewish? I will do anything possible to help while I’m alive.”

Unprecedented bipartisan support

Mark Miller, chair of the board at HERC, tells Wisconsin Examiner he is extremely encouraged by the bipartisan support for the the Holocaust Education Bill, which passed the Assembly in early 2020 before COVID-19 derailed everything, including pending legislation. He says the universal support for the measure speaks volumes.

Miller says the generation of Holocaust survivors is dying, so it is up to the next generation to carry on the knowledge. “It was one of the most horrible events ever in the history of mankind,” he says. “And it will translate to other injustices also; it gives young people a perspective that they need to have to be better citizens.”

The Holocaust Education Resource Center is setting up a website and will make curriculum available for free, says Miller. “Teachers have a lot on their plate. But our commitment here is to provide a resource that everyone can go to, to pull lesson plans, to teach their young people about this,” he continues. “If you don’t want this to happen again, and you see the way society is fraying, and split up, then you have to educate young people because they’re the future.”

Miller got involved in HERC because his wife’s family survived the Holocaust and he has learned from their stories. “If you’re a survivor, you live it every day, you talk about it every day,” he says. “It’s how you survive. The weight of the atrocities — very few human beings mentally can handle that. And the way you handle that is by talking about it by sharing, by interacting with other people.

“This story needs to be told because that’s how they win,” says Miller. “These people didn’t die in vain. They are going to become the educators. And that I know up in heaven, that they’re going to have a little smile that they won — that Hitler didn’t win.”

‘No hidden agenda’

Jonathan Pollack, an instructor in the history department of Madison College and an honorary scholar in UW-Madison’s Center for Jewish Studies, tells Wisconsin Examiner he finds the Holocaust Education bill “really kind of refreshing.” Despite the level of party-based rancor in Wisconsin, he calls it “a bipartisan slam-dunk bill, and I feel like we don’t see many of those.”

Because of the range of opinions in the Jewish community and beyond on the actions of Israel, he was glad to see that the bill avoided the trap of labeling criticism of the Israeli military and the government of Benjamin Netanyahu as antisemitism. “It was pretty straightforward,” he says of the bill. “And there was no weird, hidden agenda in there.”

Pollack says incidents like the Baraboo high schoolers photographed in 2018 doing a Nazi salute showed the importance of education. “In the aftermath of that, people were saying there ought to be something in Wisconsin that mandates Holocaust education, because they just don’t know.”

Most of Pollack’s classes cover modern U.S. history, including African American and Native American history. “In each of these, the subject of genocide comes up, in Native American history, first and foremost,” he says. “But I certainly avoid Holocaust comparisons. I really like to talk about the differences.”

Pollack said most of his college students have possessed at least a “basic knowledge” of the Holocaust and he hasn’t experienced Holocaust denial or students believing the Jews caused the Holocaust, another disturbing finding from the Claims Conference study.

However, says Pollack, progress toward racial equity in this country is slow, despite ethnic studies requirements that became part of college curriculums in the 1980s.

State-mandated standards are certainly a step in the right direction, but not enough to make lasting change. “There’s still racism, still institutional racism, and all the ethnic studies in the world isn’t going to help especially students of color who don’t have the money to pay full tuition,” says Pollack. “Does this make a difference? Will there be no more Baraboo because there’s this line in the state statutes that governs what goes on in Wisconsin schools, that there has to be X amount of time spent on the Holocaust? I doubt it.”

If the bill sails through, as expected, it will be interesting to follow the progress of Holocaust education in Wisconsin, says Pollack. His hope is that the Holocaust will be taught as part of a historical context, including important stories of resistance. “At the university level people studying the Holocaust began looking at at genocide and looking at the the atrocities and the victims and so forth, and that where recent scholarship has gotten more into the Warsaw ghetto and the various partisan movements around Europe,” he says.

Too much focus on atrocities can leave students feeling despair, he adds. “Even with Jewish students who came up through Jewish day schools in Chicago and in New York and elsewhere, our modern Jewish history education is just focused on the Holocaust,” says Pollack. “It was just like looking in a bottomless pit. There’s more to Jewish history than that. There’s more to even the Holocaust than that.”

He credits his mentor David Sorkin, a former UW-Madison professor now at Yale, for his ideas on how to teach the Holocaust. “He said to teach a class entirely on the Holocaust is to rob it of its context; to carefully understand the Holocaust, you have to look at it in the context of the Jewish experience in Germany and the rest of Europe.”

Making connections

Kiel Majewski, the co-founder of a grassroots truth and reconciliation organization called Together We Remember, was the first executive director of CANDLES Holocaust Museum and Education Center in Terre Haute, Indiana. He shared an office with Auschwitz survivor Eva Kor, who was subject to medical experiments in the camp. An arsonist destroyed the museum in 2003.

“We need this education, and it would be most useful if it leads us to address the history of genocide and atrocity in the land now known as the U.S.” Majewski says, again citing the Claims Conference study on how many millennials can’t name a concentration camp. “Compare that to a survey released the same year by Southern Poverty Law Center which found that only 9% of high school seniors in the U.S. — 9%! — could name slavery as a primary cause of the Civil War. Is it any wonder that in the mainstream we have trouble recognizing structural racism and its longstanding effects?”

Majewski believes the Legislature’s attempt to bring these stories into classrooms will strengthen the education of young people. “The Holocaust is unique, and all genocides are unique in their own right,” he says. “Looking closer at them reveals both parallels and pitfalls in connecting the dots from past to present and across cultures. We can and should educate students to understand the nuances while appreciating how these moments in history are connected and part of the bigger challenge of bending the arc toward justice for the planet and all of its people.”

Reprinted with permission of Wisconsin Examiner.

If you think stories like this are important, become a member of Urban Milwaukee and help support real, independent journalism. Plus you get some cool added benefits.