Meet the COVID-19 Naysayers

They downplay danger, oppose masks and resist a vaccine.

Protesters are seen at a rally at the Wisconsin State Capitol on April 24, 2020. They were demanding an end to the wide-ranging shutdown of normal life and business in Wisconsin aimed at curbing the coronavirus pandemic. Weeks later, Gov. Tony Evers’ Safer at Home order was overturned by the Wisconsin Supreme Court. Even as the state’s pandemic death toll surges, some Wisconsin residents believe the threat of COVID-19 is overblown, that masks are dangerous and restrictions to curb the disease are part of a plot to ruin the economy and make people dependent on the government. Will Cioci / Wisconsin Watch

Dan trusts practically nothing the media and medical establishments say about the COVID-19 pandemic. He considers the threat overblown. And saying as much on Twitter has triggered some heated arguments.

“You question anything, you get told you’re going to kill grandma or you’re doing something wrong, and you’re made to feel like you’re unpatriotic for not putting on a mask,” he told Wisconsin Watch.

Dan of Muskego, Wisconsin, is an active voter who’s worked for the past several years at a restaurant. He requested that Wisconsin Watch omit his last name for fear of online harassment. He counts himself as one of the few people watching the “real world,” unlike those who “live in ignorance.”

Believing that “both sides of the aisle are completely corrupt,” Dan characterizes COVID-19 stay-at-home measures as a deliberate attempt by Democratic politicians to “tank” the U.S. economy.

He’s not alone in seeing stay-at-home orders and business restrictions as a coordinated assault on commerce rather than a last-resort measure to slow the spread of a highly infectious disease that has claimed more than a quarter of a million lives in the United States, including more than 3,700 in Wisconsin.

Coronavirus skeptics have made themselves known in Wisconsin throughout the pandemic. In the spring, an estimated 1,500 protesters gathered at the Wisconsin State Capitol, demanding that the statewide COVID-19 lockdown be lifted. Others blame the wearing of masks — a key public health strategy — for causing rather than preventing infection.

Over the summer, members of the Appleton City Council were forced to bat down unfounded rumors that contact tracers were surveilling residents, a narrative that picked up traction on the Facebook page Wisconsinites Against Excessive Quarantine. And in an extreme example, staffers at the Milwaukee Health Department recently received death threats for enforcing COVID-19 orders, according to the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel.

Misinformation has been a destructive force working against the state’s coronavirus response, said Dr. Jeff Pothof, chief quality and safety officer with UW Health.

“I don’t think any of us thought, when the pandemic started, that one of the biggest barriers we’d have to overcome would be misinformation from people who have no idea what they’re talking about getting a message out there that leads people to make decisions that are not in their best interest,” he said.

Skeptics interviewed by Wisconsin Watch include people who embrace the increasingly popular QAnon conspiracy theory, are generally suspicious of vaccinations, consume nontraditional medical advice and value personal freedom above what they believe are exaggerated public health considerations. They also acknowledge that their beliefs have put them crossways at work and with family.

Conspiratorial thinking is common during national crises, said Dietram Scheufele, a communications professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison who studies public attitudes and policy dynamics surrounding emerging science.

“It’s partly human nature,” Scheufele said. “We’ve seen this again and again.”

Evolving science feeds conspiracies

University of Wisconsin-Madison professor Dietram Scheufele says conspiratorial thinking is common during national crises, such as the COVID-19 pandemic. “We take new information and make it fit what we already believe,” he says. Life Sciences Communication / University of Wisconsin-Madison

What makes COVID-19 pandemic conspiracy theories different from those related to the assassination of President John F. Kennedy or the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks are the implications for public health and welfare.

And unlike those earlier seismic events, “We didn’t have a U.S. government and a president who fed some of those conspiracy theories, who questioned our system of disseminating correct information,” Scheufele said.

Another factor is that spreading COVID-19 disinformation can be lucrative.

“Even 20 years ago, we didn’t have an information system … where the fiscal incentive, the monetary incentive, is to promote ideas like this,” said Scheufele, adding that “outrageous” content produces larger audiences “which means data — which means profit.”

Scientists have been tasked with striking down misinformation on COVID-19 while their own understanding of the new coronavirus evolves in real time — leading to confusion, skepticism and even denial around the respiratory disease.

“We knew, going into February, March — maybe earlier — we knew that we would produce a lot of science that would turn out to be wrong, … a lot of studies that eventually wouldn’t work out in terms of therapies and vaccines and everything else,” he said. “The vast majority of Americans who never pay attention to science paid attention in the past five months. You make a mistake in the spotlight with 330 million Americans watching, that mistake — maybe a small one — will be seen by everybody.”

The roots of denialism

That so many people believe the pandemic isn’t real, or at least isn’t a big deal — despite grim scenes playing out in hospitals and increasingly desperate pleas from public health officials to stay home for the holidays — is partly the work of mind mechanisms known as biased assimilation and motivated reasoning.

“We take new information and make it fit what we already believe,” Scheufele said. “It doesn’t really matter what you tell me because I’m just going to fit it into my existing belief system and I’m really not going to change what I think.

“Of course, during a time like a pandemic — where we do need to change behaviors, we do need to change our interactions with one another and our daily routines — that’s just utterly dysfunctional.”

Having worked in education for 28 years, “Susan” said she would walk away from her job at a school district in northern Wisconsin if she is required to be vaccinated against the coronavirus. She questions how safe or effective the vaccines would be, given that they were developed in record-breaking time. Susan asked Wisconsin Watch to use a pseudonym because she fears coming out against vaccination could jeopardize her career.

“No, I would never, ever take it,” she said. “If someone tells me because I work in the school system, ‘You have to get this,’ I’ll quit my job. … A lot of people in our school district and in the health care field up here feel the same exact way; they do not want it. It was done way too fast.”

Roughly three in five U.S. adults said they “would definitely or probably” get a COVID-19 vaccine in a national survey conducted by Pew Research Center in November — up from about half of respondents in September.

A health care worker in a PAPR hood walks through the hallway inside a COVID-19 unit at UW Health’s University Hospital in Madison, Wis., on Nov. 17, 2020. The pandemic has hit Wisconsin and other Midwestern states hard in recent months, causing record levels of infections and death. Angela Major / WPR

“As vaccines for the coronavirus enter review for emergency use by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, the share of Americans who say they plan to get vaccinated has increased as the public has grown more confident that the development process will deliver a safe and effective vaccine,” the researchers noted.

Susan believes the pandemic is real but overhyped. She tested positive for COVID-19 on Sept. 29, after falling ill with similar symptoms in January. (She believes she caught the coronavirus twice.)

In both cases, Susan experienced severe burning in her lungs, fever, muscle aches, shivers and chills and a cough, which was most severe the first time around. After missing nearly a month of work between the two bouts of illness, she’s still short of breath and has difficulty walking down the hallway at work.

Mixed mask messages breed distrust

Susan blames the mask she is required to wear on the job for her labored breathing and generally disapproves of Gov. Tony Evers’ mask mandate. She doesn’t think masks help slow the spread of COVID-19, insisting that they instead represent a health hazard.

“I’m not in favor of masks,” she said. “I think that since the mask mandate went into effect, it got worse in northern Wisconsin.”

The CDC reversed course on April 3, which caused some to question the agency’s advice. Subsequent studies have verified that masks protect both wearers and others from the spray of respiratory droplets of virus when worn over the nose and mouth. The CDC recently recommended “universal mask wearing” for all indoor activity outside an individual’s home and for outdoor activities where six feet of social distancing cannot be maintained.

Pressed on why she believes the mask mandate helped spread the virus in her area, Susan responded, “Because the particles are still getting in there and we’re creating more bacteria in our immune system. We’re not letting ourselves have an immune system; it’s depleting our immune systems, is what it’s doing.”

“This is a little community up here,” she elaborated. “Price County and Ashland County, we were so free without COVID for forever, until after I think it was Memorial Day and everything broke loose. We had a lot of people coming up from the cities. … After that, and as soon as that mask mandate went into effect, it seems like it just went crazy. When we went back to school, it was like, whoa — then it really went crazy.”

Protesters gather at a rally at the Wisconsin State Capitol on April 24, 2020. They were demanding an end to the wide-ranging shutdown of normal life and business in Wisconsin aimed at curbing the coronavirus pandemic. Gov. Tony Evers’ Safer at Home order was later overturned by the Wisconsin Supreme Court. Will Cioci / Wisconsin Watch

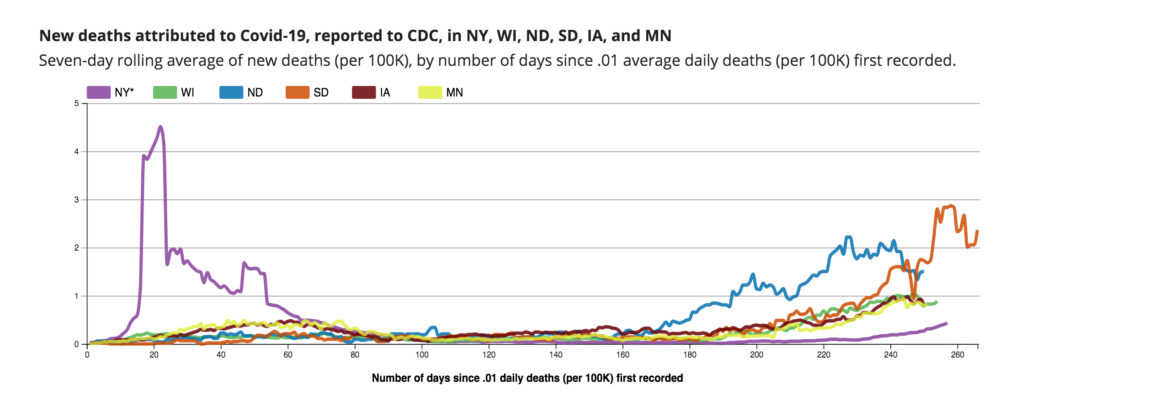

What happened in northern Wisconsin was not unique, however. The Upper Midwest, which was spared the surge that hit New York in April and early May, began seeing an increase in COVID-19 infections this summer that has continued into the winter in states with a variety of mandates around masking.

Describing herself as a careful news and social media consumer who doesn’t believe everything she sees and hears, Susan believes the mainstream media has been corrupted by profit motives, just like drugmakers that produce vaccines.

Although she’s fiercely opposed to wearing masks and taking a COVID-19 vaccine, Susan favors another statewide stay-at-home order to combat the virus that has taken her breath away. And she trusts public health officials such as Dr. Anthony Fauci — sometimes.

“Do I believe Dr. Fauci? Damn right I believe him. He’s damn good at what he does and I am a firm believer in him,” she said, pausing. “Except for the mask part of it. I don’t believe that.”

‘I do not need to be afraid’

Theresa Zanon, of Mukwonago, Wis., is seen at a protest of Gov. Tony Evers’ Safer at Home order at the Wisconsin State Capitol on April 24, 2020. Zanon owns a bar and grill that was shuttered under the order to curb the spread of COVID-19; the Wisconsin Supreme Court overturned the order weeks later. At the time, Zanon accused the government of misrepresenting the number of people who have tested positive for the virus, citing research she did on the internet. Brad Horn / Wisconsin Watch

Julie Drigot believes that “wearing a mask is absolutely insane,” and detests the phrase “the new normal” when describing how the COVID-19 pandemic has changed many aspects of everyday living.

“No, I’m sorry, keeping people locked up is not ever going to be normal, and wearing diapers across my mouth is never going to be normal,” she said. “I have a lot of issues with dizziness, especially while I’m riding or driving in the car … why would I possibly do anything to restrict my airflow?”

Drigot lives alone in the rural hamlet of Little Prairie, nestled about halfway between Beloit and Milwaukee. A longtime elementary school teacher in Milwaukee, she spent most of her career in Waldorf education. She recently moved to the countryside to fulfill her lifelong dream of running a small farm school; a handful of children visit her a couple of times a week for instruction.

She was “paralyzed with fear” during the early days of the pandemic, Drigot said. As someone with a pre-existing medical condition, she felt she was at risk of falling severely ill with COVID-19.

“‘I can’t afford to get this; this is going to kill me,’” she recalled thinking. “Then I was like everybody else. I was as cautious as cautious could be. I was wiping off my mail and groceries, and really terrified.”

Alarmed by the warnings from the news media and public health officials, Drigot went looking for information sources that were more reassuring.

“I started to realize, ‘Wait a minute. I’m OK. I’m gonna be OK. I’m a human being, I’m a spark of light having this little moment on earth, and I do not need to be afraid of a virus,’ ” she said. “This is ridiculous.”

The Upper Midwest, which was spared the surge that hit New York in April and early May, began seeing an increase in COVID-19 infections this summer that escalated in the fall and winter. U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Asked to provide her sources, she pointed Wisconsin Watch to a number of websites that have been known to produce pseudoscientific content, such as The HighWire with Del Bigtree, a major voice in the national anti-vaccination movement.

The website has promoted anti-mask sentiment and the debunked “Great Reset” conspiracy theory, which claims world leaders orchestrated the pandemic to destroy capitalism and take control of the global economy.

In July, Bigtree’s YouTube account was deactivated for pushing misinformation about vaccines and COVID-19, including his suggestion that people should intentionally expose themselves to the coronavirus. And Facebook just announced it plans to remove misinformation about COVID-19 vaccinations from that platform and Instagram.

Anti-vax sentiment crosses parties

A lifelong “liberal Democrat,” Drigot said she’s been skeptical of vaccines for years, echoing the unfounded concern that these inoculations can damage the brain and nervous system.

“I’ve been a teacher in the schools for a long, long time,” she said. “Over 35, 45 years, I’ve seen a huge increase in neurological problems in children. Do I know the answer? Do I suspect it could be vaccines? Well, I might.”

Pothof worries that vaccine hesitancy could be another major obstacle in Wisconsin’s effort to combat the pandemic.

“We’re so polarized right now, what we don’t want to see is a large proportion of the population to not get the vaccine because … they don’t want to believe this (pandemic) is true,” he said.

About two out of five Americans say they would likely opt out of a COVID-19 vaccine, according to Pew.

Phlebotomist Essaha Ceesay works in a COVID-19 unit on Nov. 17, 2020, at UW Health’s University Hospital in Madison, Wis. Angela Major / WPR

Scheufele said anti-vaccination sentiment is not a left-right issue, and it has led to a recent resurgence of diseases including measles.

“We’ve seen really low vaccination rates in the child care facilities of Cisco Systems, Facebook, Google, so, highly educated parents in Silicon Valley that didn’t want to vaccinate their children for the same reasons that they buy things at Whole Foods, because they have some understanding of ‘natural’ that doesn’t align with the scientific consensus.”

More than anything, Drigot takes issue with the “censorship” of voices like Bigtree’s. All viewpoints should be shared freely, she said.

“I’m not trying to say I know different or better than you or anyone else, I just know there are alternative thoughts about it that are serious,” she said. “People need to be aware of it, and they need to be able to read it. We’re not children, after all. We’re not babies. We’re thinking human beings and we need to have information. … I can make up my own mind, thank you very much, right? That’s my attitude.”

‘Looking for the truth’

Describing himself as a politically “middle of the road,” Dan admits to having a history of conspiratorial thinking. But he takes issue with the term “conspiracy theory,” which he says has been used to discredit truth-seekers. He cites the book “Rule by Secrecy” by Jim Marrs, a prominent figure in the JFK assassination and Sept. 11 conspiracy theory movements, as an early influence.

“Looking for the truth, you kind of guide yourself there, and eventually you come to your own understanding of what’s going on,” he said.

“As much as the media attacks it,” he said, “it makes it more legit to me.”

He scoffs at the notion of taking one of the yet-to-be-approved coronavirus vaccines. He’s wary of how quickly the vaccines were developed and wonders whether the “end game” is forced vaccinations. Public health institutions like the CDC are as suspicious as everything else to him — pharmaceutical companies, politicians, CNN. In his eyes, all evidence is refutable.

“There’s no real information. You can’t necessarily trust the CDC because you can go somewhere else and find conflicting information,” he said. “I mean, anybody that does any sort of research can find a conflicting point on anything that anybody says. That makes it really difficult to try to make an argument.”

Arguing has caused difficulty in his personal life, however. He used to talk freely about politics with his mother, but that changed during Trump’s presidency, he said.

“We’re being pitted against each other and it doesn’t feel very good,” Dan said. “And if you say anything, you’re going to cause a conflict. I’m in a personal situation with my mother; I mean, it’s just awful. It’s terrible. It’s not fun to be living in this.”

Howard Hardee is a Madison-based journalist who created a misinformation toolkit for consumers funded by the Craig Newmark Philanthropies. He is a fellow at First Draft, an organization that trains journalists to detect and report on disinformation. Wisconsin Watch (wisconsinwatch.org) collaborates with Wisconsin Public Radio, PBS Wisconsin, other news media and the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by Wisconsin Watch do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.

-

Wisconsin Lacks Clear System for Tracking Police Caught Lying

May 9th, 2024 by Jacob Resneck

May 9th, 2024 by Jacob Resneck

-

Voters With Disabilities Demand Electronic Voting Option

Apr 18th, 2024 by Alexander Shur

Apr 18th, 2024 by Alexander Shur

-

Few SNAP Recipients Reimbursed for Spoiled Food

Apr 9th, 2024 by Addie Costello

Apr 9th, 2024 by Addie Costello