Metro Pay Gap for Women Improves

Study finds Milwaukee County women earn 85% of what men get compared to 79% nationally, 76% in Waukesha County.

Pay is catching up for women in Wisconsin, but they aren’t yet even with men. And just letting the trend continue on its own might not be enough to eliminate the difference.

Those are the findings of a new report that the Wisconsin Policy Forum (WPF) issued earlier this month. The report was commissioned by the Women’s Leadership Coalition, made up of three professional women’s organizations: TEMPO Milwaukee, Professional Dimensions and Milwaukee Women Inc.

The brief report, published online, finds that while women’s earnings might be getting closer to what men earn, there’s still a double-digit difference. It focuses on Milwaukee County, but includes adjacent Waukesha County for comparison, along with some national data.

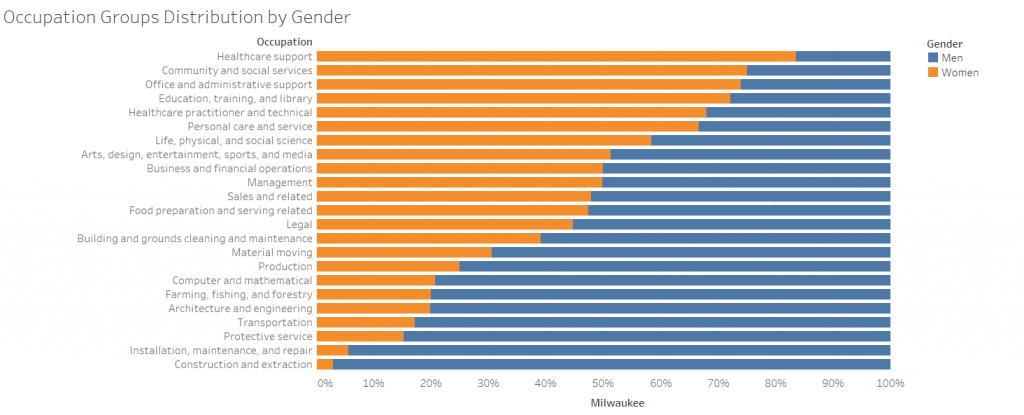

This chart hows the distribution by gender of jobs in various occupation groups in Milwaukee. Occupational distribution is a factor in the earnings gap between men and women, research shows. Chart provided by Wisconsin Policy Forum.

Using figures from the U.S. Census bureau for annual earnings of full-time workers, WPF researchers Joe Peterangelo and Betsy Mueller found that in 2018, median annual earnings of women in Milwaukee County were 85% that of men — $41,206, compared with $48,413.

In Waukesha County, the gap was wider than in Milwaukee County, with median annual earnings for women 76% of what men earned. The same was true nationally, with median annual earnings for women that were 79% of what men earned.

The 2018 numbers are an improvement over 2010, when women’s median earnings were 81% of men’s in Milwaukee County, 70% in Waukesha County, and 77% nationally.

Although not included in the report, the same data source shows that statewide, 2018 median earnings for women were 78.7% of men’s, Mueller tells the Wisconsin Examiner — relatively close to the 2018 national gap.

Because it includes only full-time workers, the report acknowledges that including part-timers might show larger gaps between women and men because women are more likely to work part time.

“We hear a lot about younger women outpacing men now” in college attainment, Peterangelo says. But, he adds, “despite that, to see the gap in earnings that they do have, I thought was striking.”

“National data show the gender pay gap exists across all racial and ethnic groups,” the report states. Because median earnings are lowest overall for Black, Latina and Native American women, “closing the gap will be particularly challenging for those populations.”

While Milwaukee County women might get paid closer to what men do on average than elsewhere, there’s a downside to that: The smaller gap “appears influenced more by relatively low earnings among men than particularly high earnings among women,” the report states.

In 2018, men in Milwaukee County on average earned 8% less than they did nationally, according to the report, while women in the county were just 1% behind women nationally. Meanwhile, in Waukesha County, although women’s average earnings were farther behind those of men, both genders had higher earnings than their Milwaukee County or national counterparts.

For Waukesha County women, the average annual earnings were $52,298. “Men in Milwaukee County have median earnings that are less than those for women in Waukesha County,” Mueller says.

Mapping the disparities

National studies have uncovered several reasons that women on average earn less than men. In Milwaukee County, the WPF report found, women are a much higher proportion of the workforce for lower-wage occupations than they are for higher-wage ones.

“These occupational differences are influenced both by individual choices and by social forces that shape what women (and men) perceive to be appropriate career options,” the report states. “Pay differences by occupation also may themselves be influenced by whether an occupation has been dominated by women versus men, with female-dominated occupations often paying less.”

Additionally, Peterangelo and Mueller found that Milwaukee County women’s median earnings within each of 23 occupational categories were lower than men in those fields, although the pay differences may vary from group to group.

Among fields where women aren’t widely represented to begin with — including the legal professions, construction and protective services such as firefighting, police work and corrections — women on average also earned less than 70% of what men in those fields earned. And women were less likely to be found in the highest-paid jobs in all fields — for example, as judges in the legal profession.

In management, which employs large numbers of women, their median earnings is 80% of their male counterparts in the county. “One explanation for this is that although women are equally represented in management occupations overall, they account for only 37% of those in top executive positions, which pay the highest salaries,” the report states.

Fields that employ larger numbers of women, pay relatively well and have smaller gaps between women and men include healthcare, media and the arts.

Minding the gap

Other researchers, the report notes, have identified additional factors behind the gender pay gap. They include that women more than men, whether by choice or not, spend more time than men away from work to act as caregivers for children, parents or others. They might work part-time, have gaps in their careers, or take jobs that offer more schedule flexibility than found in some higher-paying jobs.

The pay gap between men and women will “diminish slowly but… endure well into the future” under current trends, the report says. But while the researchers don’t make specific recommendations, they do identify policy changes that could close the gap more quickly. Those include more flexible schedules in a wider range of occupations and expanded access to paid family leave and to quality affordable child care.

The COVID-19 pandemic might lay the groundwork for those and other changes, but it could also stall it.

“The COVID situation has exposed some of the disparities, including women being more likely to lose jobs than men,” Peterangelo says. The availability of child care, he adds, has been among the complications of trying to reopen the economy.

“Hopefully, it points to the need for changes. But it could actually, in the short term, be more challenging for businesses to provide additional benefits.”

“The situation is so new,” adds Mueller. “There’s a thought that it could help in normalizing these [more flexible] work arrangements. But it could also be damaging. We just don’t know yet.”

Reprinted with permission of Wisconsin Examiner.