The Republicans’ Gerrymander Scheme

The polls, the data, the legalities. How Robin Vos hopes to triumph.

In recent weeks there has been widespread speculation that the Republican-dominated Legislature would try to exclude Governor Tony Evers from a say in redistricting the state following the 2020 census. GOP legislators would do this by passing revised districts in a joint resolution from the state Assembly and Senate rather than a bill. Unlike a bill, a joint resolution cannot be vetoed by the governor.

It is not clear which side originated this rumor. In late July of last year the liberal Wisconsin Examiner published an article discussing the joint resolution possibility:

Advocates on both sides of recent redistricting battles in Wisconsin have told the Examiner they believe that the Republican-controlled legislature might draw new, gerrymandered voting maps after the 2020 census, using a process that would avoid sending the plan to Democratic Gov. Tony Evers for his signature or veto.

The Examiner raised the possibility that the Wisconsin Institute for Law & Liberty would back such a move, quoting WILL president Rick Esenberg saying he understands the argument that the constitution reserves redistricting to the state Legislature, adding “I don’t think it’s a frivolous argument.” Esenberg further described the joint resolution idea as “the only way out of what is an assured impasse.”

A subsequent Journal Sentinel article paints Esenberg as less enthusiastic for a repeat of the secret redistricting process following 2010 census. Noting that Republicans were roundly criticized for this, the article summarizes Esenberg as saying “lawmakers should not do it again.”

Despite the negative public reaction to the 2011 gerrymander, Assembly Speaker Robin Vos seems intent on following the same basic strategy in the coming year. He said he may have members sign secrecy pledges again if attorneys for lawmakers believe it is necessary. According to the Journal Sentinel, he “said lawmakers would follow a ‘normal process’ in line with what they’ve done in the past.”

He blamed “bad candidates” for the Democrats’ lack of success and not the maps.

“This is a clear example of Democrats fielding faulty candidates where their agenda does not appeal to anybody outside big cities like Madison and Milwaukee,” he said on Wisconsin Public Radio.

In that interview, Vos rejected Governor Evers’ plan to establish a nonpartisan commission to recommend new legislative districts: “This is just Democrats rallying their base. This is not something that actually has a huge appeal to anybody outside of the Democrat activists.”

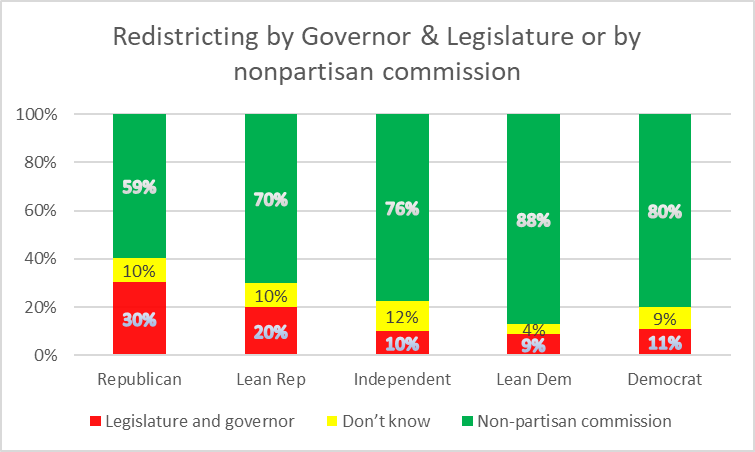

That’s not what polls show. In January 2019, the Marquette Law School Poll asked whether redistricting should be done by the governor and legislature or by a nonpartisan commission. As the next graph shows, the commission was far more popular than the present practice, even among Republicans.

Vos’ attempt to blame bad Democratic candidates is not supported by actual election results. In the 2018 election, Democrat Tony Evers won the election with 50.6 percent of the two-party vote, versus 49.4 percent for Scott Walker, yet Evers won just 36 percent of Wisconsin’s 99 Assembly districts, compared to 63 percent for Walker. The results show that gerrymandering created a majority of districts that are strongly Republican, which makes it easy for most GOP legislative candidates to win.

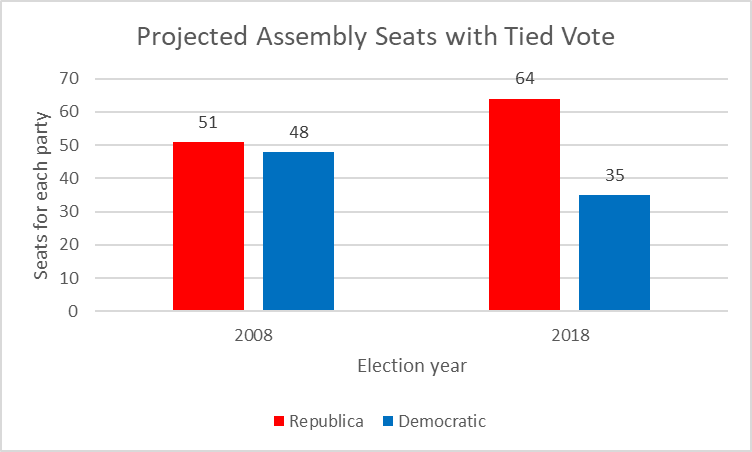

The next chart compares the projected number of districts likely to be won by each party’s candidate in the case of a tied statewide vote before the Republican gerrymander—in 2008–and after—in 2018. The boundaries of the 2008 districts were set by a panel of federal judges. Those in 2018 were set by the Republican legislators and governor.

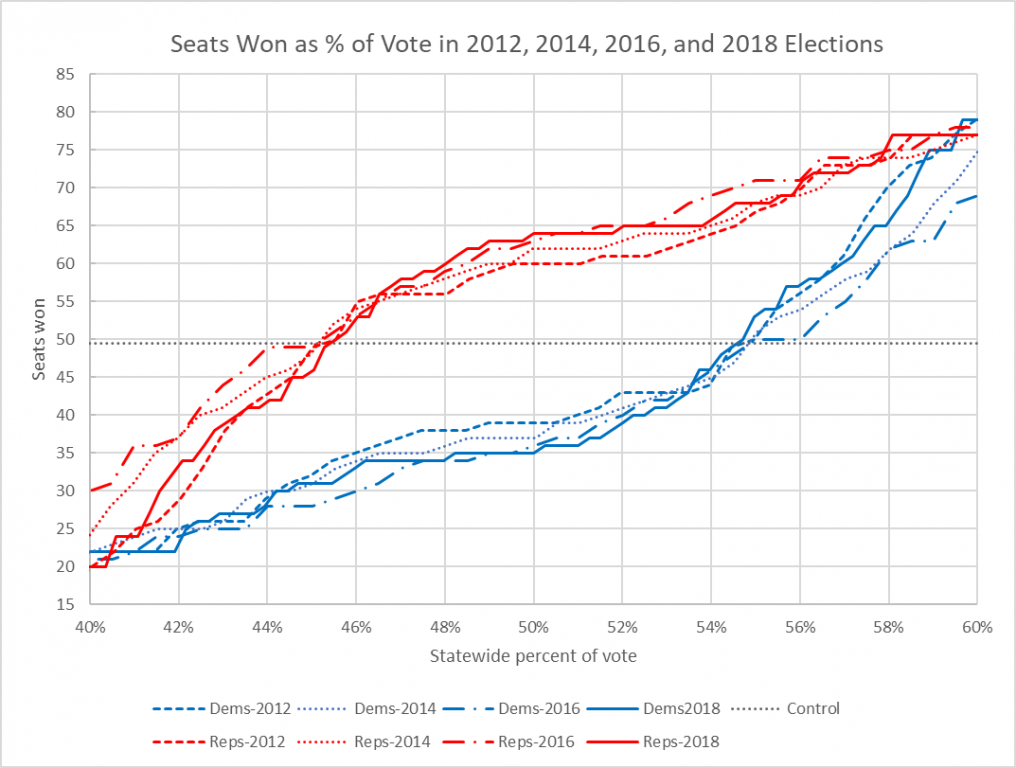

The next chart shows projections of the number of Assembly seats that would have been won by each party based on their statewide vote totals in each of the elections since the 2010 redistricting. Those for 2012 and 2016 are based on the votes for president; those for 2014 and 2018 were based on the race for governor. In all years it shows Republicans winning at least 60 percent of seats with just 50 percent of the total statewide vote.

A test for fairness in redistricting is symmetry: if by winning 53 percent of the vote, for example, Republicans would win 65 seats, then Democrats should win 65 seats with a 53 percent vote share. Instead, they would be projected to win just 41 districts, leaving Republicans thoroughly in control.

Compare this to the 2008 election, as shown below. While not perfectly symmetric (there’s a sight edge for Republicans) it comes close.

The next two charts help explain how the gerrymander worked. The first shows the distribution of districts in 2008, with majority Republican districts on the left in red and Democratic ones (in blue) on the right.

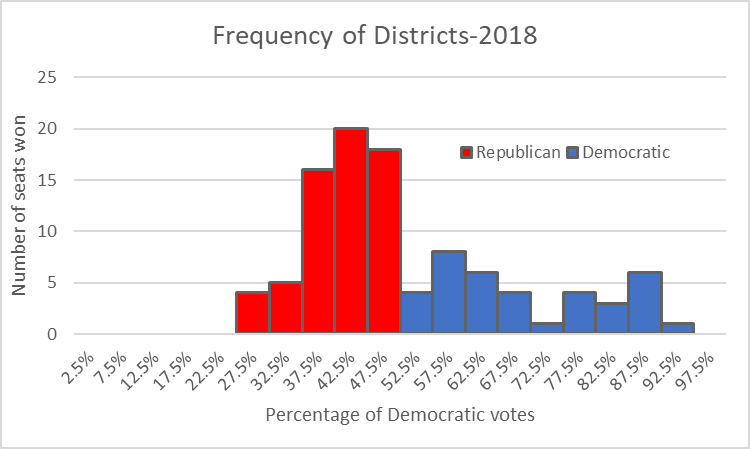

Compare this to the 2018 gubernatorial election. Democratic voters have been “packed” into districts already heavily (62 to 93 percent) Democratic. This allows the “cracking” of districts that previously had a small majority of Democrats and those that were competitive, yielding many new majority Republican districts.

One quick and dirty way to test for gerrymandering is to compare the mean to the median district vote. The median is the midpoint, where half the districts have a larger portion of, say, Republicans and half have fewer. If the mean equals the median, the distribution is symmetric. In the 2018 election, the mean district vote for governor was 49.4% for Walker and 50.6% for Evers. By contrast the median vote was 54.2% for Walker and 45.8% for Evers.

The 2011 redistricting succeeded in its goal of making it practically impossible for Democrats to win the Wisconsin legislature. Although Vos has been cagey about whether he will try to repeat that he seems to be intent in cutting out the governor.

Such an attempt, as Esenberg suggests, starts with a reinterpretation of the language of the state constitution. Article IV Section 17 (2) of the state constitution states that:

No law shall be enacted except by bill.

Article V Section 10 further specifies:

(a) Every bill which shall have passed the legislature shall, before it becomes a law, be presented to the governor.

(b) If the governor approves and signs the bill, the bill shall become law.

Section 3 of Article IV states that:

At its first session after each enumeration made by the authority of the United States, the legislature shall apportion and district anew the members of the senate and assembly, according to the number of inhabitants.

The idea of cutting the governor out of this normal legislative process has come up before: In a 1961 decision, Reynolds v. Zimmerman, the Wisconsin Supreme Court rejected a previous attempt to use a joint resolution process for redistricting. Fundamental to this decision was the consideration that, while individual legislators represented the interests of their districts, only the governor represented the interests of Wisconsin as a whole.

However, the court would face another impediment besides the Reynolds decision. Right now there is a law on the books that redistricted the state. Both 2011 Act 43 (repealing and replacing previous definitions of legislative districts) and 2011 Act 44 (doing the same to Congressional districts) are part of Wisconsin law.

Thus, even if the state Supreme Court decides to reverse its predecessor, it appears that the districts established in 2011 would remain as part of Wisconsin law: It seems doubtful that a joint resolution could repeal and replace an act. Yet if the 2011 districts remained law this would violate the state constitution’s mandate to reapportion the districts every ten years. So how could the Supreme Court, even one so pliant to Republican wishes, justify overriding so much constitutional law?

This appears to be be what Vos, in his eagerness to keep power in Republican hands, is hoping for. It has positioned his Republicans as the enemy of representative government, who would willingly violate the wishes of an overwhelming majority of Wisconsin’s voters.

More about the Gerrymandering of Legislative Districts

- Without Gerrymander, Democrats Flip 14 Legislative Seats - Jack Kelly, Hallie Claflin and Matthew DeFour - Nov 8th, 2024

- Op Ed: Democrats Optimistic About New Voting Maps - Ruth Conniff - Feb 27th, 2024

- The State of Politics: Parties Seek New Candidates in New Districts - Steven Walters - Feb 26th, 2024

- Rep. Myers Issues Statement Regarding Fair Legislative Maps - State Rep. LaKeshia Myers - Feb 19th, 2024

- Statement on Legislative Maps Being Signed into Law - Wisconsin Assembly Speaker Robin Vos - Feb 19th, 2024

- Pocan Reacts to Newly Signed Wisconsin Legislative Maps - U.S. Rep. Mark Pocan - Feb 19th, 2024

- Evers Signs Legislative Maps Into Law, Ending Court Fight - Rich Kremer - Feb 19th, 2024

- Senator Hesselbein Statement: After More than a Decade of Political Gerrymanders, Fair Maps are Signed into Law in Wisconsin - State Senate Democratic Leader Dianne Hesselbein - Feb 19th, 2024

- Wisconsin Democrats on Enactment of New Legislative Maps - Democratic Party of Wisconsin - Feb 19th, 2024

- Governor Evers Signs New Legislative Maps to Replace Unconstitutional GOP Maps - A Better Wisconsin Together - Feb 19th, 2024

Read more about Gerrymandering of Legislative Districts here

Data Wonk

-

Why Absentee Ballot Drop Boxes Are Now Legal

Jul 17th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

Jul 17th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

-

The Imperial Legislature Is Shot Down

Jul 10th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

Jul 10th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

-

Counting the Lies By Trump

Jul 3rd, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

Jul 3rd, 2024 by Bruce Thompson