The Icehouses of Old Milwaukee

Two were run by breweries on the Milwaukee River. Fragments of them still can be found.

This century-old partially collapsed timber dam across the Milwaukee River north of Locust Street is all that remains of the Schlitz Brewing Company’s ice-harvesting operation in Milwaukee’s Riverwest neighborhood. Photo by Carl Swanson.

There is a fascinating reminder of Riverwest’s past hidden in plain sight in the Milwaukee River just north of the Locust Street bridge. Here logs across the river trace the remains of the Schlitz icehouse dam. The dam is over a century old, but the reason for Schlitz building its icehouses here dates back even further – all the way to late 1878 when this area was largely open country.

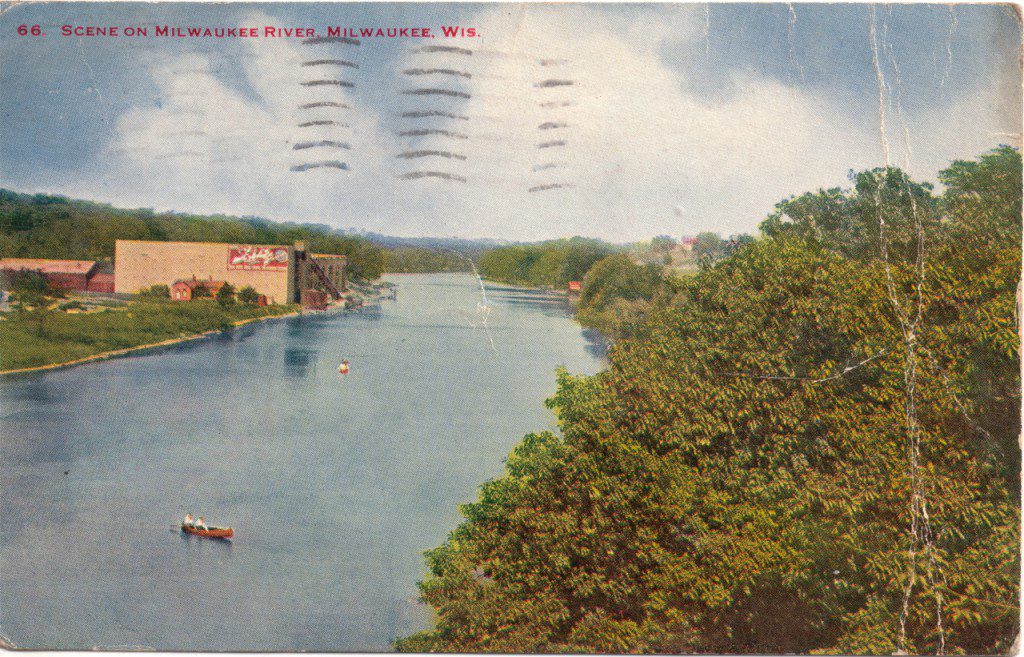

About 100 years ago, as shown in this postcard from the early 1900s, the Schlitz Brewing Company harvested ice from the Milwaukee River and stored it in two large ice houses (at left) located north of Locust Street in Milwaukee’s Riverwest neighborhood. Collection of Carl Swanson.

Ice was an important commodity in the days before commercial refrigeration. It was harvested from the harbor and rivers as early as the 1850s and stored in icehouses for use in the summer months. The ice business grew with the city. By the 1890s, Milwaukee’s annual commercial ice harvest totaled 300,000 tons with the city’s breweries cutting and storing an additional 50,000 tons.

But the problem of water pollution also grew with the city. By the late 1870s, the city’s primitive sewers emptied 100 tons of untreated human and animal waste each day into the Milwaukee River.

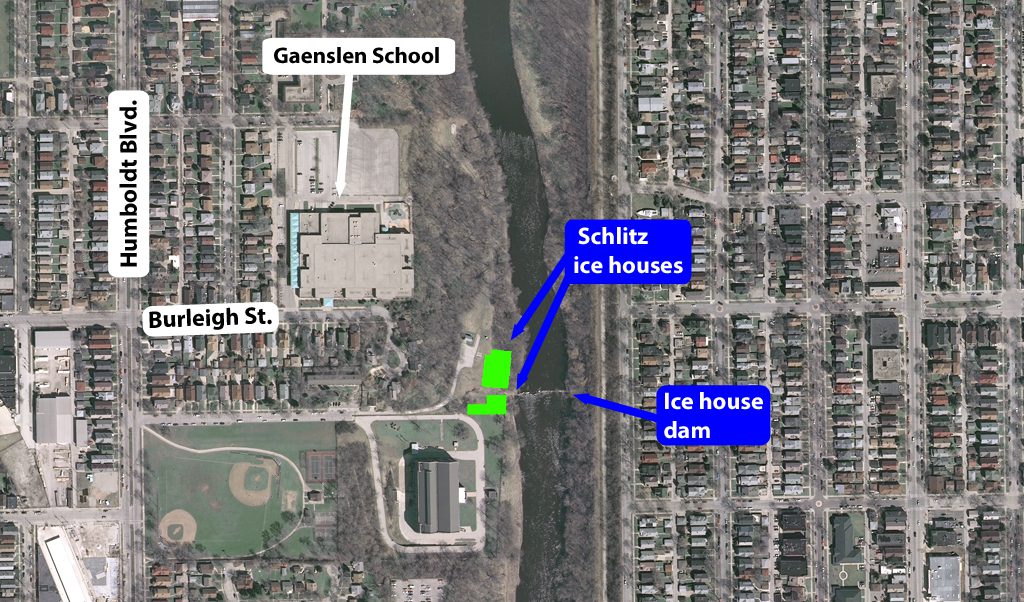

The location of the twin former Schlitz ice houses is overlaid on this modern satellite image. The ice house dam is all that remains today. Illustration by Carl Swanson.

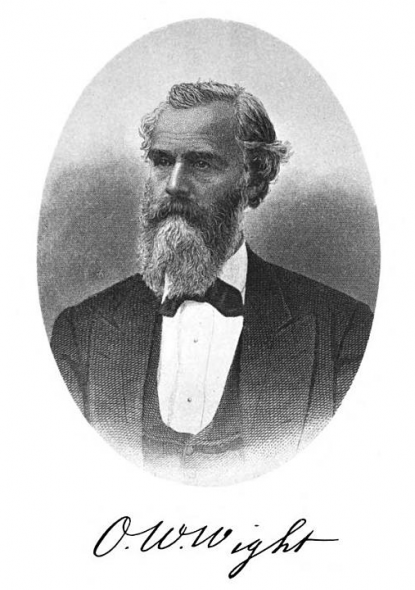

In 1878, appalled by the condition of the rivers and alarmed by the public health implications of waterways that were – at times – equal parts river water and raw sewage, O.W. Wight, Milwaukee’s newly appointed commissioner of health took action.

In his annual report to the mayor and city council, he wrote: “The first sewer to empty into the Milwaukee River is at North Street bridge, some little distance above the dam. Consequently all ice cut for ‘eating and drinking purposes,’ to use the language of the ordinance, must be above North Avenue, so far as the Milwaukee River is concerned.

“Citizens will do well to take note of these geographical limits, and co-operate with the Health Department in order to protect themselves in the future, from eating and drinking a frozen compound of things unpleasant to meditate.”

Even with the new restrictions in place, Wight noted the ice is not likely to be especially pure.

“The Milwaukee River and its branches run a hundred miles through a thickly settled country, containing farms and villages, from which barnyard slops, water fouled by manured

lands, the drainage of privy vaults, of butchers’ shops, of hog pens, etc., flow into the passing streams.”

Still, ice was the only way to prevent food from spoiling in the summer and, before the invention of mechanical ice making, cutting it from the river was the only convenient source. If the ice could not be made absolutely pure, Wight had at least ensured it would be much cleaner than before.

Having dealt with ice for human consumption, Wight turned his attention to ice harvested and used for cooling slaughterhouse meat lockers and brewery storehouses. The rules regarding the purity of cooling ice were much less restrictive than those governing the harvest of ice for consumption. Tougher requirements would require Wright to confront the city’s wealthiest and most powerful business leaders – the owners of Milwaukee’s breweries.

Wight’s message to each was blunt. Meltwater saturated their storage buildings with disease-bearing germs. Even the ice that cooled the kegs in their delivery wagons steadily and daily dripped sewage on streets throughout Milwaukee. Wight told each brewer, “On the lower portions of the rivers, where they receive great volumes of sewage from the city, where the water is foul and stinking with all kinds of abominations, the commissioner would not allow ice to be cut for any purpose whatever.”

The brewery owners took Wight’s message to heart. Not only were they willing to comply, they went the extra mile to secure clean ice for their operations. For example, the Phillip Best Brewing Co. purchased land on Pewaukee Lake where it built an icehouse and railroad siding to supply the several breweries it operated.

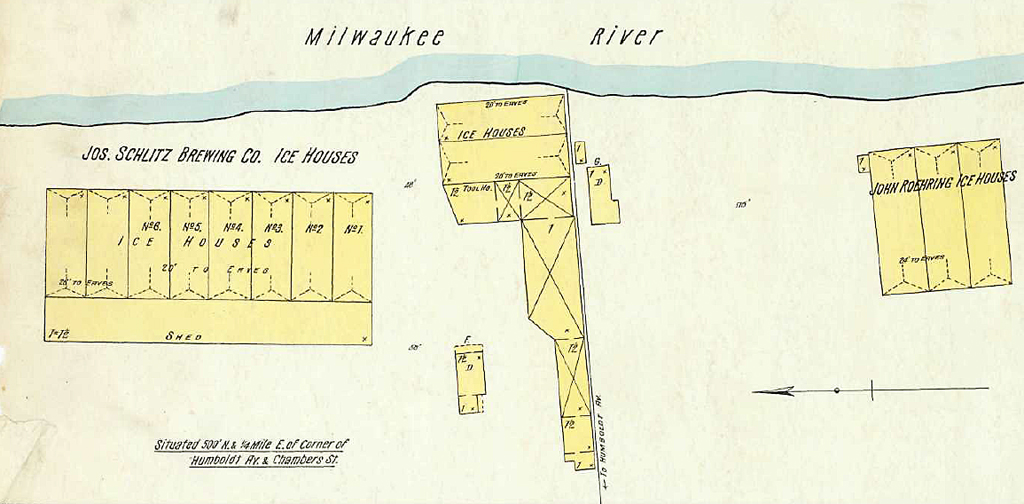

The group of Riverwest icehouses, located on the river at the foot of East Chambers Street, include the Schlitz complex, center and left, and a commercial ice dealer to the right. The municipal pumping station, located between the two sites, had not yet been built when this fire insurance diagram was drawn in 1894.

The Schlitz Brewing Company, for its part, established large ice houses on the west bank of the Milwaukee River, about midway between North Avenue and Capitol Drive. To ensure a suitably wide “ice field” when the harvesting time rolled around, Schlitz constructed a low timber dam across the river.

The dam was built a century ago to ensure a good ice harvest for a pair of Schlitz ice houses once located on the far bank. Photo by Carl Swanson

To the south, nearly under today’s Locust Street bridge, a commercial dealer, John Roehring also built an icehouse. This soon came under the ownership of the Random Lake Ice Co. In the winter of 1914, it was totally destroyed by a fire. A news item from the time suggested the fire was set by tramps trying to keep warm.

Random Lake rebuilt on the same site. Its new icehouse measured 180 x 120 feet and was 40 feet tall. It remained part of Riverwest until fall 1954 when it was once again the victim of a fire.

Broken concrete near the Locust Street bridge marks the location of Random Lake Ice Co. ice house, destroyed in a spectacular blaze 60 years ago. Photo by Carl Swanson.

Leased by Blatz Brewing Co. at the time of the blaze and used as a warehouse, the building and the 600,000 cases of empty bottles it contained were total losses. Bulldozers had to be called in to level the mass of melted glass and charred wood.

It is not known when the Schlitz icehouses were demolished and no trace of them can be found on the riverbank. However, a great deal of rubble marks the site of the Random Lake Ice Co., although you have to push your way through dense undergrowth to find it.

Stretching across the river, through a century of freezes, thaws, and floods, sections of Schlitz’s ancient timber dam remain.

The east end of the Schlitz icehouse dam features this timber spillway, partially intact despite 100 years of floods and freezes. Photo by Carl Swanson.

Carl Swanson is the author of the book Lost Milwaukee from The History Press, available from book stores or online.

Lost Milwaukee

-

When Police Handed Out Courtesy Cards

Jul 14th, 2020 by Carl Swanson

Jul 14th, 2020 by Carl Swanson

-

Riverwest Had World’s Largest Color Printing Press

Jun 11th, 2020 by Carl Swanson

Jun 11th, 2020 by Carl Swanson

-

The Mighty Grand Avenue Viaduct

Apr 29th, 2020 by Carl Swanson

Apr 29th, 2020 by Carl Swanson

Another fascinating bit of Milwaukee history. Thanks Carl!

The article includes a quote from 1878 which mentions both the “North Street Bridge” and “North Avenue” suggesting that “North Street” and “North Avenue” were different streets.

Many Milwaukee streets were renamed in the 1920s (when Grand Avenue became West Wisconsin Avenue, for instance; wasn’t East Wisconsin originally named Spring Street?) and I wonder if “North Street” became something else (like Humboldt).

@TransitRider

North Avenue was originally called North Street.

West Wisconsin Avenue was originally called Spring Street. In 1876 it was changed to Grand Avenue, then to Wisconsin Avenue in 1926.

East Wisconsin Avenue was originally called Wisconsin Street. It was changed in 1926.

Carl, thanks!

Do you know what kind of North Avenue bridge was around in 1878? Was made of steel or wood? (I doubt that concrete was an option back then.) Was it high (like today’s bridge) or low (like Humboldt)?

@TransitRider,

I do not know about the bridge. Perhaps Carl Swanson can answer that.