How a Riverside Roadway Was Stopped

It was all because of the picture-postcard 1927 Capitol Drive Bridge.

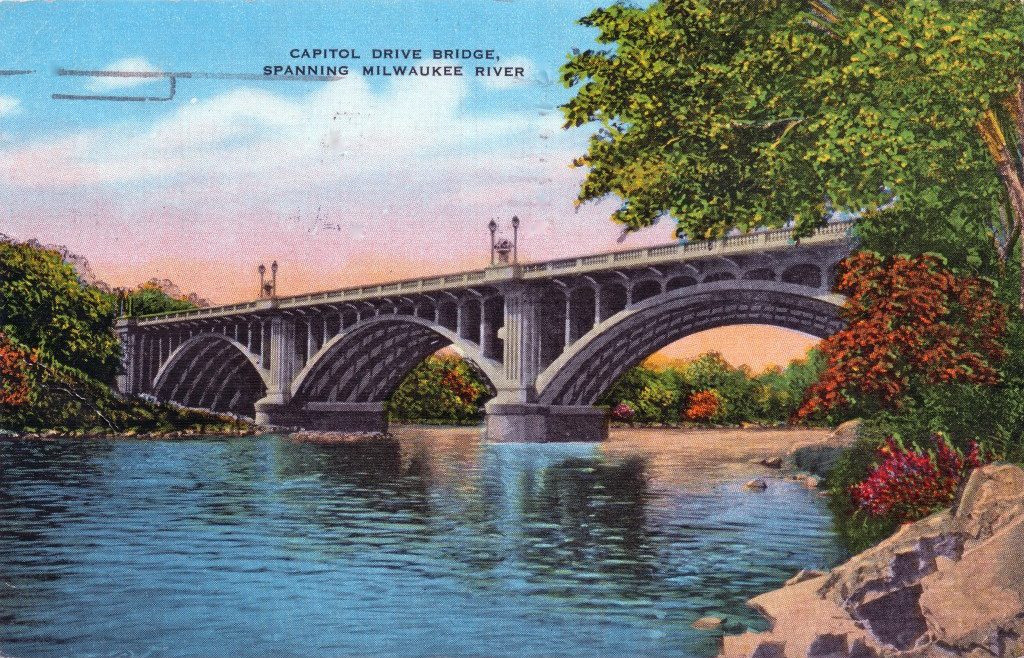

Spanning 532 feet and requiring more than 20,000 tons of concrete, the former Capitol Drive bridge over the Milwaukee River was an imposing structure. The bridge was built in 1927. This postcard was mailed in 1946. Carl Swanson collection

Vintage postcards can be odd. Why on earth would a visitor send the folks back home this postcard of the 1927 Capitol Drive bridge?

Before answering that question, there’s a funny thing about this bridge. In a roundabout way, it saved part of the Milwaukee River from being filled in for a riverside roadway.

The planned first section extended north from the foot of East Menlo Boulevard, (basically today’s Hubbard Park), under the Capitol Drive bridge, to a junction 300 feet north of the bridge with the Milwaukee County parkway through Estabrook Park.

Shorewood Village Manager Harry Schmitt told the Milwaukee Journal he hoped the city of Milwaukee would soon follow suit and build a river drive of its own connecting the Shorewood portion of the road southward along the water’s edge to Riverside Park and a connection with East Newberry Boulevard.

In 4 to 5 years, he confidently predicted, motorists would be able to cruise alongside the Milwaukee River for several miles. The road, Schmitt added, was the only way to give the public the benefit of the use of the riverbank.

Schmitt clearly believed filling in a big chunk of the river for a new road was completely reasonable and no opposition could arise.

He was mistaken.

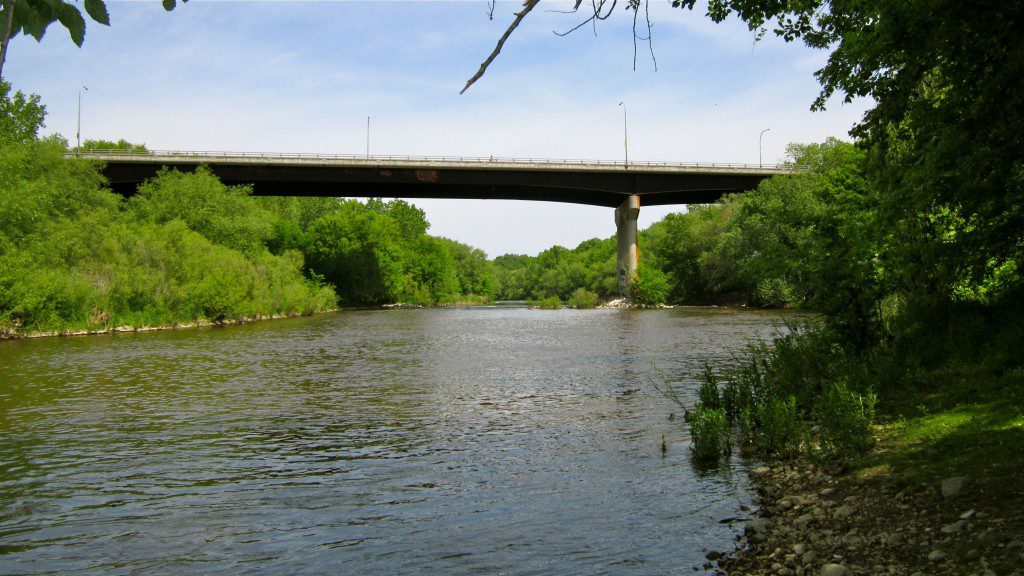

The current Capitol Drive bridge is nothing to write home about. On the other hand, if Shorewood’s plans had gone through, this picture would have been taken from the middle of a two-lane road. Photo by Carl Swanson.

Just four days later, Schmitt received a phone call from the state Public Service Commission ordering the village to cease dumping fill in the river. The action followed a joint protest filed with the PSC by Milwaukee city and county officials. They pointed out Shorewood’s village limits extend only to the natural east bank of the Milwaukee River and not to the center of the stream, as might normally be expected where two communities meet at a river. In other words, since the entire width of the riverbed is inside Milwaukee’s city limits, Shorewood was dumping fill outside of its jurisdiction.

Ironically, it was Shorewood’s own action in an earlier dispute that may have doomed its river roadway.

When the 1927 Capitol Drive bridge was in its planning stages (it replaced a spindly steel truss contraption so narrow there was scarcely room for two vehicles to pass), the city of Milwaukee asked Shorewood to share the cost. The village categorically refused, pointing to its founding charter that set the community’s boundary at the water’s edge and included no part of the river itself.

To Shorewood’s dismay, Milwaukee remembered this piece of historical trivia and turned it against the village four years later.

Getting back to the original question: Why were postcard buyers attracted to views of bridges? We usually think of bridges—if we think of them at all—as utilitarian ways to get from here to there.

In 1927 people would have seen things differently. The new Capitol Drive really was a marvel. Not because it cost a jaw-dropping $400,000 in pre-depression dollars and not because it took 20,000 tons of cement to build, but because it connected the entire north side of Milwaukee with the entire North Shore by way of an impressively long, wide, and elegant piece of engineering.

They were seeing the big picture. That’s certainly worth the price of a postcard, even if all you could fit on the back is, “Having a great time in Milwaukee, wish you were here.”

Carl Swanson is the author of the book Lost Milwaukee from The History Press, available from book stores or online.

Lost Milwaukee

-

When Police Handed Out Courtesy Cards

Jul 14th, 2020 by Carl Swanson

Jul 14th, 2020 by Carl Swanson

-

Riverwest Had World’s Largest Color Printing Press

Jun 11th, 2020 by Carl Swanson

Jun 11th, 2020 by Carl Swanson

-

The Mighty Grand Avenue Viaduct

Apr 29th, 2020 by Carl Swanson

Apr 29th, 2020 by Carl Swanson

Really enjoy reading Carl Swanson’s historical pieces. Hope for more to come!

This is excellent, Thanks, Carl!