Gerrymandering Is Built on Lies

Which is why the North Carolina plan was overruled. Wisconsin’s is very similar.

The title of associate US Supreme Court Justice Neil Gorsuch’s recently issued book echoes Benjamin Franklin’s supposed answer to a woman who asked what the Constitutional Convention had adopted: “A Republic, If You Can Keep It.” This suggests that Gorsuch thinks that our republican form of government is important. Yet in joining the 5-4 majority that voted in favor of allowing partisan gerrymanders, Gorsuch voted against one of the crucial underpinnings of democracy, allowing citizens to choose their leaders.

Two recent court decisions about gerrymandering in North Carolina dealt with a very similar set of facts, but came to very different conclusions. In each, Common Cause and others challenged redistricting plans written by Republican legislators to guarantee that Republicans would win a majority of seats even while losing the popular vote.

The first case, Rucho v. Common Cause, challenged redistricting of North Carolina’s US House seats in federal courts (and a Democratic gerrymander in Maryland). The second, Common Cause v. Lewis, challenged the Legislature’s redistricting of itself in the state courts.

Despite their similarities the two cases had very different outcomes. Writing for a 5-4 majority US Chief Justice John Roberts concluded that the federal courts had no business interfering with gerrymandering schemes. In doing so, Roberts and his colleagues killed the challenge to Wisconsin’s Republican gerrymander.

In the other case a three-judge state panel gave the North Carolina Legislature two weeks to create districts in which “partisan considerations and election results data shall not be used.”

Despite conceding that “these cases involve blatant examples of partisanship driving districting decisions,” Roberts concluded that the federal judiciary had no role to play.

… we have no commission to allocate political power and influence in the absence of a constitutional directive or legal standards to guide us in the exercise of such authority.

Roberts goes on to reassure those concerned about democracy that “our conclusion does not condone excessive partisan gerrymandering” and does not “condemn complaints about redistricting to echo into a void.” But he offers no remedy, instead suggesting that state courts or legislation introduced in Congress repeatedly but unsuccessfully might solve the problem.

Article IV, Section 4 of the US Constitution, the so-called “Guarantee Clause,” states that the “United States shall guarantee to every State in this Union a Republican Form of Government.” Contrary to the apparent belief of Republican legislators in North Carolina (and Wisconsin), this does not require state governments dominated by the Republican Party. According to the (very conservative) Heritage Foundation, this requires three elements–popular rule, no king, and the rule of law. By allowing those in power to entrench themselves, gerrymandering undermines at least the first of these.

In its 357-page decision the North Carolina panel of trial court judges takes a very different route:

The issue before the Court is distilled to simply this: whether the constitutional rights of North Carolina citizens are infringed when the General Assembly, for the purpose of retaining power, draws district maps with a predominant intent to favor voters aligned with one political party at the expense of other voters, and in fact achieves results that manifest this intent and cannot be explained by other non-partisan considerations.

It finds that the General Assembly had a partisan intent to create legislative districts that perpetuated a Republican-controlled General Assembly, that it deployed this intent with “surgical precision” to use packing and cracking to dilute Democratic voters’ collective voting strength, that partisan intent predominated over all other redistricting criteria, and that the effect of these maps is that, in all but the most unusual election scenarios, the Republican party will control a majority of both chambers of the General Assembly.

Quoting the US Supreme Court’s observation that “state constitutions can provide standards and guidance for state courts to apply,” the North Carolina court proceeds to decide the case based on the North Carolina constitution. Noting that Section 10 of the state constitution requires that “all elections shall be free, it goes on:

This Court further concludes that the 2017 Enacted Maps are tainted by an unconstitutional deprivation of all citizens’ rights to equal protection of law, freedom of speech, and freedom of assembly.

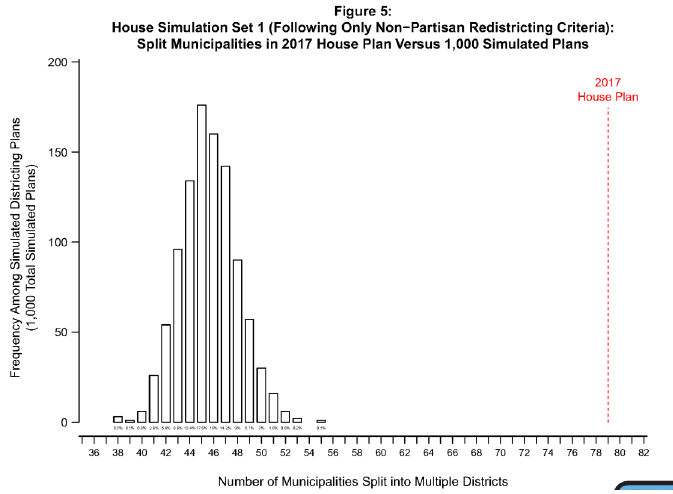

In contrast to the indifference that Roberts and company show to measuring partisan intent, the state judges do a deep dive into statistics. Figure 5, reproduced below, is an example. North Carolina law, like many other states including Wisconsin, requires that map makers minimize the splitting of political units. Jowei Chen of the Department of Political Science at the University of Michigan used mapping software to generate 1,000 district plans based on non-partisan criteria. As can be seen, the adopted plan splits far more municipalities than would be expected. In other words, in order, to make the plan so favorable to Republicans, the map-makers had to do violence to the principle of keeping together people in the same town.

House Simulation Set 1 (Following Only Non-Partisan Redistricting Criteria): Split Municipalities in 2017 House Plan Versus 1,000 Simulated Plans

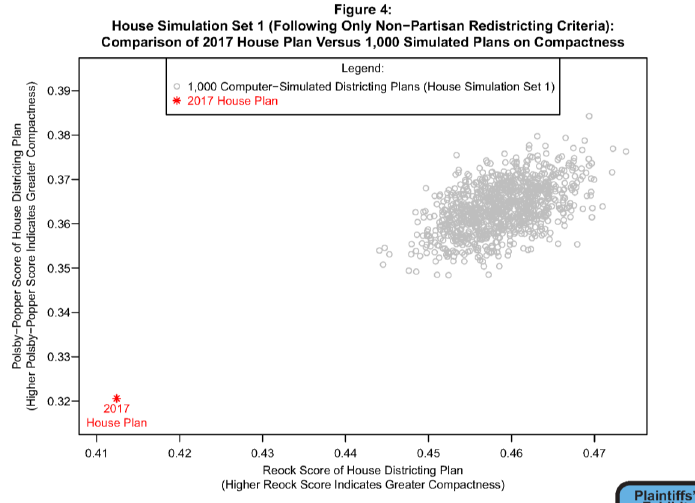

Compactness is another common requirement, including in North Carolina and Wisconsin. There are a number of formulas of measuring compactness, but they generally operate by comparing the area enclosed to the length of its boundary. Two commonly used measures are the Polsby-Popper and Reock compactness scores. Using either formula, a circle—the most compact possible shape—earns a score of one. The less compact a shape is, the smaller its score.

Figure 4, also by Chen, plots the average compactness using the two measures—the Polsby-Popper on the vertical scale and the Reock on the horizontal. The 2017 House Plan (in red on the lower left) is compared using the two measures to the compactness in the 1,000 computer-generated plans (the cloud on the upper right). Again, the House Plan is an extreme outlier, demonstrating the amount of compactness its designers had to sacrifice to gain the plan’s Republican advantage.

House Simulation Set 1 (Following Only Non-Partisan Redistricting Criteria): Comparison of 2017 House Plan Versus 1,000 Simulated Plans on Compactness

As already noted, the North Carolina decision comes from a panel of trial judges, not the state’s supreme court. Theoretically, then, the Republican legislators could appeal it, but they have announced that they will not. Why? Speculation is that they fear losing the appeal, and that such a decision could become a precedent for a state challenge to the Republican gerrymander of the state’s congressional delegation.

The North Carolina judges note that defenders of the gerrymander lied to them:

The Court is troubled by representations made by Legislative Defendants, or attorneys working on their behalf, in briefs and arguments … and to General Assembly colleagues at committee meetings that affirmatively stated that no draft maps had been prepared even as late as August 4, 2017.

This pretense was punctured when Republican consultant Thomas Hofeller died, and his files were leaked. Among other disclosures were the records of his extensive work making the North Carolina plan as Republican-favorable as possible.

This pattern of lying to judges seems to be a pattern among gerrymander defenders. The North Carolina judges point to the contradictory testimony of Thomas Brunell, a Republican expert witness. His argument defending the North Carolina plan contradicted his testimony in Nevada attacking a plan passed by Democrats.

Lying was also associated with Wisconsin’s gerrymander. Under Gov. Scott Walker and Attorney General Brad Schimel, the state’s brief falsely claimed that the bias against Democrats was a byproduct of Democrats’ tendency to live in cities. The evidence showed otherwise, especially when a hard drive was recovered that showed a series of draft plans, each more Republican-friendly than the last.

Chief Justice John Roberts’ decision in Rucho is particularly unfortunate coming at a time when federal district courts were becoming increasingly comfortable with protecting democracy by invalidating gerrymanders. Before Roberts’ decision, the courts ruled against gerrymanders in Maryland, Michigan, North Carolina, Ohio and Wisconsin. No court upheld them.

North Carolina joins Florida and Pennsylvania where state courts ruled against gerrymandering based on provision of their state constitution. Could Wisconsin follow suit? Our constitution lacks the “equal protection” and “free election” clauses similar to North Carolina’s. But it does refer to “governments … deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.” And Section 22, Maintenance of free government. notes that “The blessings of a free government can only be maintained by a firm adherence to justice, moderation, temperance, frugality and virtue, and by frequent recurrence to fundamental principles.”

A state supreme court committed to democratic government, could use these to ban gerrymandering. Unfortunately, there is no reason to expect that the present Wisconsin Supreme Court will move beyond partisanship based on its recent decisions.

Another route against Wisconsin gerrymandering could rest on the constitution’s requirements for districts:

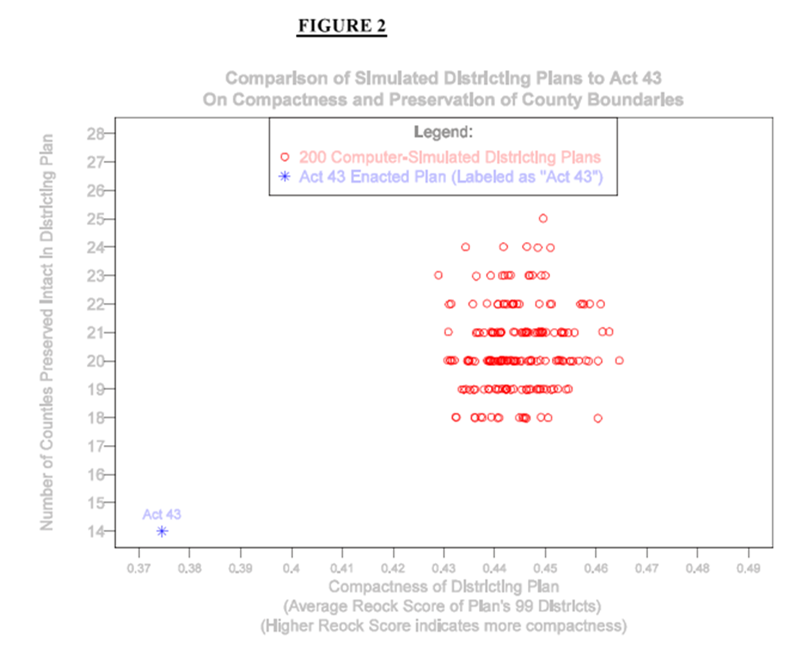

such districts to be bounded by county, precinct, town or ward lines, to consist of contiguous territory and be in as compact form as practicable.

As in North Carolina, the Wisconsin gerrymander sacrificed compactness and divided communities on the altar of partisan advantage. The following graph, taken from Chen’s amicus brief in the challenge to the Wisconsin gerrymander, plots the number of intact counties on the vertical scale against the average compactness on the horizontal. The red circles show the values for 200 computer generated plans. The results of Act 43 are shown at the lower left, again showing the Republican plan is an extreme outlier

Comparison of Simulated Districting Plans to Act 43 on Compactness and Preservation County Boundaries

Unfortunately, with the US Supreme whiffing on gerrymandering and the Wisconsin Supreme Court dominated by partisan hacks, the 2020 election becomes all the more important.

More about the Gerrymandering of Legislative Districts

- Without Gerrymander, Democrats Flip 14 Legislative Seats - Jack Kelly, Hallie Claflin and Matthew DeFour - Nov 8th, 2024

- Op Ed: Democrats Optimistic About New Voting Maps - Ruth Conniff - Feb 27th, 2024

- The State of Politics: Parties Seek New Candidates in New Districts - Steven Walters - Feb 26th, 2024

- Rep. Myers Issues Statement Regarding Fair Legislative Maps - State Rep. LaKeshia Myers - Feb 19th, 2024

- Statement on Legislative Maps Being Signed into Law - Wisconsin Assembly Speaker Robin Vos - Feb 19th, 2024

- Pocan Reacts to Newly Signed Wisconsin Legislative Maps - U.S. Rep. Mark Pocan - Feb 19th, 2024

- Evers Signs Legislative Maps Into Law, Ending Court Fight - Rich Kremer - Feb 19th, 2024

- Senator Hesselbein Statement: After More than a Decade of Political Gerrymanders, Fair Maps are Signed into Law in Wisconsin - State Senate Democratic Leader Dianne Hesselbein - Feb 19th, 2024

- Wisconsin Democrats on Enactment of New Legislative Maps - Democratic Party of Wisconsin - Feb 19th, 2024

- Governor Evers Signs New Legislative Maps to Replace Unconstitutional GOP Maps - A Better Wisconsin Together - Feb 19th, 2024

Read more about Gerrymandering of Legislative Districts here

Data Wonk

-

Life Expectancy in Wisconsin vs. Other States

Dec 10th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Dec 10th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

-

How Republicans Opened the Door To Redistricting

Nov 26th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Nov 26th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

-

The Connection Between Life Expectancy, Poverty and Partisanship

Nov 21st, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Nov 21st, 2025 by Bruce Thompson