High CEO Pay Due to Stock Buybacks?

It’s definitely one cause. It may also make the American economy less productive.

When corporations report their financial results, they subtract their expenses from their revenues to get their net income. Traditionally, net income has two uses. Part can be sent to the firm’s shareholders as a dividend. The remainder is reinvested in the business, for instance by supporting research, adding to or improving the firm’s facilities or developing new products. This year’s retained earnings are added to those from previous years to calculate the shareholders’ equity.

Recently a third use of net income has grown increasingly popular, variously called “stock buybacks” or “share repurchases.” The firm buys back shares of its own stock, thus reducing the number of outstanding shares. As a result, each remaining shareholder owns an increased portion of the firm.

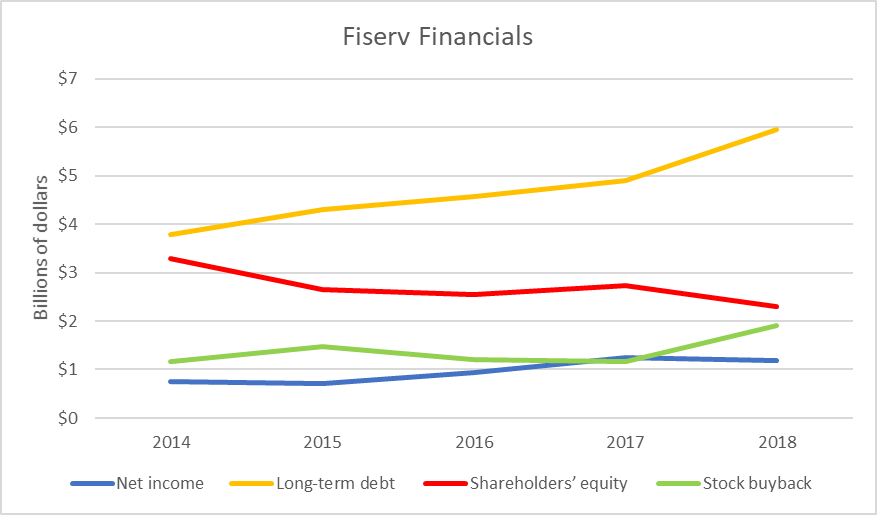

Fiserv, based in Brookfield, is an example of a firm that has gone all the way in replacing dividends with buybacks. “Our current policy is to use our operating cash flow primarily to fund capital expenditures, for share repurchases, … and acquisitions, and to repay debt rather than to pay dividends.” The results of this strategy, taken from Fiserv annual reports over the past five years is shown in the next graph.

The blue line (in billions of dollars) shows Fiserv’s net income over the period. The green line shows the funds used to repurchase company stock. Note that in most years, money spent buying stock actually exceeded net income.

How did Fiserv manage this trick? The answer lies in the other two lines. As shareholder equity (in red) went down, Fiserv filled the gap by borrowing more (in yellow). In five years, Fiserv’s financing went from about equal proportions of debt and equity to 72 percent debt and 28 percent equity.

Fiserv is the only one of the six Milwaukee-based companies that Urban Milwaukee’s Bruce Murphy singled out in his article on executive compensation that got rid of dividends entirely. By contrast, Wisconsin Energy was the only firm on his list that did not repurchase its own stock.

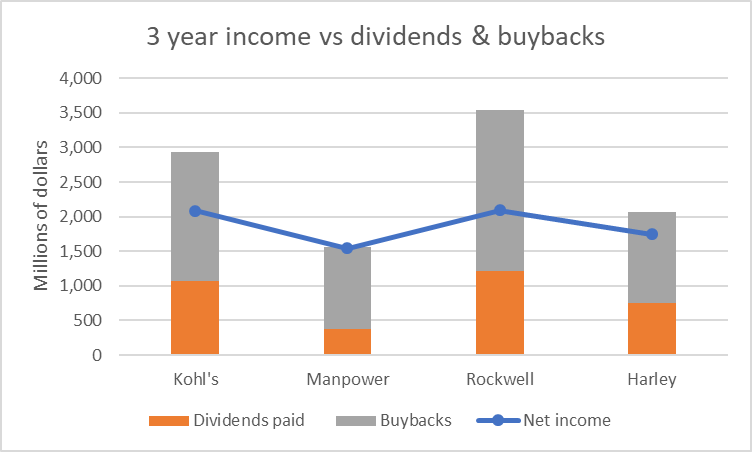

The other four companies both issued dividends and bought back stock, as shown in the next graph. For three of the firms, total dividends (shown in rust) and buybacks (in gray) over the last three years exceeded the net income. For the fourth company—Manpower—dividends and buybacks consumed all net income. As with Fiserv, any reinvestment in the four firms would require increased debt.

These results are consistent with what the economist William Lazonick reported in a 2014 Harvard Business Review article. According to his calculations, the S&P 500 companies used 54 percent of their earnings to buy back their stock and an additional 37 percent for dividends, leaving less than 10 percent for reinvesting between 2003 and 2012.

Lazonick argues that from the end of World War II until the late 1970s major U.S. corporations followed a “retain-and-reinvest” approach to their profits. On average they reinvested half their profits into areas like research and the development of new products. In 1982, the Securities and Exchange Commission changed the rules so that companies were largely free to buy their own stock. This gave way to a “downsize-and-distribute” regime of reducing costs and then distributing the freed-up cash to financial interests, particularly shareholders. Wisconsin Senator Tammy Baldwin’s Make Work Pay Act, would ban open market stock buybacks.

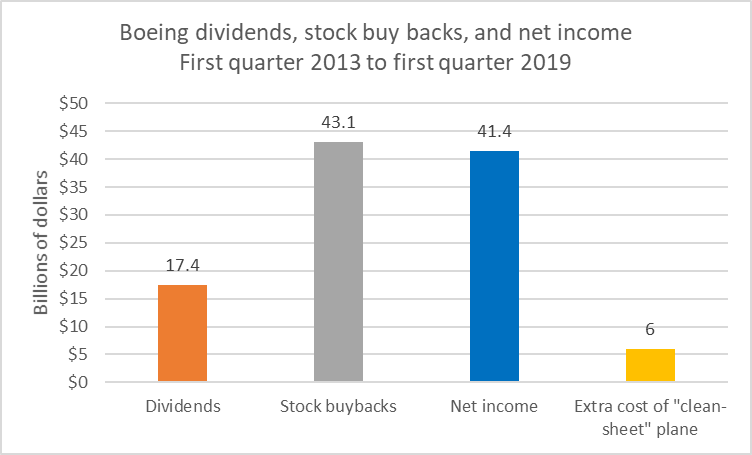

In a recent article, Lazonick suggests that Boeing’s emphasis on stock buybacks could have contributed to the two crashes of its new 737 MAX 8 airplane. As the next graph shows, between 2013 and 2019, Boeing was a very aggressive stock repurchaser, spending more than enough to consume its whole net income. Rather than spend the estimated $6 billion dollars to design a “clean-sheet” airplane from scratch, Boeing decided to add larger engines to an earlier design. This created a possible instability which Boeing attempted to prevent through a software fix. Indications are that the two crashes were caused by faulty sensor feeding false data to the software, causing the plane to plunge downward.

Advocates of stock buybacks make several points in their favor: that buybacks increase shareholder value by signaling that management believes their shares are undervalued, that they return cash to shareholders who sell their shares back to the firm, and that they benefit shareholders who end up with a greater proportion of the stock. What is clear, from the Fiserv example, however, is that they increase debt and financial leverage at companies.

If I am convinced that a stock will rise 10 percent, I can double my return to 20 percent by borrowing half the money and buying twice as much stock. That is the power of leverage. Of course, leverage works in reverse: if I am wrong and the stock price goes down, leverage doubles my loss. Thus, leverage amplifies both good outcomes and bad outcomes.

By the same token, if companies become more leveraged as the result of share buybacks, particularly if increased debt is used, they become more vulnerable to downturns. Their lenders are also subject to more risk and are likely to Increase interest rates to compensate.

However, this example, rather than proving the advantage of buybacks, simply makes the noncontroversial point that bad investment decisions should be avoided. If management has run out of productive uses of net income, a more interesting example would compare buybacks to dividends. With dividends, shareholders choose what to do with the money. Those who are optimistic about the firm can buy more of its stock. Those pessimistic about the firm can invest the dividend elsewhere. With buybacks, management chooses; with dividends, the shareholder decides.

That difference helps explains the growing popularity of buybacks. A growing portion of executive compensation is based on so-called “long-term incentive programs,” which, despite their name, are often heavy with short-term financial measures. One is earnings per share (EPS). By reducing the number of shares, buybacks increase EPS, at least in the short run. Likewise, share repurchases reduce the company’s cash holdings, and consequently its total asset base, by the amount of cash expended in the buyback, leading to higher return on assets (ROA).

The increasing popularity of buybacks helps explain recent increases in executive compensation, largely unconnected to company success. Thus, they may be a factor in growing inequality in our society.

Stock buybacks, by absorbing retained earnings, may also have the effect of making firms less aggressive in pursuing research, developing new products, or finding improvements, contributing to the sluggishness of the American economy in its recovery from the Great Recession.

Data Wonk

-

Life Expectancy in Wisconsin vs. Other States

Dec 10th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Dec 10th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

-

How Republicans Opened the Door To Redistricting

Nov 26th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Nov 26th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

-

The Connection Between Life Expectancy, Poverty and Partisanship

Nov 21st, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Nov 21st, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

The highly leveraged stocking buying during the 1920s ended disastrously in the fall of 1929. Yet, here we are again, playing with the same match the started the Great Depression. As in the 1920s, the federal government is complicit. The so called tax reform has only added to the problem. Like the 1920s, problems with corporations are not the result of labor unions. Rather they are the result of mismanagement and greed on the part of overpaid executives. This will end badly for this country, just as it did 90 years ago.

There is one big difference between leveraged stock purchases in the 1920s and today.

Back then it was common to pay only 10% of the stock price and borrow the remaining 90%. A mere 10% drop in the stock price meant the entire arrangement unraveled.

Today, you must pony up at least 50% of the stock price (it is illegal to finance more than 50% of a stock purchase) which means that stock prices would have to drop 50% before things would unravel today.