40 Years of Fighting for Consumers

Citizens Utility Board celebrates 40th birthday, still pushing for lower utility rates, consumer rights.

In 1979, Wisconsin Gov. Lee Sherman Dreyfus signed the bill that created the Citizen Utility Board. Others pictured include Lorraine Barniskis, policy director for House Majority Leader Jim Wahner; Rep. Wayne Wood; Rep. Wahner; Sen. Joe Strohl; Rep. John Norquist; Sen. David Berger; and Senate Majority Leader Bill Bablitch. Photo courtesy of the Wisconsin Citizens Utility Board.

As a wave of consumer activism swept the country in the 1970s, Wisconsinites formed the country’s first statewide consumer advocacy group focused on utilities.

This year marks Wisconsin Citizens Utility Board’s 40th anniversary. Over the years, CUB’s survival has depended on staying true to its mission of consumer advocacy rather than environmental activism.

The two missions can sometimes be at odds. For example, CUB recently found itself taking a different position than environmental groups on proposals for high-voltage transmission lines and large solar farms. But with renewables becoming cheaper and myriad new solutions available to promote energy conservation today, CUB sees its consumer focus increasingly dovetailing with environmental and clean energy groups’ interests.

“All the stars are aligning for clean energy, with the utilities, renewable energy advocates, and now our governor all advocating for the same thing,” said CUB executive director Tom Content. He covered the state’s energy landscape for years as a reporter for the Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel before joining CUB.

“We’re a customer group not an environmental group, but we’re cognizant that whether it’s because of economic forces or reasons more linked to carbon emissions, more change is happening now in the energy mix than has happened in a long time,” he said. “Our part is how do you make that change in the most cost-effective way possible, especially in a state that just invested heavily in coal in the last 15 years.”

A long history

Citizens Utility Boards were born from a vision by consumer advocate Ralph Nader, who worked with organizers in Wisconsin to create the first such group in the country.

A 1979 state law created CUB and ordered Wisconsin utilities to include informational mailings from CUB in customers’ bills. Interested customers joined the organization in droves, paying membership dues of $3 to $5. At its height, CUB reportedly had about 100,000 members, and lots of impact.

In one early victory, CUB pushed the Public Service Commission to end utilities’ ability to automatically increase rates without public deliberation when fuel costs rose.

Kurt Runzler, CUB attorney and former acting executive director, noted that before state funding was instituted, the organization often received grants from foundations with environmental goals. Since then, however, it’s been especially important that CUB stick to its ratepayer advocacy mission, he said.

“There can be a tension between what’s considered quote-unquote green and what’s best for ratepayers in the long run,” Runzler said.

CUB’s entire future seemed uncertain in 2015 when the Republican-led Legislature voted to eliminate its grant of $300,000 a year. Republican Gov. Scott Walker used a line item veto to oppose the move, but couldn’t restore the money. CUB had to dig into its reserves to survive, Content said. In 2017 the funding was restored by a law supported by utilities and the governor.

“It was pretty unanimous that [funding] should be restored,” said Content, who was covering the issue as a journalist at the time.

In its recent budget bill the legislature considered CUB’s request to increase annual funding to $500,000. The change was supported by Democratic Gov. Tony Evers, Content said, but not by the Republican-controlled Joint Finance Committee, and the increase was not adopted. CUB is counting on memberships, which cost $35 a year for residential customers and $100 for small businesses, to grow.

Cost vs. environment

While some prominent clean energy groups have supported the proposed Cardinal-Hickory high-voltage transmission line that would bring wind and other power from Western states to Wisconsin, CUB has questioned whether it is necessary and cost-effective.

CUB has also raised concerns about two utilities’ plans to buy parts of two large proposed solar farms, Badger Hollow and Two Creeks. CUB initially argued that the utility WPS could buy into an under-construction natural gas plant to more cost-effectively provide additional energy.

And it questioned the structure wherein solar developers would build the farms before utilities bought them, avoiding a higher level of scrutiny that comes when utilities propose to build. CUB eventually supported the solar farm proposals after the commission reduced the ratepayer burden by $55 million by eliminating the utilities’ ability to collect additional funds for construction-cost overruns. The commission did not adopt CUB’s proposal for requirements to reduce the farms’ impact on adjacent landowners.

With several other massive new solar farms proposed in Wisconsin and more likely in the future, Content said, CUB must guard against utilities over-building or over-charging consumers for clean energy projects just as they might have done for coal plants in decades past.

“The utilities have this fiduciary responsibility to be watching out for their shareholders and their plans are contingent on always expanding, building more and more,” he said. “That’s where there needs to be somebody to say how much is too much” — whether it’s coal or solar.

The fate of aging coal plants is among CUB’s main focuses. We Energies and other Wisconsin utilities are seeking to retire coal plants and invest in utility scale solar, while still charging consumers for the coal plant construction costs. CUB supports cleaner energy, but doesn’t want consumers to be stuck paying for stranded assets, like $650 million We Energies plans to recoup for its closed 1,200-megawatt Pleasant Prairie coal plant, while also paying for new clean energy construction.

“If we have too much power and start shutting things down, ‘how’ is the question,” Content said. “Do you saddle customers with paying 100 cents on the dollar on the old stuff and on the new stuff also?”

Meanwhile CUB has been in lockstep with clean energy groups in other ongoing battles with utilities, including the standoff between We Energies and solar developer Eagle Point and the city of Milwaukee, over plans for third-party-owned installations on municipal buildings. Like clean energy and solar industry groups, CUB has supported the Eagle Point-Milwaukee project and opposed We Energies’ own plan to “rent-a-roof” from consumers for utility-owned solar.

Tyler Huebner, executive director for the renewable energy advocacy organization Renew Wisconsin, said environmental groups’ interests originally converged with CUB’s around energy efficiency, with CUB advocating supports for LED lights, smart meters and other measures that save consumers energy and money. Increasingly, Huebner added, clean energy can also be the cheapest option for new generation.

“Historically CUB with the long view in mind has been very supportive of energy efficiency programs that can help their customers reduce their bills today and reduce the total amount of electricity we need in the state,” Huebner said. “That scenario is where there’s a lot of overlap and common ground between clean energy advocates and CUB.

“Renewables a decade ago or more were more expensive and had to be justified on public policy reasons. Now those worlds are starting to converge, and as we talk about a tremendous expansion of renewable energy and reducing our reliance on coal, how do we do that in the most cost-effective way, looking at efficiency and customers owning their own generation and electric vehicles? There’s a really exciting confluence and CUB has a great role to play in helping the state understand how can we do it in a way that benefits customers as much as possible.”

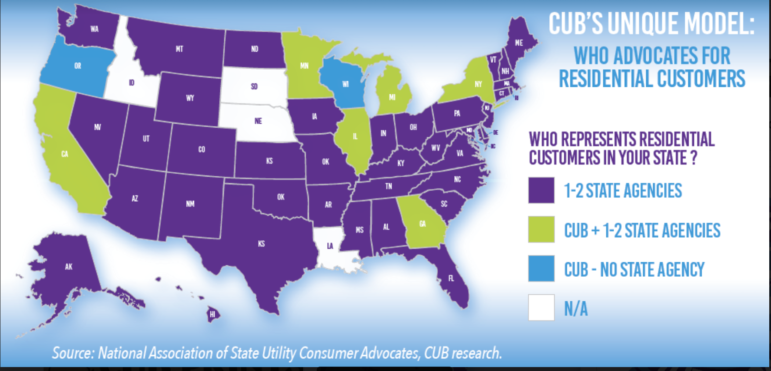

A map provided by the Wisconsin Citizens Utility Board shows how consumer advocacy for utility customers varies throughout the country.

‘David vs. Goliath’

Today, 44 states have an office within the state government, often in the Attorney General’s office, tasked with advocating for customers in utility proceedings. Four states have no official advocate for utility consumers at all, according to Content. Wisconsin and Oregon are the only states that have a private, independent organization but no government advocate.

States including Illinois, Michigan and Minnesota also have organizations called CUB. Illinois CUB was created by the state Legislature in 1983 with a $100,000 startup grant, and has been funded largely by members and foundation grants since. After the ruling that utilities can’t be forced to include CUB mailings in their bills, Illinois residents have received CUB materials in mailings from other state agencies. Minnesota CUB is likewise funded mostly by donations from members and foundations and a small amount of state funding.

“Wisconsin decided we didn’t want to create another extension of state government,” Content said. “In some ways even though we’ve been around the longest, we’re still in that David vs. Goliath situation because our budget is smaller than most CUBs, and smaller than a lot of state government” offices playing a similar role.

Nonetheless CUB has been successful, as backers see it, through its actions savings consumers $3.4 billion since 2006, and $84 million in 2018 alone, according to the group.

Michael Barnett, an energy efficiency and renewable energy consultant, became a CUB fan in recent years as he got engaged in the debate over third-party ownership of solar in We Energies’ territory.

“They’re the unsung heroes doing all this work in the background,” Barnett said. He added that when a utility request means a relatively small cost increase for individual customers, they may not get involved.

“No one person has much of a reason to advocate for themselves if it’s just one or two dollars a month, but that’s literally millions of dollars for utilities,” Barnett said. “So you really need to have an organization like CUB that can pool people together and advocate for them.”

CUB’s model has shifted in recent years, with the hiring of more in-house staff as opposed to seeking approval from the commission to fund expert witnesses for specific cases. Content and others inside and outside CUB say this allows them to take a more holistic and long-term view, rather than just reacting to utility proposals and litigating against them. Wisconsin CUB now has one in-house attorney and one in-house technical expert, along with legal and technical contractors. Content said the organization hopes to expand to hire at least one more technical analyst if the state Legislature approves the grant increase.

Having a larger staff will be even more important, Content said, given recent legislation for settling more rate cases through negotiations as opposed to drawn-out litigation.

Scott Smith, assistant vice president at Madison Gas and Electric, said the utility is glad for CUB’s move toward in-house staff.

“With professional staff we’re able to establish relationships about what we’re doing, why we’re doing it,” he said. “We can say, ‘Hey if we put this wind farm in, there will be a rate impact but it’s better than the alternative.’ … It’s not just about a rate case and then it ends; having those professional relationships really helps us work together toward common solutions. I don’t think we always agree on things, but if we don’t agree on things we understand the other side’s position.”

Courting millennials

Today CUB is trying to engage more younger members including through social media and events, like a 40th anniversary celebration and forum held at a Milwaukee brewery in April.

“I came from the print newspaper industry where you have subscribers and editors who worry every time there’s an obituary that you’re losing a subscriber,” Content said. “We’re holding onto a membership base that by and large is aging as well. That’s why we’re working to reach out to a new generation of folks, just as newspapers are doing with online subscriptions.”

CUB is holding a series of utility bill clinics throughout the year and participating in larger events like the Midwest Renewable Energy Association’s annual renewable energy fair in June in Custer, Wisconsin, which brings together clean energy aficionados from graying solar pioneers to ambitious young start-up entrepreneurs.

“If you’re someone interested in clean energy and reducing your carbon footprint, there is an appeal [for CUB] there,” Content said. “People often think of sustainability as the triple bottom line: environment, equity, economy. The environmental aspect is being fulfilled by others, and we’re making sure things are fair and making sure things are affordable as we make this transition to clean energy.”

This story was originally published by the Energy News Network.