“Close MSDF!” Protestors Declare

Those who suffered inside the county’s secure detention facility, call for its closing.

Sylvester Jackson, a former Milwaukee Secure Detention Facility (MSDF) inmate, pointed toward the facility, calling it an “illusion to the city.”

“They got those fake windows up there to make people think those are office buildings,” he explained. “Inside that shell, you can’t see nothing.”

Jackson, a middle-aged, African American man with a silver-trimmed beard, described his time inside the notorious facility as “hell.” He had gathered with several others for a monthly “Close MSDF” picket. Despite rain clouds overhead last week Thursday, they sought to raise awareness of the controversial facility, holding their monthly protest.

In 2017, Jackson told Urban Milwaukee, he was sent to the detention facility three separate times ranging from six days to one month. Like many other detainees inside the jail-like facility that looks from the outside like an office building, Jackson was accused of a probation violation.

The facility was conceived as a solution to over crowding at the Milwaukee County Jail. Over the years it has broadened the range of prisoners held within its walls. Mostly those who’ve fallen victim to what activists refer to as “crimeless revocations.” Things like testing positive for drugs, missing a meeting with your parole officer for any reason, or having a GPS device malfunction.

“It’s filled with people who are in there for no good reason,” says Close MSDF organizer Ben Turk. He says MSDF is part of “an inhumane system which cycles people back into incarceration.” And, as history has shown, not everyone who enters MSDF leaves alive. Such as 34-year-old Jeremy Cunningham, who suffered a fatal seizure inside the facility in 2011. Cunningham had turned himself into his probation officer after relapsing and using alcohol and narcotics. Although he wanted help, Cunningham was instead sent to MSDF.

In March of this year another man, 51-year-old William Leary, became the 17th person to die inside MSDF since it opened in 2001. Although investigations are still ongoing, reports indicate Leary left a note stating correctional officers weren’t helping him. He died on Sunday afternoon, March 17th, of a still undetermined cause. Shortly afterward, and days before Close MSDF’s March picket, unidentified persons threw paint at the facility’s sign. WISN 12 states it received an email from the alleged perpetrators with a picture of the act. The email stated the sign was defaced due to Leary’s death days earlier.

Close MSDF organizer Ben Turk called the defacing a “blurp we’re all moving past.” The unrelated act hasn’t affected Close MSDF’s work, nor has it attracted any obvious police attention to their protests.

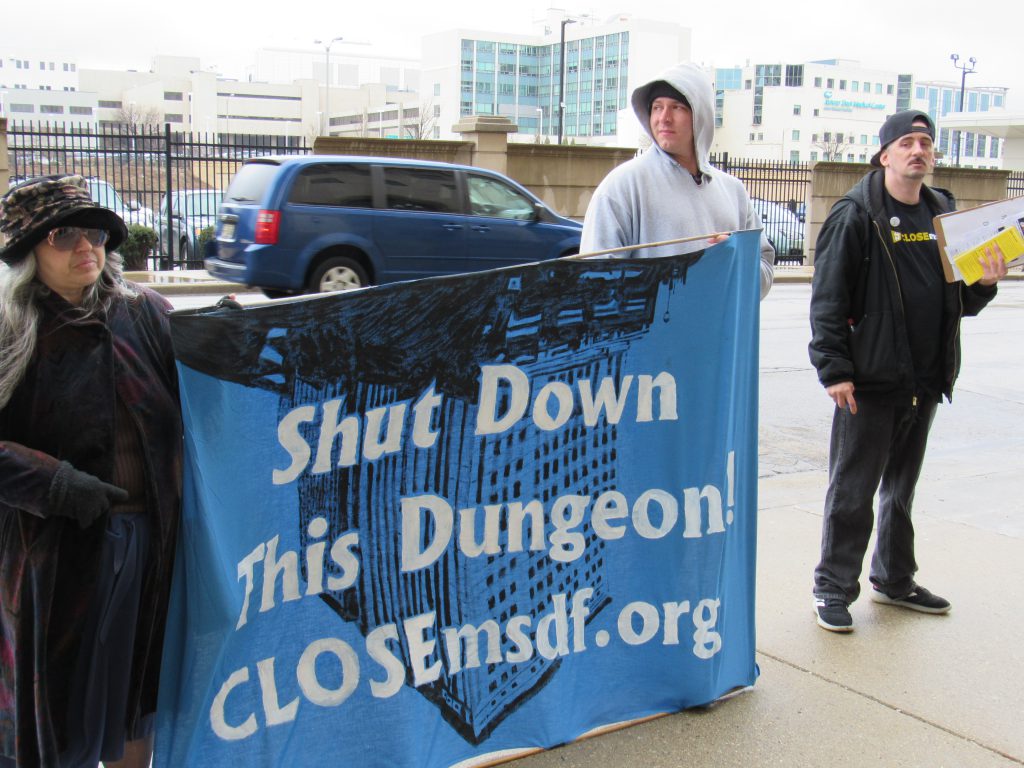

Jim Beadle, who was helping hold a large Close MSDF banner, feels that a few years ago, closing MSDF might have been considered a “radical idea.” The Philadelphia native and self-described “prison abolitionist” applauds the group for “making the idea of closing MSDF more mainstream.” After moving to Milwaukee three years ago, he joined the group for one reason. “MSDF is the most obvious symbol of the oppression that this city has gone through forever,” he told Urban Milwaukee.

On the other end of the same banner was a soft-spoken older woman, Babette Grunow. “I used to talk to a prisoner there,” she explained, “and could see that it was really hurting him.” She says because MSDF “looks like a corporate building,” it’s easily tolerated by residents. “I don’t think most people care,” she confessed.

Jackson says that during one of his stays he was made to sleep on the floor due to MSDF being overcrowded. Despite having a capacity of 1,040 people, MSDF averaged 1,077 people during 2017. “You have to sleep with two people,” says Jackson of sleeping on the floor. “So in the night people have to go to the bathroom. Your head gets splashed, your feet get splashed.” He says the food is poor, and he’d sometimes refuse it because “I couldn’t identify what I was eating.” After leaving the MSDF, Jackson said he noticed he’d lost a lot of weight.

The issues occurring inside the MSDF are common throughout the prison system. “Every prison I’ve been in I’ve seen people die,” says Jackson. But what makes MSDF unique is that the vast majority of its occupants were re-incarcerated without any new convictions. As many Close MSDF organizers point out, that cycle can result in the loss of jobs, rented homes, and other problems that make it difficult for ex-offenders to be rehabilitated.

This destabilizing effect has been noticed by politicians including Democratic Governor Tony Evers, and Rep. Evan Goyke (D-Milwaukee) Both have expressed interest in reforming or closing the facility. As it stands, the facility, with an annual budget of more than $39,000,000, continues detaining people at “$35 a head,” according to Jackson.

Meanwhile the Close MSDF pickets will continue. Scheduling for the May picket will appear on the Close MSDF Facebook page for those interested.

.If you think stories like this are important, become a member of Urban Milwaukee and help support real independent journalism. Plus you get some cool added benefits, all detailed here.