Why State’s Dairy Farms Face a Crisis

And why Gov. Evers should change the policies of his predecessor.

There is little doubt that many of Wisconsin’s dairy farms are in deep trouble.

The Journal Sentinel’s Rick Barrett has reported a series of articles with titles like Family farms decimated by Wisconsin’s dairy crisis, Amish dairy farmers at risk of losing their living and way of life as their buyer drops their milk, and Wisconsin dairy farmers barely hanging on as crisis deepens with no end in sight.

Concern about the future of Wisconsin’s dairy farms is not limited to the Journal Sentinel. Last month, the Washington Post published a column by Jim Goodman, an organic dairy farmer and activist from Wonewoc with the title Dairy farming is dying. After 40 years, I’m done.

These articles report that Wisconsin lost about 500 dairy herds in 2017 and is on track for about the same number in 2018. While Trump‘s battles with our trading partners have made the crisis worse, the underlying cause is more basic: the supply has outrun demand for milk and other dairy products.

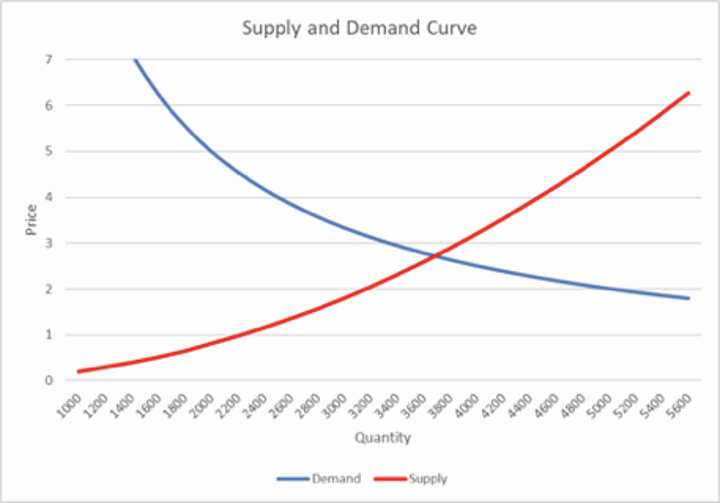

Early in every elementary microeconomics text is a graph like the one below. It is the supply-demand curve. The red line shows what happens to the supply of most products. As the price, shown on the vertical axis, goes up, so does the supply, shown on the horizontal axis. For example, farmers may add to their dairy herds to take advantage of high prices for milk.

Likewise, the blue line shows demand for a normal product. As price goes up, customers buy less of it and may switch to substitutes, such as juices.

In a market economy, equilibrium occurs where the two curves cross, at a price where supply equals demand.

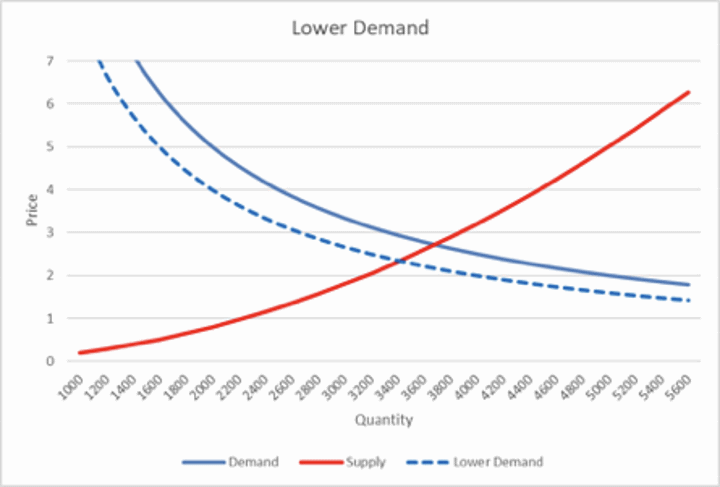

What happens if the supply curve changes so that suppliers are willing to deliver more supply at a given price? The dashed red line in the next graph shows the effect of increased supply. The price drops.

What could cause the supply curve to shift this way? One example comes from a current appeal to the federal 7th Circuit Court of Appeals, called Eli Lilly and Co. v. Arla Foods USA, Inc. A division of Lilly makes an artificial growth hormone that prolongs lactation of dairy cows, resulting in more milk production. In response to such products, Arla Foods, a Danish cheese company intent on expanding its US market, has run a series of ads stressing that its cheese was made from cows that weren’t fed any “weird stuff” including the growth hormone.

Concentrated animal feeding operations (“CAFO”) offer another way to push down the supply curve. The US Department of Agriculture defines a CAFO as an animal feeding operation in which animals are raised in confinement and that has more than 1,000 “animal units” confined for over 45 days a year. In Wisconsin, it appears that CAFOs are growing their market share as smaller farms give up.

The next chart shows the effect of a lower demand curve, shown as the blue dashed line. The expected result is both lower prices and lower quantities.

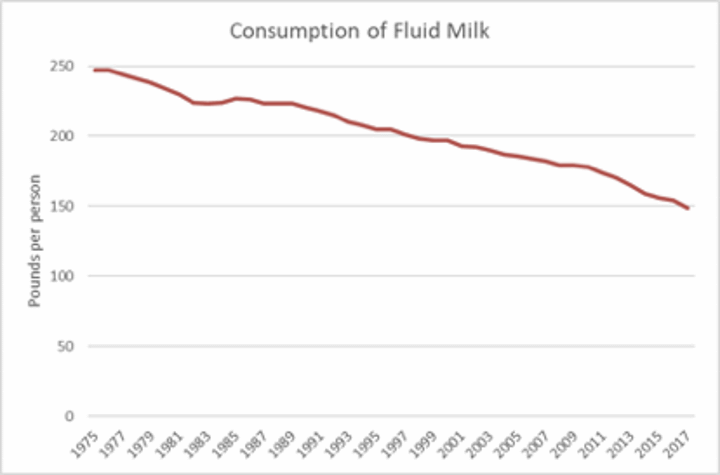

Over the years, per capita consumption of fluid milk, including whole, reduced fat, low fat, skim and flavored milk, and buttermilk and eggnog, has declined, as shown in the graph below, based on US Department of Agriculture data.

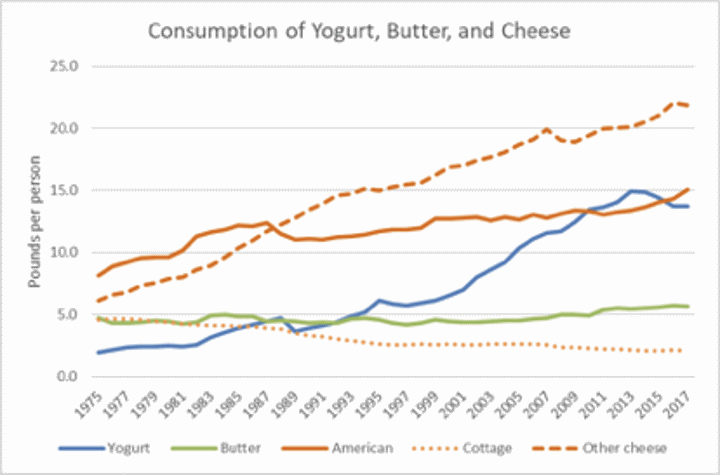

Some of the gap has been taken up by other milk products, particularly yogurt and “other” cheese, presumably everything but American cheese and cottage cheese. But none of these enjoyed growth sufficient to compensate for the decline in milk consumption.

Why are people consuming less milk? One factor is surely competition from other beverages including soft drinks and various juice products.

Another is that discussion of additives like growth hormones undercuts milk’s image as a pure product of nature. Thus, Lilly’s product may have given a double whammy to the dairy economy, by both increasing supply and decreasing demand. Even if the FDA concludes that milk from cows treated with growth hormones “is equally safe and healthy for human consumption as other milk,” such treatments are likely to make many consumers wary.

Another solution that has attracted support among some dairy farmers is some version of the Canadian system in which the government sets quotas on farms so that the supply equals projected demand, basically the New Deal model. The Canadian system seems to have worked well for that country’s family farms.

President Trump has taken to blaming the Canadian system for the American dairy crisis and demanding that it be upended. Canadian politicians may view this as a demand that they import the American farm crisis.

Any strategy to protect Wisconsin’s family dairy farms should be built around steps to counter the two causes of the crisis: declining demand and increasing supply. In his Washington Post column, Jim Goodman suggests one possible route:

But organic dairying has become a victim of its own success. It was profitable and thus fell victim to the “get big” model. Now, our business is dominated by large organic operations that are more factory than farm. It seems obvious that they simply cannot be following the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s strict organic production standards (like pasturing cattle), rules that we smaller farmers see as common sense.

Making sure that large producers strictly follow the rules could help reassure consumers (if they are) or reduce the surplus (if they are not).

Then there CAFOs, which have been blamed for polluting groundwater. They often also involve high-capacity wells. In addition to protecting the environment from such pollution, strict environmental standards would have an economic impact. By internalizing previously external costs for these companies, strict rules may discourage the growth of supply. Instead, the Walker administration bent over backwards to give them the needed permits.

In June 2018, then-governor Scott Walker appointed a task force to explore solutions to the dairy crisis, called Dairy Task Force 2.0 in recognition of an earlier task force from the 1980’s. From their early reports, it appears that the members adopted the view that the problem with Wisconsin dairies is that they are not sufficiently efficient. Thus they may end up making the crisis worse, as more efficiency means a bigger supply and still lower prices for dairy products.

I hope the new Wisconsin administration makes solving the dairy crisis a priority. There are several reasons why it should. One is that Wisconsin, including its urban dwellers, will be impoverished if the family dairy farms disappear from the countryside, especially if they are replaced by huge CAFOs.

Another is to start to heal the state’s growing hostility to Milwaukee from rural counties. It is notable that Jim Goodman’s Wonewoc is in Juneau County, one of the many rural Wisconsin counties whose turnout for Walker increased compared to four years ago.

Data Wonk

-

Life Expectancy in Wisconsin vs. Other States

Dec 10th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Dec 10th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

-

How Republicans Opened the Door To Redistricting

Nov 26th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Nov 26th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

-

The Connection Between Life Expectancy, Poverty and Partisanship

Nov 21st, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Nov 21st, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

It seems to me the main culprit is “CAFO”, from the November 2018 article “Wisconsin dairy farmers barely hanging on”…..

“As of Nov. 1, the dairy state had lost 660 cow herds from a year earlier, and the number of herds was down nearly 49 percent from 15 years ago. The number of dairy cows in Wisconsin has remained steady even as the number of farms has fallen. That’s because the remaining dairy operations are, in many cases, much bigger….”

Just another example of the corrupted “United States of Oligopoly”

Bruce’s analysis is spot-on. Former Governor Walker’s misguided campaign to dramatically increase Wisconsin’s milk production, which involved gutting the DNR’s regulation of CAFOs, preventing DNR enforcement of water and air pollution laws, and acrtual subsidization of infrastructure for some large CAFOs, has led to the inevitable results: a collapse in milk prices, loss of hundreds of small dairy farms, and widespread rural water pollution problems. Wisconsin has been open for only SOME businesses, at great cost to the state’s environment, economy, and residents.

I agree with he above. Additionally, If the Current Lack of Administration in Washington ever succeds in sending forth its “relief” to the dairy industry, I recommend that the just way, the sustainability reinforcing way, is to deliver the funds in reverse formula. The smaller the farm the bigger the cash benefit. If we are to have something left after the collapse we are bringing upon ourselves we need someone with the knowledge, skills and hands on experience of getting up at 4 am and hand milking those wonderful cows with names – the way it was done before our fossil fuel dependency. That will bring back the family farms AND the rural lifestyle that was a community. Yes, we will need a lot of them. What is the problem with that? Some might even be “in” the city!!! Did I hear someone say Urban Agriculture?