The Voyage of Donald Baumgartner

High seas adventure weathered perilous storms. Excerpt from book on Milwaukee businessman and philanthropist.

Donald Baumgartner has lived a storied life. Along with the standard labels “businessman” and “philanthropist,” add to the list short-order cook, machinist, art collector, opera aficionado (he cries during arias), film buff, race-car driver, boatman, and roles that are not easily categorized.

He has dined with Jane Fonda, shaken hands with Ronald Reagan in the White House Rose Garden, attended the Grammy Awards as sponsor of a production by Milwaukee’s Florentine Opera, and opened his East Side home to Playboy Magazine for a photo shoot.

Since turning over his manufacturing company, Paper Machinery Corporation, to his employees in 2016, Donald has donated mightily to Milwaukee arts groups with his wife, Donna. Their name will hang on the new Milwaukee Ballet center, now being built in the Third Ward.

Among his proudest feats was crossing the Atlantic on a pleasure yacht—and living to tell about it. Here is an account of that journey, excerpted from a new biography of Baumgartner.

The Crossing

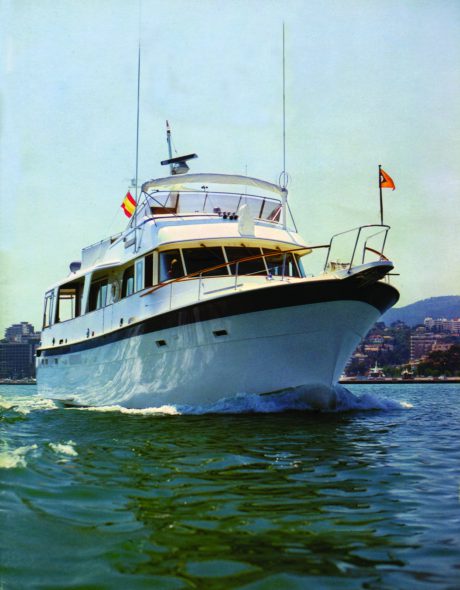

A year or so before Donald and Donna tied the knot, Donald’s father bought a fifty-eight-foot long-range cruiser made by Hatteras Yachts. Having owned dozens of boats, Bob “The Skipper” Baumgartner was looking for a way to get his pleasure craft Trenora (Sea Witch) across the Atlantic to southern Europe for future cruises.

The new Hatteras model had never been tested for a “blue water” ocean crossing. Could it make it safely and comfortably?

The idea for the crossing was hatched in 1978 at a Chicago steakhouse where Donald, Donna and Bob were having dinner. “My dad said he wanted to get the boat to the Mediterranean for the summer. He was going to ship it over by deck cargo, and it was going to cost him $60,000. I said, after perhaps one too many martinis, ‘Well, for Christ’s sakes. It’s a long-range cruiser. If it has the capability of crossing the ocean with fuel, why don’t you just sail it across?’ He said, ‘Don’t be ridiculous.’ And I said, ‘Well, hell, if you won’t, I will.’ That’s when the extra martini kicked in.”

Donald, at age forty-eight, he was nearing the half-century mark. Having just read a biography of Gen. Douglas MacArthur, he was pumped with bravado and not content to live in the shadow of his father, who had once ridden out a hurricane off the coast of Florida. So Donald took his midlife crisis and his girlfriend on the high seas for a high-stakes adventure.

The longest leg would be from Bermuda to the Azores Islands, 1,780 miles. Donna had stocked the yacht’s galley with meals prepared and packaged by a gourmet chef. The servings, such as beef Wellington, would be microwaved and paired with fine wines and champagne, leading one boating magazine to dub the cruise “the Champagne Crossing.”

Trenora left port from Bermuda on Monday, April 30, 1979. On board were Donald and Donna; Donald’s son, John; John’s girlfriend, Terri Hayes; and a young deckhand, Eric Lindboldt. The sky was blue and the weather was fair. The calm wouldn’t last long. Weather Routing, a radio broadcast service, had alerted them to a storm that was building over the Grand Banks, the massive underwater section of the North American Continental Shelf southeast of Newfoundland. A rich international fishing ground, the cold-water Labrador Current meets the warm–water Gulf Stream at the Banks, often spawning cyclonic storms in the North Atlantic.

The shortest distance across the Atlantic is not a straight line but an arc, called a Great Circle Route. Rather than following a constant heading, ship captains adjust their course periodically to stay on the arc. But, heeding the warning from Weather Routing, Trenora was forced to deviate from the Circle Route.

“The weatherman sent us farther south,” Donald says. “And so we couldn’t take the shortest route. We were way above the equator in the north latitudes, an area referred to by sailors as ‘the Roaring Forties.’ So, by going south, it increased the distance rather considerably, and we had to use up more fuel.”

Despite the threat of a storm, the crew of Trenora didn’t interrupt their Champagne Crossing. There were dolphins and whales to observe, delicious dinners to feast on, and late night disco dancing to Saturday Night Fever.

On Day Six en route to the Azores, things got more serious. The weather service advised Donald that the Grand Banks system was developing into a cyclonic storm—a potential hurricane—and moving their way. Donald ordered a lifeboat drill and the inspection of all life jackets as a precautionary measure. He also came up with a brilliant idea: flood the empty keel fuel tanks with seawater to provide more ballast. Thousands of pounds of diesel fuel had been drawn from the tanks in the course of the cruise from Bermuda. This gradually reduced the ballast in the very bottom of the yacht. Pumping water into the tanks replenished the ballast and helped prevent the boat from rolling.

“It was a very top-heavy boat,” says Donald, “and as we emptied the tanks, the boat kept getting higher and higher out of the water and rolling more and more. So I filled the tanks with seawater. As we used fuel, I put sea water in the empty fuel tanks to help keep the boat stable.” Still, the seas were unforgiving.

Pretty rough. Wind west on our stern. Boat tipping 20-25 degrees. . . . Starboard generator quit. Now on one generator. Can’t use air conditioning or water. . . . We’re all filthy.

—Trenora log entry, May 6, 1979.

While they veered away from the northern storm, another storm system was coming at them from the south. “We’re six or seven days at sea and we now have to make a decision,” says John Baumgartner, looking back. “Based on fuel consumption, you cross the point of no return. You no longer have enough fuel to turn around and go back to Bermuda. We now have to adjust our course and go for the Canary Islands, south off the western coast of Africa, or go for the Azores, off Portugal. We make the decision to continue our course to the Azores. We’re getting a rough ride. We’re no longer into a nice pleasure cruise.”

No radio contact. . . . Boat rolling to 40 degrees. Squall coming 20 knots behind us. Waves breaking over the bow. . . . Finally got radio contact to weatherman.

—Trenora log entry, May 9.

“This was not a boat that was meant to bear the force of a million gallons of water slamming into it with the might of a runaway freight train,” says Donald. “We knew we had bitten off a lot more than we could chew.”

Trenora was fifty miles from its destination, the town of Horta in the Azores, when they finally regained contact with a weatherman at Weather Routing. His report was not encouraging: “Grand Banks system still building. Serious depression from the south. Suggest you head directly for Horta and make the best of it.”

The entry to Horta was a nightmare, with the winds gusting at forty to fifty knots. “We were three miles from Horta,” says Donald, “and due to the wind and spray, we couldn’t even see the island with binoculars. I’ve never heard winds howl like that.”

As midnight approached, John heard Portuguese being spoken on the VHF radio. When he put out a call asking for assistance, the reply came back in English. The captain of a 300-foot inter-island ferry, the Ponta Delgada, was in the vicinity, and he offered to guide Trenora into Horta. But to get there, the boat would have to go around Faial Island and cut between the islands from the east.

“He held his position for us to come up on his stern and follow him into the port,” says John. “We could see his masthead lights and everything, we were so close. At this point we’re thinking, We’re there! But this is where we almost didn’t make it.”

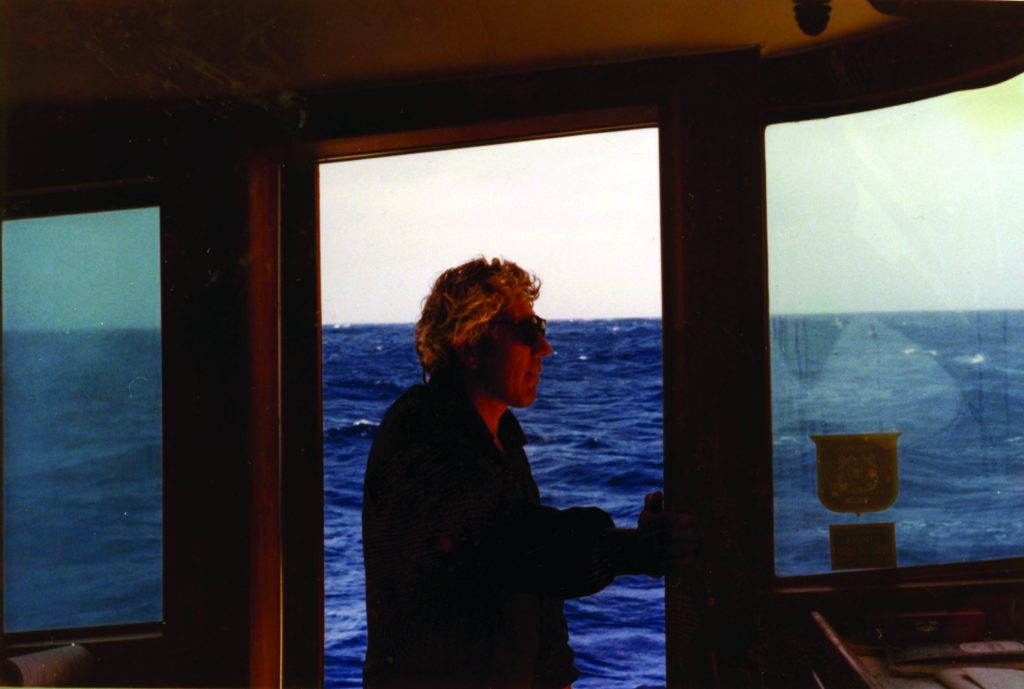

Funneled into the channel between the islands, the breakers exceeded twenty feet. “The wind was blowing now at seventy knots, and we were rolling up to forty degrees,” Donald says. “The bow of the boat was so far down in the swell that the propellers were out of the water just turning in the wind. I was at the helm and did all I could do to keep the boat from broaching—its side to the wind and sea.”

Donald and John kept their eyes fixed on the freighter’s lights. “He went up, up, up, up, up, and we’re in back of him,” Donald says. “Then, all of a sudden, it’s like he just disappeared, vanished over the top of the wave. Seconds later, we came up behind on the same wave he was on, and we surfed into the harbor totally out of control on a giant breaking wave in the middle of the night.”

The Hatteras LRC-58 traveled 3,818 nautical miles while underway for 460.8 hours at an average speed of just under eight knots.

“They called our boat a long-range cruiser but it wasn’t meant for a long-range crossing,” says Donald. “No, it’s strictly a pleasure yacht. It was not a boat that was built to do what we did. The Hatteras people were quite impressed. They put us on the cover of their magazine. We were the only Hatteras that had ever crossed the ocean.”

After passing through the Straits of Gibraltar, they docked in some of the coast’s most picturesque ports: Calpe, Savilla, and Cadiz in Spain; Antibes and Nice in France. “I remember going to San Tropez,” says Donna. “As luck would have it, they were just wrapping up the Miss Nude Riviera contest, and we were sort of the beneficiaries of that. Donald took off his trunks and went skipping down the beach.”

The Champagne Crossing was the cruise of a lifetime. The bumps, the bruises, the unrelenting storms and unforeseen diversions—all were more than the crew had bargained for, but counterbalanced by their display of vigor and nerve, and sense of sheer awe as they conquered the breadth of the turbulent Atlantic.

“It was more than a crossing, it was a passage for me,” Donald says. “To paraphrase the explorer Edmund Hillary: It’s not the mountain or the ocean we conquer, but ourselves.”

The voyage also sealed the future of Donald and Donna. “That’s when we knew we were going to get married,” says Donna. “After we survived it all, we felt we could survive anything, even marriage.”

Storm tested, cyclonic tough. Or, as Donald puts it: “It was one hell of a date.”

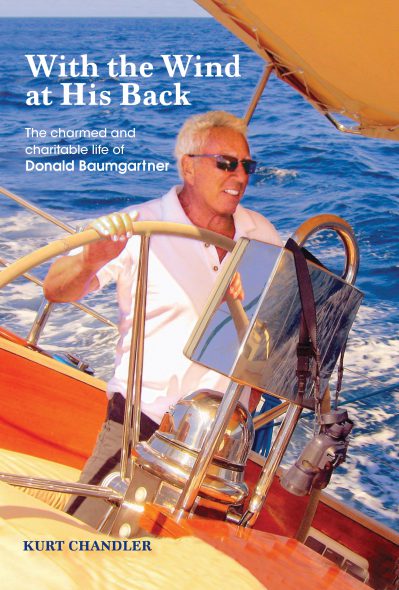

Kurt Chandler, a past editor of Milwaukee Magazine, is the author of “Shaving Lessons: A Memoir of Father and Son” and “Courtroom Avenger: The Challenges and Triumphs of Robert Habush.”

“With the Wind at His Back” is available at Amazon.com, SeattleBookCompany.com, and select bookstores. Chandler and Baumgartner will discuss the book on Oct. 22 at 7 p.m. at Boswell Book Company, 2559 N Downer Ave.