How Joe Zilber Changed Lindsay Heights

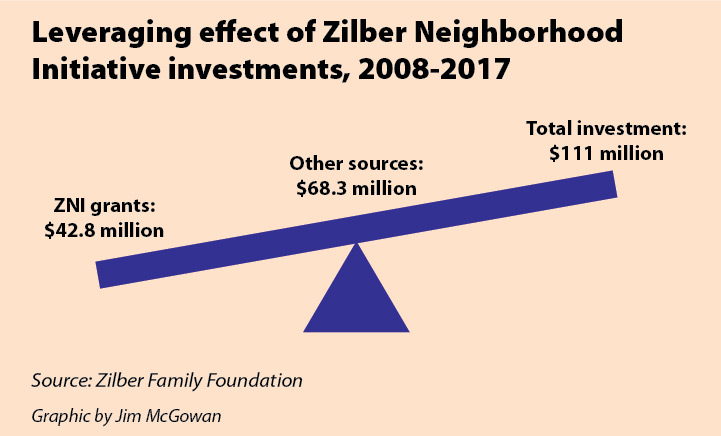

Zilber Initiative's funding leveraged $111 million investment in near North Side neighborhood.

Decade-long Zilber Neighborhood Initiative changes trajectory of Lindsay Heights. Photo courtesy of NNS.

When Lindsay Heights residents Sharon and Larry Adams collaborated with neighbors to found a community organization called Walnut Way Conservation Corp., one of their first projects was to plant 1,000 tulips.

It was the early 2000s and their ultimate mission was to reverse the effects of decades of disinvestment and deterioration. Sharon Adams dreamed of bringing back the beauty, safety and cohesion of the neighborhood she grew up in in the 1950s and ‘60s. But the immediate goal was to beautify the area and lift residents’ spirits.

Since then, Walnut Way has continued to spearhead beautification, gardening and environmental efforts as it fosters economic development. Its annual budget has grown to $1.2 million. Blue Skies Landscaping, a social enterprise it established in 2013, now brings in $450,000 to $500,000 in earned revenue, or about 40 percent of the nonprofit’s annual operating budget. It also employs 15 neighborhood residents.

Blue Skies is one of “two tremendous strongholds on our path toward true sustainability (that) are anchored by support from the Zilber Neighborhood Initiative,” said Walnut Way Executive Director Antonio Butts. The other is the Innovations and Wellness Commons at 1617 W. North Ave.

Blue Skies’ clients include the city, county, nonprofits such as St. Ann’s Intergenerational Center, Fondy Farmers Market and America’s Black Holocaust Museum, and businesses including Pete’s Fruit Market and the Griot Apartments.

Zilber chose “organizations that already had relationships with the people who lived and worked in the community,” to be the lead agencies in a resident-led community planning process, said Susan Lloyd, the foundation’s executive director from 2008 until July 5. ZNI supported that process, which resulted in Quality of Life Plans that have served as guides for each neighborhood’s revitalization work. Walnut Way is the lead agency in the 110-square-block Lindsay Heights neighborhood.

“The Quality of Life planning … positioned people around a common vision,” said Lloyd. “Even if the details change a little bit along the way … people have a sense of a collective effort to make change happen in a place.” She noted that the foundation was “driven completely by what was already in the Quality of Life Plans.”

The 10-year initiative ended this summer and Lindsay Heights leaders say most of the plan’s goals have been met or are on the way to completion.

The plan envisioned 13 catalytic projects that residents believed would strengthen the community’s infrastructure through new construction and renovation.

Sharon Adams, who founded Walnut Way with husband Larry and several neighbors to revitalize Lindsay Heights, stands across Fond du Lac Avenue from Johnsons Park. Photo by Andrea Waxman/NNS.

Sharon Adams, who stepped down as Walnut Way executive director in 2015, marveled at “the audacity of the community to say what was important to them in these brick and mortar projects. They went high,” she said.

Phase one of the Innovations and Wellness Commons (called the Center for Neighborhood innovation in the plan), was partially completed in October 2015 with the renovation of a vacant building that once housed a nightclub. The Juice Kitchen, Fondy Food Center administrative offices and a commercial kitchen operated by the Milwaukee Center for Independence rent space there. Outpost Natural Foods ran a pop-up grocery during the first year but now offers its space for community markets and gatherings.

Builders will break ground on new construction in October for phase two, a business and wellness hub anchored by the African American Chamber of Commerce of Wisconsin adjacent to the Commons, according to Butts. Seventy-five percent of the $4 million funding goal has been raised and “we expect (the building) to be completed by the second or third quarter of 2019,” he said.

The large-scale upgrade of Johnsons Park, which had become one of the most neglected play areas in the city according to a 2002 Public Policy Forum report, is an example of ZNI’s expertise in leveraging funds from other sources. Beginning in 2008, the Rotary Club of Milwaukee took the lead in raising about $2 million for the Johnsons Park Initiative that was started in 2005 by Preserve Our Parks, Center for Resilient Cities and other groups. The initiative’s goals were to re-grade the park to remove hidden areas that posed safety problems and install a new stage, lighting, bathrooms, picnic shelter, sports field surfaces, playground equipment and other amenities.

The project included early investments in Alice’s Garden, a two-acre urban farm where Venice Williams has offered garden plots and programming since 2004, and the Brown Street Academy schoolyard, where Rotary funded an outdoor nature classroom.

Sharon Adams, who founded Walnut Way with husband Larry and several neighbors to revitalize Lindsay Heights, stands across Fond du Lac Avenue from Johnsons Park. Photo by Andrea Waxman.

“One of the challenges for neighborhoods where there is a high percentage of poor people is that … it can isolate them from the knowledge, the relationships and the resources that they need to move forward,” Lloyd said. The Johnsons Park project is a great case … of building both the social relationships and doing the physical development. It’s consistent with Walnut Way’s approach from day one,” she said.

Rotary continues to be involved, Lloyd said. With Zilber and others, it has supported staffing and ongoing maintenance of the park, and built relationships with the neighbors. Rotary is committed to supporting the Johnsons Park Neighborhood Association and the newly formed Friends of Johnsons Park, said Mary McCormick, executive director of Rotary Club of Milwaukee

Lloyd noted that the early planning work that Walnut Way and the Social Development Commission did positioned Lindsay Heights to benefit from federal funds through the 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act.

“(It) was one of the few neighborhoods that had shovel-ready projects in the mix at the time that the resources needed to be spent,” Lloyd said. The projects were required to be completed in 18 months.

Other recent projects in Lindsay Heights include the redevelopment of the historic Walter Schmidt Tavern, 1848 W. Fond du Lac Ave., and the repaving of North Avenue.

Fix Development’s Juli Kaufmann and Jeremy Davis of Walnut Way developed the tavern project, which brought a new restaurant, the Tandem, and new office space to the neighborhood. Residents participated in the work and invested money in the project.

Co-developers Juli Kaufmann and Jeremy Davis pose in front of the Tandem restaurant in the historic tavern building they redeveloped. Photo by Allison Dikanovic/NNS.

Improvements to the North Avenue streetscape were initiated by Walnut Way as part of its beautification and general clean-up efforts, said Gina Stilp, who took over as the Zilber Family Foundation executive director in July.

Walnut Way did a great job developing relationships with the city and its Environmental Collaboration Office and working as a partner with Blue Skies Landscaping and the North Avenue Business Improvement District to install plants and planters and beautify vacant lots, business facades and street, Stilp said.

“The revitalization of our commercial corridors and the appetite for investment to be had in this area is obviously significantly trending upward,” noted Butts. “Over the last 10 years we’ve probably had more than $80 million of commercial development,” he said, adding that there will probably be an equal amount or more in the next 10 years. “The built environment is being transformed.”

Core values were integrated into the work, Sharon Adams said. “It wasn’t just the projects — and they were big and bold — it was the values: caring about each other, being good neighbors, sharing, believing that there is abundance.”

Lloyd said that Adams made a concerted effort to build relationships within the neighborhood and also bring relationships into the community. Adams understood that building an infrastructure of organizations — Neu-Life, the BID, Walnut Way, Fondy Market, the Lindsay Heights Neighborhood Health Alliance — would make the neighborhood resilient, she said.

Lloyd added, “At the end of the day, everybody wants the same things: safe streets, access to jobs, decent housing, good schools, Saturday morning shopping. In truth, they want what you want, what I want.”

Like a family

Will Walker, 49, has lived on the 2200 block of North 17th Street on and off for 46 years. He was an infant when his parents bought their house in 1972.

Before he graduated from high school in 1987, the residents on his block were predominantly families, Walker said, noting that he still has neighborhood friendships that started in the ‘70s.

“It was more a community up until the early ‘90s,” Walker said. But when family-supporting employment, such as his father’s foundry job, moved to the suburbs, many families that Walker grew up with left. Some of them rented their properties out “and that changed the whole landscape of the community.” Drugs took over, he said.

Walker moved back in 2007 when his mother invited him back to the family home, where he still resides with a brother and sister.

Walnut Way has fostered unity, camaraderie, fellowship and family, Walker said. It started helping young people get jobs and residents grow their own food, increasing self-sufficiency and healthy eating. And it promoted landscaping improvements that have renewed residents’ pride in their homes.

“My mother passed away in April and she had already had a garden … but when Walnut Way started, they gave her flowers and seeds, and I saw a spark in her,” Walker said.

The changes “instilled that whole vibe from when I was younger … It was like a total 180 (degree turn) from what it was in the ‘90s and 2000s and (the community) became like family again,” he said.

A remaining challenge, Walker said, is finding funds to maintain or upgrade his house. With his brother on disability and health issues of his own, those costs are beyond the family’s means. He would like to see the return of a program where volunteers assist residents with repairs, he said. Even low interest loans would help.

“In the past 10 years I’ve seen that we, as a whole, look out for each other and I know that starts with Walnut Way … letting the youth and the adults know that we are in this together.” The changes have been great for the community, he said.

Fear of displacement

Sandra Campbell, 64, also grew up in Lindsay Heights. She lived in her parents’ house on Garfield Avenue until the family moved to the 2200 block of North 16th Street, where her sister still lives. Her father and mother earned a middle-class living as a bricklayer and a postal service employee, respectively.

Campbell remembers a racially mixed neighborhood with healthy commercial activity on North Avenue. Ticking off the names of businesses she remembers from the ‘60s and 70s, she lamented the decline of the ‘80s and ‘90s.

Across 16th Street there was a pharmacy where a corner store now does a brisk trade in liquor. Across North Avenue was Powell’s Gift Shop, where the owners lived upstairs, Campbell said.

She moved away to be closer to a school where she worked as a paraprofessional. After a job change, a layoff and the acquisition of degrees in computer tech and security, Campbell moved back to live closer to her sister. She built a house on 17th Street, just south of Walnut Street, in 2007.

Campbell meets monthly with neighbors at the House of Peace to fight the displacement they fear will come in the wake of neighborhood improvements and downtown development.

Unlike her sister, who embraces the changes in the neighborhood and isn’t too worried about gentrification, Campbell is concerned.

About two years ago, she said, her property taxes started to rise significantly and then the Bucks built a new arena, the Fiserv Forum. Campbell believes the Bucks owners and others developing entertainment venues in the area fear that communities of color will scare patrons away and will work to displace people like herself and her neighbors.

Noting the displacement of long-time African-American residents in the Brewers Hill and Riverwest neighborhoods nearby and similar patterns in cities across the country, Campbell said she fears being pushed out of her neighborhood.

Antonio Butts grew up in Lindsay Heights and has deep roots in the community. After serving on the Walnut Way board for two years, he became executive director in July 2017. Photo by Andrea Waxman/NNS.

She said if she had foreseen the growth happening around her, she would not have built there. When asked about the likelihood that community efforts could stop people from being pushed out, she replied, “When have they stopped it? They didn’t stop it in New York. They didn’t stop it in Boston. They didn’t stop it in Chicago.”

Campbell would like to see current homeowners be able to stay where they are. “Let the people buy the (vacant lots) and build their homes. We can have a mixed neighborhood.

“I went to St. Boniface Church with Father Groppi. I went to mixed schools. We didn’t have all this separation until (white residents) decided that they wanted to do what we call “the great white flight.”

She said she has invested too much in her home to lose it. “The fight is on and I will keep going to the meetings,” she said.

Community leaders are well aware of the concerns Campbell voiced. Butts, who took over as Walnut Way executive director in July 2017, said it’s important for residents to have a stake in the revitalization of the neighborhood, “whether that be a (sweat) equity stake or some form of capital stake” and not be displaced.

Also important, Butts said, is making sure that residents have a role in the changes that are taking place, “and that the history, the legacy, the identity that exists in the community is honored in a way that has a respect for the past.

“Not only is the built environment worth investing in, the people who live in this community are worth investing in too.”

This story was originally published by Milwaukee Neighborhood News Service, where you can find other stories reporting on eighteen city neighborhoods in Milwaukee.