Could Foxconn Increase Downstream Flooding?

Illinois officials fear Foxconn development will worsen Des Plaines River flooding.

The Des Plaines River saw record flooding in 2013, including in the community of Gurnee. Photo from Lake County, Illinois (CC BY 2.0)

Flooding along the Des Plaines River in northeastern Illinois in the summer of 2017 damaged more than 6,000 buildings and prompted disaster declarations across three of the state’s counties. These floods broke records previously set in 2013, when the Des Plaines and other rivers around Chicago swelled with torrential rains. In June 2018, the Des Plaines flooded yet again, as did the Fox River to the west.

The Des Plaines begins at the southern edge of Racine County and, after a pair of bends in Kenosha County, flows south, then slightly southeast, for 133 miles through Chicago’s suburbs until it meets the Kankakee River to form the Illinois River, which flows westward into the Mississippi. Just like watersheds around Wisconsin, the Des Plaines watershed has experienced heightened flooding in recent years, and could be in for a lot more, as climate change increases projected levels of precipitation in the Midwest and the likelihood of extreme rainfall events.

Local and state officials in Illinois are beginning to worry about another force that could direct more water into the Des Plaines: The large campus Taiwan-based electronics manufacturer Foxconn is building in the Racine County village of Mount Pleasant. In fact, without adequate countermeasures, any future development in either southeastern Wisconsin and northeastern Illinois — which are populous and extensively developed areas already — could make these areas more vulnerable to flooding.

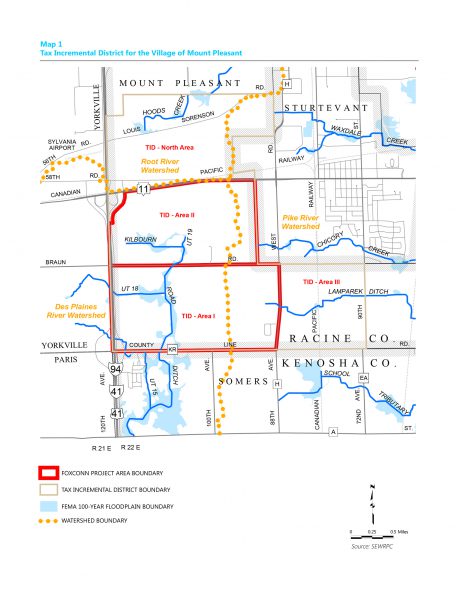

Much of the Foxconn campus footprint is in an area where water drains to Lake Michigan via the Root and Pike rivers. But the southwestern portion of the development is located in the Des Plaines River watershed, which means that rain and snowmelt in that area will drain via ditches, creeks and streams into the Des Plaines, or otherwise seep into the surrounding groundwater supply. Much of that land is used for agricultural or rural residential purposes, and will get covered with asphalt and rooftops.

In other words, just like any kind of large development project, Foxconn will transform ground that’s permeable to water — able to retain it in wetlands or draw it into the groundwater supply — into impervious surfaces from which rainfall and snowmelt tends to run off into surface water bodies, often flowing through storm sewers along the way.

In a heavy rain, water falling on rooftops or pavement will flood nearby lakes and rivers much more readily, because it doesn’t have anywhere else to go unless the local storm sewer system can keep up with the torrent. In turn, those sewers eventually have to drain somewhere.

Municipal and county officials in Illinois’ Lake County, which is just across from Kenosha County along Wisconsin’s southern border, have raised concerns that the Foxconn development will mean more flooding downstream for their communities. The Lake County Board passed a resolution in June opposing the loosened environmental standards that Wisconsin and federal officials have applied for Foxconn.

“If you fill in 26 acres of wetlands, there is going to be a downstream impact,” said Aaron Lawlor, chair of the Lake County Board.

Businesses in the Foxconn development zone can fill in wetlands without prior approval from the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources and build without giving the state and the public a chance to review an environmental impact statement, thanks to provisions the state Legislature ensconced in law by passing an incentives package (2017 Act 58). This change in Wisconsin’s policy prompted the Lake County Stormwater Management Commission to pass a resolution of its own, also in June, urging stricter environmental oversight of the project.

These action followed the Illinois State Senate, which on May 31 adopted a resolution raising concerns over the project’s potential downstream flooding impacts and its plans to draw water from Lake Michigan.

Both of Illinois’ U.S. Senators — Dick Durbin and Tammy Duckworth, both Democrats — and U.S. Rep. Brad Schneider, D-Deerfield, called in June for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to intervene and address the project’s role in flooding in the Des Plaines River watershed. However, the Corps declared in January that it does not believe it has jurisdiction over the project.

The Des Plaines River flows south from Racine County and through the Chicago suburbs. Photo by Brian Plunkett (CC BY 2.0)

None of the resolutions or other rumblings do anything legally binding. But Illinois Attorney General Lisa Madigan joined with the city of Chicago on August 2 to sue the Environmental Protection Agency for its decision, announced in May, to relax smog enforcement across several counties in Indiana, Illinois and Wisconsin, including Racine County. (Madigan had been talking about a lawsuit since May, but did not actually file one until August.) If federal courts allow the EPA’s policy to stand, this decision will make it easier and cheaper for Foxconn to comply with environmental regulations. Madigan has also voiced concerns about Foxconn’s potential impact on flooding in Illinois, and about the quality of the wastewater its factory will be discharging, via the Racine Water Utility, into Lake Michigan. She has yet to take any formal legal action on that latter point.

Of chief concern to Illinois officials is the impact of Foxconn potentially filling in 26 acres of wetlands throughout its construction site. The project currently plans to fill in 13.7 acres of wetlands in the Des Plaines River watershed, said DNR spokesperson Jim Dick.

“There is a large concern because of the record flooding we had last year, and we had more flooding in June this year,” said Mike Warner, director of the Lake County Stormwater Commission. “We were at flood stage two years in a row. There’s hundreds of homes that are in the floodplain….so there’s a very heightened concern that new impervious surfaces are just going to bring more water to us.”

Wetlands provide a natural barrier against flooding, retaining water and slowing its movement across the landscape. The various physical and chemical processes that take place as water slowly moves through a wetland, and eventually into the groundwater supply or a surface water body, can also improve its quality.

Foxconn must mitigate the wetlands it fills in by creating two acres of artificial wetlands to every acre it destroys. This requirement is perhaps the only sense in which the state law passed to entice the company sets stricter environmental requirements — under state law, businesses otherwise have to mitigate at 1.2 acres per filled-in acre. To this end, Foxconn has paid $2,037,020 into the DNR’s Wisconsin Wetland Conservation Trust program, Dick said.

Tomorrow’s development, yesterday’s rains

The Foxconn project will impact local watersheds within both the Great Lakes Basin and Mississippi River Basin. Map from the Southeastern Wisconsin Regional Planning Commission.

The Southeastern Wisconsin Regional Planning Commission, which covers seven counties in the Milwaukee metro region, released a study in June concluding that the Foxconn project shouldn’t create new flooding problems, pending two actions. One, Mount Pleasant would need to continue to follow its existing standards when building new stormwater infrastructure around the Foxconn development. Two, some stormwater retention basins planned for the site would in fact need to be built.

The Commission’s study of the Foxconn site’s impact on stormwater uses data on local precipitation gathered between 1940 and 1994. It’s a long-range, empirical dataset consistent with a Federal Emergency Management Agency study that mapped out floodplains in the area. But that date range means the study doesn’t account for potential increases in rainfall and the impacts of extreme rainfall events. Laura Herrick, the Commission’s chief environmental engineer, argued that considering such projections wouldn’t be possible.

Climatologists have developed models that project how much precipitation might increase, but different models make different calculations about just how much and where it could fall. While these models generally agree that weather will get wetter for the upper Midwest, Herrick said that none of them provide data that’s localized enough to gauge future rainfall impacts on the 1.5 square mile area of the Foxconn site.

“Of course, there’s going to be more runoff volume — that’s always true — but as far as peak flows coming off the site, they’re not going to make flooding worse downstream,” Herrick said.

The Southeastern Wisconsin Regional Planning Commission study also assumes that Foxconn will leave intact a significant amount of wetland and forested area at the Mount Pleasant site, and won’t fill in any wetlands in FEMA-designated 100-year floodplains, Herrick explained.

Lake County official Mike Warner said in late July that he had begun the process of reviewing the Commission’s study, and had asked for more details on the computer modeling the study uses to project the amount of precipitation that will fall around the Foxconn site. He hopes to release some additional findings by some point in August.

Meanwhile, Jim Dick said that DNR staff, along with staff from the Commission, have fielded questions about stormwater from the office of Illinois Attorney General Lisa Madigan, but have not heard from officials in Lake County.

Where to make up for it?

Foxconn’s construction site in Wisconsin is partially within the Des Plaines River watershed. Map by Kmusser (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Another factor at play is where and when Foxconn’s wetland remediation actually takes place. Even though Wisconsin law requires the company to replace twice the acreage of wetlands it fills in, the remediation won’t necessarily replace the particular hydrologic functions of the specific wetlands that are lost. Depending on its location and specific characteristics, one wetland may well have very different downstream effects from another.

For the purposes of figuring out where new wetlands should go, the Wisconsin DNR’s Wetland Conservation Trust divides the state up into 12 “service areas.” Each one effectively aligns with a watershed within either the Great Lakes or Mississippi River basins — for example, the Rock River and Lower Wisconsin River service areas in the former, and the Lake Superior service areas in the latter. If someone participating in the program fills wetlands in one of these service, the corresponding artificial wetlands meant as mitigation are supposed to end up in the same service area.

Developers don’t coordinate this planning directly; they pay into the program, and the DNR, which administers it, puts out requests for proposals for wetlands mitigation projects. Private contractors then bid for the funds by proposing the construction of artificial wetlands at specific sites within a service area. From the date a developer pays into the Trust, the DNR aims to get the mitigation work done within three years, though sometimes it can take longer, said Josh Brown, the program’s administrator.

Each of the wetland mitigation program’s service areas can be further divided into distinct smaller watersheds within those larger watersheds. (Environmental regulators have a system called the Hydrologic Unit code that divides watersheds into progressively smaller and smaller portions.) The Upper Illinois service area — the part of the Illinois River basin that reaches up into Kenosha, Racine, Walworth and Waukesha counties — contains a Fox River portion and a Des Plaines River portion.

Another Illinois River tributary, the Fox River, also flows south from Wisconsin into northeastern Illinois. Map by Fay2 (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Both the Fox and the Des Plaines drain into the Illinois, which is why they’re grouped together as part of the latter’s watershed unit. Even so, each river charts its own distinct courses and face their own issues with flooding along the way. A bunch of new development within that Upper Illinois service area could well impact the Fox and Des Plaines rivers very differently. If a developer fills in wetlands in the Des Plaines watershed but the corresponding mitigation work takes place within the Fox watershed, that might not be much help to communities downstream on the Des Plaines.

Lake County Board chair Aaron Lawlor contends that if any wetland remediation meant to make up for Foxconn development in the Des Plaines watershed isn’t located within the watershed, it won’t matter. He doesn’t entirely oppose the project — he credits Foxconn, for instance, with pledging to use water-recycling technology to limit its withdrawals of Lake Michigan — but wants to know more details about how the company will compensate for its impact on wetlands.

“We need to know specifically where it’s going to go,” Lawlor said.

A DNR guide to the Wetland Conservation Trust program says that participants should “strive” to act on the basis of these smaller watersheds. It does not create a hard-and-fast rule, though; the only firm requirement is that mitigation projects be within the same (and more broadly defined) service area as the corresponding filled wetlands, DNR spokesperson Jim Dick said.

Brown said that the Trust’s use of the 12 service areas reflect a “watershed approach.” When considering proposals, the DNR will weigh not just how to make up for the impact of one specific development, but also ask more specific questions what the best approach might be to address the aggregate impacts of recent developments and historic wetlands loss across a whole service area.

“I’d say if everything else was equal, two projects were completely the same and one was closer to the impacts, then we could give preference, but wouldn’t have to to give preference to that project,” Brown said.

While Brown said he hadn’t specifically heard about the concerns of officials in Illinois, that state’s residents will in theory be able to weigh in on the mitigation process. Mitigation projects the Trust pays for require approval from the Army Corps of Engineers, and the Corps’ approval process includes a public-comment mechanism.

In an area as rapidly developing (and already extensively developed) as southeastern Wisconsin, it can be difficult to weigh all the impacts of lost wetlands, or to even find open space where it would be appropriate to construct new artificial wetlands, Brown admits.

“Everything from land prices to land ownership to [whether] we’re not able to hydrologically impact adjacent lands without permission … all those are concerns or just issues we have to look out for,” he said.

In other words, the DNR’s process for having new wetlands created may take Foxconn’s impact into account, but that won’t necessarily be the only factor at work, and mitigation likely won’t happen as quickly as the construction itself.

Downstream From Foxconn, Anxiety Mounts Over Floods was originally published on WisContext which produced the article in a partnership between Wisconsin Public Radio, Wisconsin Public Television and Cooperative Extension.

More about the Foxconn Facility

- Foxconn Acquires 20 More Acres in Mount Pleasant, But For What? - Joe Schulz - Jan 7th, 2025

- Murphy’s Law: What Are Foxconn’s Employees Doing? - Bruce Murphy - Dec 17th, 2024

- With 1,114 Employees, Foxconn Earns $9 Million in Tax Credits - Joe Schulz - Dec 13th, 2024

- Mount Pleasant, Racine in Legal Battle Over Water After Foxconn Failure - Evan Casey - Sep 18th, 2024

- Biden Hails ‘Transformative’ Microsoft Project in Mount Pleasant - Sophie Bolich - May 8th, 2024

- Microsoft’s Wisconsin Data Center Now A $3.3 Billion Project - Jeramey Jannene - May 8th, 2024

- We Energies Will Spend $335 Million on Microsoft Development - Evan Casey - Mar 6th, 2024

- Foxconn Will Get State Subsidy For 2022 - Joe Schulz - Dec 11th, 2023

- Mount Pleasant Approves Microsoft Deal on Foxconn Land - Evan Casey - Nov 28th, 2023

- Mount Pleasant Deal With Microsoft Has No Public Subsidies - Evan Casey - Nov 14th, 2023

Read more about Foxconn Facility here