A Federal Jobs Guarantee?

NY Senator Gillibrand is pushing idea. Polls show people favor it.

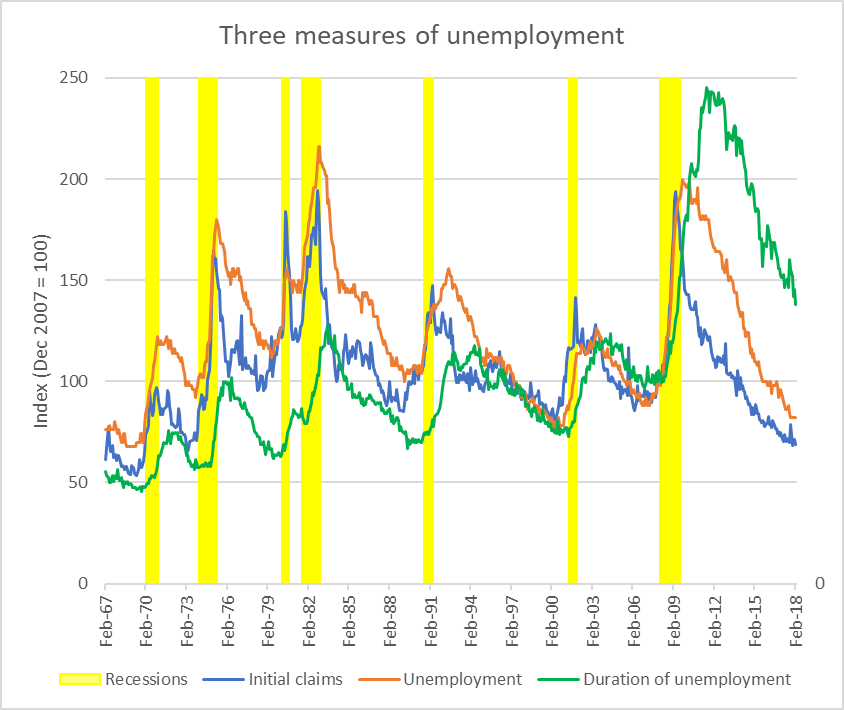

Recessions are marked by three employment statistics. Facing declining revenues, employers lay off employees, leading to a spike in the first measure, initial claims for unemployment benefits.

This leads to a growth in the second statistic, the unemployment rate. Even after initial claims level off and start to decline, the rate of unemployment continues to grow, so long as people lose jobs faster than they find them.

The third statistic, the average duration of unemployment, lags behind the other two. As the job market regains strength unemployed people with the right skills and in hot job markets are likely to be snatched up first. As the chart below shows, this sequence of events is common to the last seven recessions.

(This and the next chart are based on U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics data, downloaded from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis’s FRED web site. To show all three series on the same scale, I converted them to indices with a value of 100 in December 2007.)

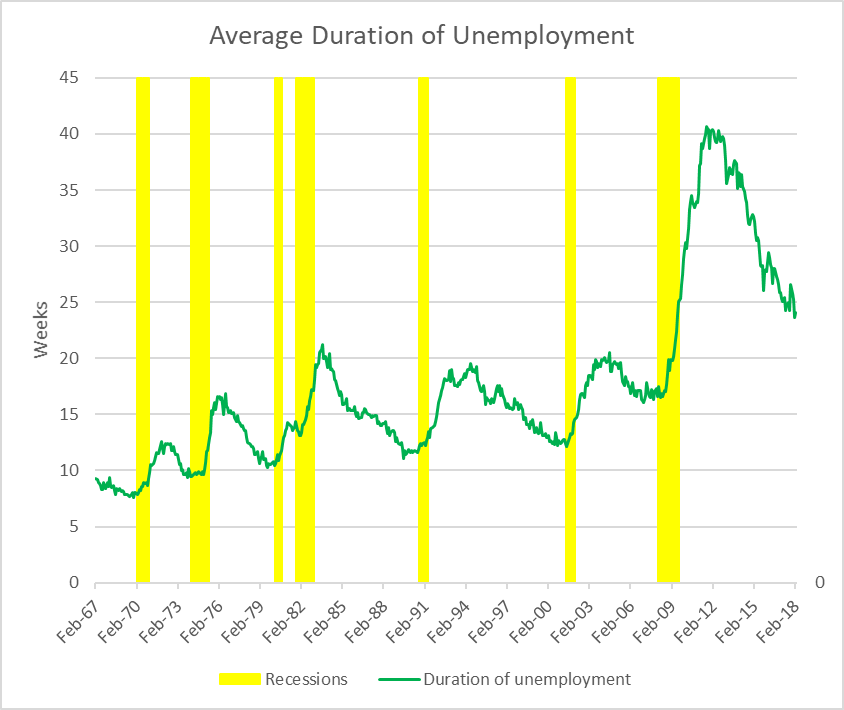

Despite following the common pattern, the 2008 recession differs from earlier ones, both then and in its lingering effects to this day. As the next chart shows, the average duration of unemployment peaked at 40 weeks, double that of the worst previous post-war recession, in 1982. Even today, after eight years of recovery, the average duration of unemployment exceeds the peak of any previous recession.

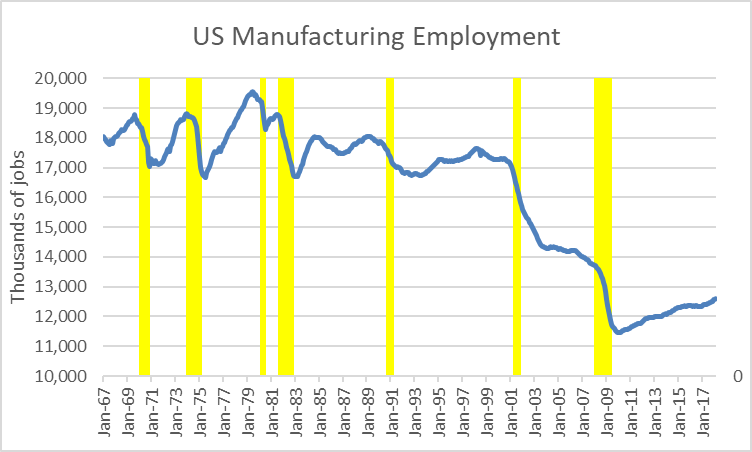

With the start of the new century, something changed. Before, if manufacturing jobs disappeared at one firm, another was waiting to pick up the slack. In Milwaukee in 1982, when manufacturers like Schlitz and Allis Chalmers closed their doors, others such as Tower Automotive needed workers with much the same skill sets.

As the next chart shows, the precipitous drop in US manufacturing jobs actually started half a decade before the Great Recession. By the time the recovery started, manufacturing jobs had declined from about 17 million to 11.5 million.

Attempts to halt these changes are often useless unless very well thought out. The George W. Bush administration attempted to staunch the loss of American steel production by putting tariffs on imported steel. One problem is that there are far more firms that use steel than make steel. Thus, Wisconsin manufacturers of, say, small engines found higher material costs while their foreign competitors were able to import foreign steel in the form of engines duty-free. Perhaps not entirely coincidentally, the big decline in American manufacturing jobs occurred during the Bush administration. It is clear that the present administration learned nothing from this experience.

Over the long run, this ability to change in response to technology or global competition is one of the great strengths of a free market. But these changes can be very rough on the people involved. It is estimated that 3.5 million Americans drive trucks. What happens to their jobs if research to create autonomous vehicles is successful?

While this idea may seem radical, it is not new. In 1968, a New York Times article reported that “a majority of Americans opposes a guaranteed annual income that would provide each family with a minimum income of $3,200 a year [about $23,000 today], according to the Gallup Poll. But they overwhelmingly support a plan that would guarantee each family enough work to provide this amount of money.”

More recent polls also show substantial support for a guaranteed job proposal. A YouGov 2014 survey found 47 percent of respondents either “strongly” or “somewhat” favored guaranteed jobs, compared to 41 percent opposed.

A recent poll by Civis Analytics asked whether voters would be for or against a bill to guarantee a job to every American adult, to be paid for by a 5 percent income tax increase on those making over $200,000 per year.

Fifty two percent supported this proposal, with 29 percent opposed, for a net difference of 23 percent in favor. An overwhelming portion of Clinton voters, a net of 43 percent, favored it. Although a majority of Trump voters opposed the proposal, the net difference was only minus 18 percent. Most voters switching from Obama to Trump supported the proposal (net of 29 percent), suggesting this might help bring some back to the Democrats.

In endorsing a jobs guarantee, New York Senator Kirsten Gillibrand said, “Guaranteed jobs programs, creating floors for wages and benefits, and expanding the right to collectively bargain are exactly the type of roles that government must take to shift power back to workers and our communities … Corporate interests have controlled the agenda in Washington for decades so we can’t tinker at the margins and expect to rebuild the middle class and stamp out inequality. We need to get back to an economy that rewards workers, not just shareholder value and CEO pay.”

While a federal jobs guarantee appears to be good politics, is it good policy? One strength is that it would kick in when most needed, as the nation enters a recession, when states, cities, and private firms cut back because of declining revenues. It would act to counteract trends concentrating a larger and larger share of wealth in the hands of fewer people, primarily benefitting those left behind by changes in the economy, such as minorities in inner-city Milwaukee and other cities, people living in coal-mining regions, or residents of rural areas and small towns.

If Gillibrand runs for president in the Democratic primary, we might see much more discussion of this proposal.

Data Wonk

-

Life Expectancy in Wisconsin vs. Other States

Dec 10th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Dec 10th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

-

How Republicans Opened the Door To Redistricting

Nov 26th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Nov 26th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

-

The Connection Between Life Expectancy, Poverty and Partisanship

Nov 21st, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Nov 21st, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Bruce T., many thanks.

Republicans haven’t figured out that a pool of employable workers in a job guarantee program limit union leverage.

Employers don’t have to hire, but people have to eat.

I give her a lot of credit for identifying the funding source for this idea right up front.

I also think the idea of the ‘Universal Basic Income’ is going to be discussed more and more… and I understand why. If automation does end up taking 10-15% off our employment base just to start, in 10-15 years, for customer-service and driving/trucking positions (just as an example, I’m sure there will be many more), what do you do as a nation?

@WashCoRepub, agreed and well said! UBI and/or job guarantees are both good ideas.

I’m not saying UBI can’t be done, but economists I trust have serious concerns about Big Data’s versions of it.

IMHO, federal job guarantee is superior.

I know we want to constantly site “automation” as the reason for these job losses but that simply is not the case. The NBER (National Bureau of Economic Research) found that since 1999 the number of workers displaced by increasing Chinese imports alone was 2.65 million workers. The number displaced by “robots” was 1.4m. And from 1999 to 2016, despite a falling unemployment rate, the overall annual employment-to-population ratio fell from 64.3 percent to 59.7 percent, a decline of 4.5 percentage points. Rather than rush to this dead end job “solution” why not fix the actual problem of outsourcing, which is doing a great job of depressing working class wages and increasing income disparities between the working class poor and the “professional class”, who are somehow sheltered from the blessed all knowing, all seeing “free market”.

But Duane, closing the outsourcing and bringing “it” back will only increase the adoption of the automation now that Chinese wages (plus global shipping costs) have set a new cost floor. Not saying it wouldn’t still be a good idea, just saying that the two are not mutually exclusive