Bay View Wetland Will Be Restored

One of city’s last wetlands, near Barnacle Bud’s, will be naturalized, may allow public access.

The project area includes land across a small channel from Barnacle Bud’s and land further east. Photo by Michael Horne.

Two centuries ago, before Milwaukee was settled, Milwaukee had 10,000 acres of wetlands, most of which have since been lost. But one of the last ones left, more than six acres on the east bank of the Kinnickinnic River that juts into the Milwaukee inner harbor, is about to be rescued and restored. The City of Milwaukee and the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources are entering the early stages of designing a habitat restoration for this degraded wetland.

Planners consider this effort at habitat restoration an important piece of a puzzle that links environmental sustainability and future economic development in the city. The area is just south of the confluence of the city’s three rivers — the Milwaukee, Menomonee and Kinnickinnic rivers — near the Port of Milwaukee. Funding has been secured for the design and planning of the wetland project, but not yet for the physical restoration efforts. A DNR analysis from 2016 estimated the potential cost at $2 to $6 million.

“A lot is going to depend on what happens with the state and federal budgets over the next few years,” says Benji Timm, a project manager with the Redevelopment Authority of the City of Milwaukee (RACM) which is coordinating the restoration efforts.

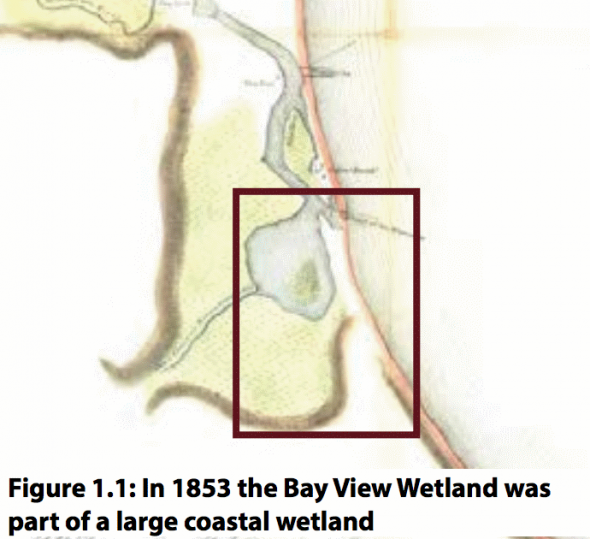

Milwaukee has been altering its wetlands and rivers since “the first commercial cargo vessel called at the struggling new village on the west shore of Lake Michigan,” as the city’s official history of the Port of Milwaukee notes. The biggest change came in 1857 with the “straight cut,” a new harbor entrance that “involved abandonment of the actual mouth of the Milwaukee River and construction of a new outlet a half mile to the north.” From then on Milwaukee’s burgeoning industry and population continued to alter the natural shoreline of Milwaukee’s port, impacting many habitats for native species along the way.

That includes the Bay View or “Grand Trunk” wetland, which is its official name. Since it was developed the wetland has served as “a lumberyard, salt storage warehouse, freight handling facility, railroad yard, and car ferry terminal,” according to the masterplan for its restoration. Its name, Grand Trunk, comes from the railroad company that operated a facility on the site loading rail cars on ferries for transport. Originally, the firm tried to fill in the whole 28-acre site that encompasses the wetland. But six and a half acres persisted. And on the site there is still undocumented fill and illegal dumping of solid wastes, construction debris, tires, and tanks.

“It’s this ecological treasure right in the middle of an industrial area,” Timm notes.

It is considered a seiche wetland, which means its levels fluctuate with those of the lake. And it’s the last wetland in the Kinnickinnic watershed with the potential to be restored as a functional seiche wetland, according to the DNR. This type of wetland is a critical habitat for spawning Northern Pike. But restoring it will also provide a better habitat for other bird and amphibian species that tend to dwell on the banks of rivers.

The Butler’s Garter snake is a threatened species native to the Milwaukee estuary. Right now, it’s “mostly absent” from most areas in the estuary, according to a DNR document, which identifies the species as a Species of Local Conservation Interest (SLCI). The master plan for the wetland restoration says the snakes in the wetland are “thought to be the last of this species in the estuary.” That plan highlights the installation of hibernacula or areas of refuge which could secure the population of these snakes.

The project would also make the site more amenable to other species, like burrowing crayfish and amphibians. And repairs to the riparian shoreline habitat would be important to “breeding and migratory birds and bats,” according to a DNR document. Right now there isn’t much natural shoreline, Timm says; it’s mostly sheet pile and dock wall.

Based upon the characteristics of the wetland, a number of state endangered species are likely to be there. Species like the peregrine falcon and a fish called the striped shiner. Others that are threatened or designated as a species of concern in the area include: the american eel and such fish species as the greater redhorse, longear sunfish and prairie crayfish.

The wetland is now home to phragmites or common reeds, which are a perennial grass and an invasive species that need to be removed. But it’s also home to a host of plant species that need protected habitats, like blue stem goldenrod, hairy beardtongue, harbinger of spring, hookers orchid, seaside spurge and marsh blazing star.

Key to restoring the wetland and the habitat is re-connecting the wetland and a channel running off the Kinnickinnic river. There’s a collapsed culvert that has filled with debris, blocking connection between the channel and wetland.

RACM recently put out an request for proposals soliciting bids from firms to design and plan the restoration and obtain permits. The undertaking will be no simple task. Any designs for restorative work will involve remediation of brownfield problems like contaminated soil and water, and must take into account potential invasive species, any regulatory considerations, and also the desire for the public to have access to the land once it is restored.

“A project like this is unique and will require a lot of patience and creative thinking,” Timm says.

The Harbor District, a non-profit working on revitalization of Milwaukee’s harbor, has partnered on the project to interface with the local community through meetings and updates. As they work through their own planning process for the area they have identified underused or vacant parcels that should be redeveloped. And the wetland is one of them. According to Lindsay Frost of the Harbor District, the group’s community meetings have found there is great interest in having public access to the wetland, in the manner of a park.

Frost says restoring the wetland goes beyond updating a parcel to its highest and best use and involves three concerns: first, the natural and cultural history of wetlands in the Milwaukee area; second, the moral obligation to restore a habitat for native species; and third, the potential for public access and thus public education.

The UW-Milwaukee School of Freshwater Sciences and College of Architecture and Urban Planning have been involved with the project, “since its inception,” according to the master plan. And researchers have studied the wetland for restoration efforts. And once restored, the site will be available for study by future generations of students.

The wetland is really a piece of a 28 acre site and bounded still by industrial and commercial uses. Nearby is Skipper Buds, which offers slips for boaters, and Barnacle Bud’s, a restaurant on the water. Part of the redevelopment of the Harbor District will involve new residential buildings and hotels. And with nearby residents and community groups already in favor of an accessible wetland, it could be a potential amenity for future developments.

The project is strictly classified as habitat restoration, and Timm notes that working on an environmental restoration is a unique project for a City agency, RACM, that normally focuses on economic development. But in reality the wetland shouldn’t be thought of completely isolated from future development, he adds. It already is bordered by urban business and land use and can help foster development. “This can be an asset,” he says.

In fact, while the city was developing the project’s planning document, students from UWM designed environmentally sustainable buildings that could be developed on a southwestern corner of the site.

With different land uses come different types of runoff, says Stacy Hron of the DNR. Planners will have to account for different pollutants in the runoff, even different types of invasive species more prevalent in disturbed areas like the industrial land surrounding the wetland.

Hron is the coordinator for the DNR’s efforts on the Milwaukee Estuary Area of Concern (AOC). And the Bay View wetland is one piece of a larger effort to clean up and remediate all the environmental damage that has occurred in the AOC. This effort began in 1987, and in 2008 it was expanded to address sites that were directly influencing the level of contaminated sediments in the AOC.

The scope of the the AOC is a reminder that, while important, the Bay View wetland is jockeying with other environmental projects just in the Milwaukee region, much less beyond the city. And that means limited resources.

In short, the amount of funds raised for this effort could determine whether the project can afford to take on tasks like building the public infrastructure that ensures public access to the wetland. And the project involves so many concerns that it may be some time before the wetland restoration is completed.

If you think stories like this are important, become a member of Urban Milwaukee and help support real, independent journalism. Plus you get some cool added benefits.

Places like this, designed to attract nature and wild animals are great especially when you see what impact a little swath of land can have. Hopefully folks will be understanding when the wild animals show up though. Coyotes will find there way to this area and they will prey on any smaller creature that is available to their disposal.

Kudos to Milwaukee and the DNR. The wetland restoration will be a great asset.

The entire area in yellow should be restored. There should be no development. None. There should be trails and natural shores. People should be able to fish and birdwatch and just explore. There should be another branch of the Urban Ecology Center. As time goes by, it should be expanded as far as possible. No development, no industry..

I’d love to see the original mouth of the river restored, obviously keeping the harbor channel for shipping purposes.

Thank you for writing this informative article. Great news.

Deer Creek historically had origins and remnants still in place in St. Francis, and followed Delaware Avenue north to meet up with this huge wetland. I have a 1901 Topographic map that shows this little river that joined the others forming the estuary all of the main rivers. Delaware Avenue was filled, and the small river sent underground in pipes.

I second the Urban Ecology Center idea. How do we make that happen. Tony Z??? Where’s Tony Z?

I work at Barnacle Bud’s and am thrilled at this idea! To reply to the comment about wildlife showing up that has been the case for many years. I work through the winter and have watched coyote cross the frozen river, we had a coyote, during dinner hour, swim across the river to snatch a gosling from its family. A hawk, during lunch hour, swoop down and snag a baby rabbit and watch the people watch him/her do its thing. We have had deer in the parking lot, deer in the river. Recently this spring we viewed a Black Crowned Night Heron perched across the way. Wildlife is nothing new to that area.

Does this project benefit water quality such as acting as a natural filter? Does it enhance the absorption of runoff during heavy storms?

Wetlands at lake level would do almost nothing to prevent flooding up river. This wetland improvement provide habitat that has been destroyed for repopulation of fish species that are native to the estuary, habitat for plants, birds, and insects.

The harbor fill area to the east is the largest migratory bird stopping watching place in the state. Over 200 species identified by bird watchers every season along this major flyway.

Flood protection with wetlands, detention basins, trees, rain gardens, and uplands is an important part of the mix. One mature Oak Tree can drink up 300 gallons of water per day. One mature deep rooted native prairie plant can account for 1-gallon of water per day.

Wetlands at lake level would do almost nothing to prevent flooding up river. This wetland improvement provide habitat that has been destroyed for repopulation of fish species that are native to the estuary, habitat for plants, birds, and insects.

The harbor fill area to the east is the largest migratory bird stopping watching place in the state. Over 200 species identified by bird watchers every season along this major flyway.

Flood protection with wetlands, detention basins, trees, rain gardens, and uplands are an important part of the mix. One mature Oak Tree can drink up 300 gallons of water per day. One mature deep rooted native prairie plant can account for 1-gallon of water per day.

I am currently listening to trees being culled across the river by the WE Energies company. There will be some displaced wildlife. Hopefully they can relocate somewhere!

Will miss seeing the cormorant colony in their tree.