Measuring Wisconsin’s Gerrymandering

Data shows why the court struck down state's map; “efficiency gap” not the reason.

In 1812, Massachusetts Governor Elbridge Gerry earned a type of immortality for his work in redistricting a legislative district centered on the town of Essex. A cartoonist mocked the district for its similarity to a salamander.

Ever since, “gerrymander” has been the common name for what is described by the American Heritage New Dictionary:

To change the boundaries of legislative districts to favor one party over another. Typically, the dominant party in a state legislature (which is responsible for drawing the boundaries of congressional districts) will try to concentrate the opposing party’s strength in as few districts as possible, while giving itself likely majorities in as many districts as possible.

Recently the term “pack and crack” has come to describe the strategy underlying gerrymanders. Concentrating the opposing party in as few districts as possible is called “packing”; breaking up a district leaning toward the opposing party and distributing those voters into a larger number of other districts is “cracking.” Cracking and packing are really part and parcel of the same thing: packing permits cracking.

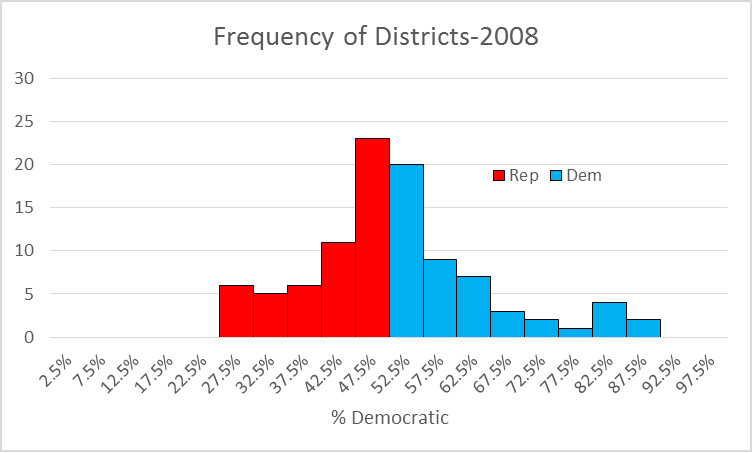

The next two charts illustrate how packing and cracking worked in Wisconsin. The first chart shows the distribution of Wisconsin Assembly districts according to their percentage of Democratic voters in the 2008 presidential election. The district boundaries were set by a panel of federal judges following the 2000 Census. While the districts range from 27.5 percent to 87.5 percent Democratic, there are by far the most in the middle range between 45 percent and 55 percent Democratic, making them very competitive for both parties. (A technical note: for these and the following calculations, I used the vote for a state-wide candidate—president or governor—adjusted for a tied election.)

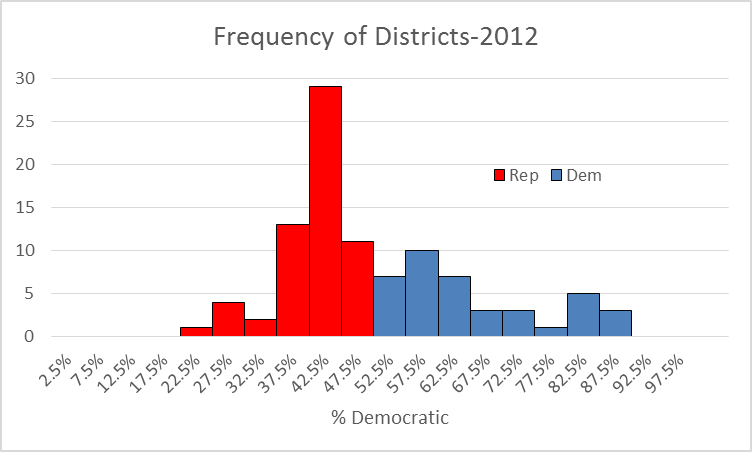

The second chart shows distribution of Assembly districts after the Act 43 2011 redistricting by Republican legislators. Packing and cracking created more Republican-oriented districts and safer Republican districts. Already-heavily Democratic districts became more heavily Democratic. Now you can see by far the most districts are 37.5 percent to 42.5 percent Democratic, giving Republican candidates a big enough margin to be assured victory.

Gerrymandering in Wisconsin reduced the number of competitive districts, in which the margin of victory was 4 percent or less, from 34 to just five. The number of Democratic majority districts was reduced from 48 to 39, increasing majority Republican districts from 51 to 60.

One measure of fairness in government policy is the symmetry test. In short, government shouldn’t put its thumb on the scale to favor one party over another, meaning similar percentages of voters for each party should win similar numbers of seats.

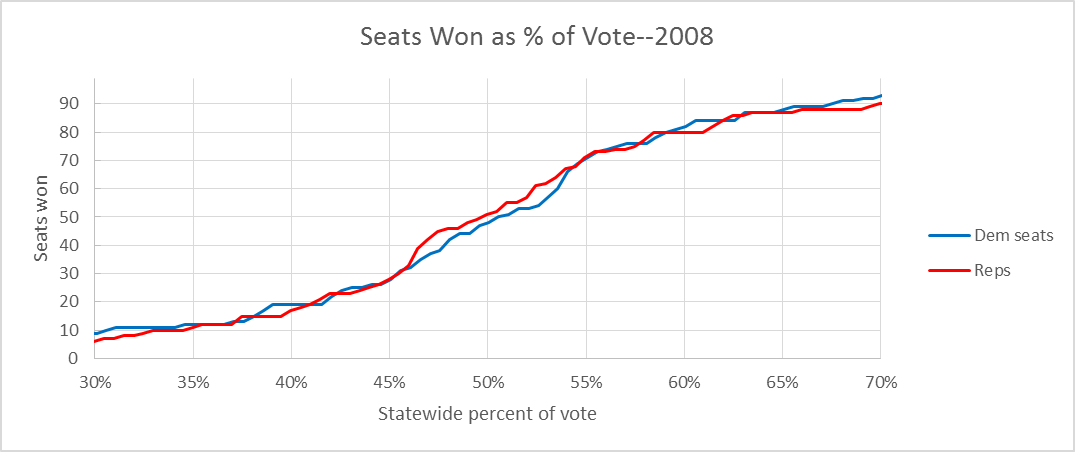

Under the symmetry test, the map drawn by the panel of judges following the 2000 census fares quite well. The next chart shows the estimated number of assembly seats each party would have won versus its overall vote percentage. In the 45% and 55% range, where most Wisconsin elections end up, the 2000 map plan gave Republicans an average four seat advantage. With strong candidates and smart campaigns this was a handicap that Democrats could—and sometimes did—overcome.

The next chart shows how much the gap opened as a result of the redistricting by the Republican legislators in Act 43 following the 2010 census. This gap is similar whether one uses the 2012 presidential election, shown by solid lines, or the 2014 election for governor, shown as dashed lines. Now there is a huge asymmetry between the two parties, one that strongly favors Republicans. Winning half the votes gives Democrats 39 seats and Republicans 60, based on the 2012 election.

That the curves from two different elections, the first won by a Democrat (Barack Obama) and the second by a Republican (Scott Walker), are so similar suggests the asymmetry is stable, stemming from the design of Act 43, rather than a difference among candidates in the two elections. From the Act 43 drafters’ viewpoint, asymmetry was an asset, not a defect.

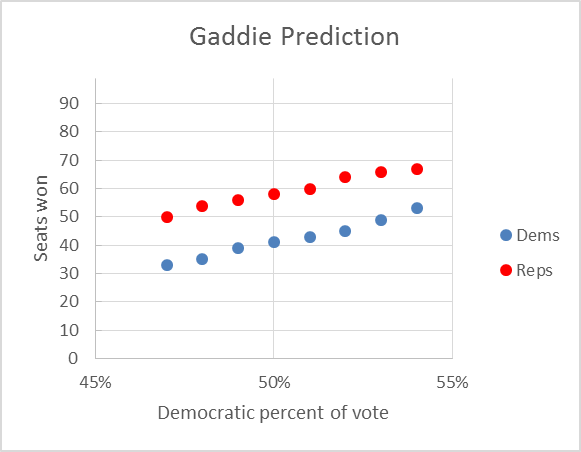

During the course of the recent litigation on Act 43, emails between the team hired by the legislature became available. The Republican advantage shown below was predicted by Prof. Ronald Gaddie, a consultant to the team drafting Act 43.

The challenge to Act 43 was considered by a three-judge federal court panel. Their decision overturning the Act 43 was written by Judge Kenneth Ripple and joined by Judge Barbara Crabb.

Judge Ripple starts with a review of US Supreme Court decisions on gerrymandering. Two previous cases are most relevant to Act 43: Bandemer in 1986 considered a gerrymander by the Indiana legislature; Vieth in 2004 challenged Pennsylvania districts. In neither case were the challengers successful.

The Supreme Court made a mess of the issue, offering no clear guidance for lower courts. The justices were unable to coalesce around a majority view. To over-simplify, one group wanted to entirely avoid challenges to partisan gerrymandering. A second would have ruled against partisan gerrymandering. Justice Anthony Kennedy, the potential tie-breaker opined that gerrymandering raised constitutional issues that could potentially be resolved with a consistent test.

The plaintiffs challenging Act 43 suggested a three step process:

- Was there a discriminatory intent or purpose?

- Did Act 43 have a discriminatory effect?

- Was there some other legitimate reason for the result?

The Wisconsin Department of Justice basically conceded the first and third points other than to argue that gaining a partisan advantage was normal. They were unable to offer any reason other than partisan advantage for the huge asymmetry. As the court concluded:

… the evidence establishes that one of the purposes of Act 43 was to secure Republican control of the Assembly under any likely future electoral scenario for the remainder of the decade, in other words to entrench the Republican Party in power.

Instead the state argued that compliance with traditional districting principles, including equal populations, reasonable compactness, contiguity, and following existing boundaries, creates a constitutional “safe harbor” for state legislatures. The three-judge panel concluded that: “the defendants’ contention—that, having adhered to traditional districting principles, they have satisfied the requirements of equal protection—is without merit.”

Having conceded points one and three, the state was left with arguing point 2, the effect. The court concluded that the actual effect was the intended effect:

Act 43 also achieved the intended effect: it secured for Republicans a lasting Assembly majority. It did so by allocating votes among the newly created districts in such a way that, in any likely electoral scenario, the number of Republican seats would not drop below 50%. … It is clear that the drafters got what they intended to get. There is no question that Act 43 was designed to make it more difficult for Democrats, compared to Republicans, to translate their votes into seats.

In arriving at this conclusion the court majority primarily used what it called “swing analysis.” Based on testimony of the outside experts as well as internal documents from the Act 43 team, it concluded that there was no reasonable way that Democrats could overcome the disadvantage Act 43 had established and swing the vote the other way.

Although most of the press coverage of the decision put an emphasis on the use of the “efficiency gap,” the decision itself makes it clear that this model played a secondary role:

While the evidence we have just described certainly makes a firm case on the question of discriminatory effect, that evidence is further bolstered by the plaintiffs’ use of the “efficiency gap”…

This model attempts to quantify the asymmetry caused by cracking and packing. It starts with the notion of “wasted votes.” All votes cast for a losing candidate are wasted, as well as half the vote a winning candidate gets in excess of his or her nearest opponent since those votes are not needed to win. In a two-candidate race, half the votes are wasted. The aim of cracking and packing is to inflict most of the wasted votes on the other party.

In Wisconsin the Act 43 gerrymander was aimed at entrenching Republicans; therefore it has been attacked by Democrats and defended by Republicans. It is easy to forget that partisan gerrymanders can be tools for either party that controls a state government and wants to maintain control even after losing public support. Also making its way through the federal courts is a challenge to a Democratic gerrymander in Maryland that flipped a Republican congressional seat to Democratic. When that case reaches the US Supreme Court, it will be interesting to see whether those criticizing the Wisconsin decision suddenly see the dangers of partisan gerrymandering.

With the development of highly sophisticated mapping software, packing and cracking has progressed far beyond the tools available to Governor Gerry. Unless the courts are willing to put some limit on their partisan use, there will be continued erosion of democracy in America. With Democratic votes much more likely to be wasted in Wisconsin, the historic principle of one person one vote is falling to partisan advantage.

More about the Gerrymandering of Legislative Districts

- Without Gerrymander, Democrats Flip 14 Legislative Seats - Jack Kelly, Hallie Claflin and Matthew DeFour - Nov 8th, 2024

- Op Ed: Democrats Optimistic About New Voting Maps - Ruth Conniff - Feb 27th, 2024

- The State of Politics: Parties Seek New Candidates in New Districts - Steven Walters - Feb 26th, 2024

- Rep. Myers Issues Statement Regarding Fair Legislative Maps - State Rep. LaKeshia Myers - Feb 19th, 2024

- Statement on Legislative Maps Being Signed into Law - Wisconsin Assembly Speaker Robin Vos - Feb 19th, 2024

- Pocan Reacts to Newly Signed Wisconsin Legislative Maps - U.S. Rep. Mark Pocan - Feb 19th, 2024

- Evers Signs Legislative Maps Into Law, Ending Court Fight - Rich Kremer - Feb 19th, 2024

- Senator Hesselbein Statement: After More than a Decade of Political Gerrymanders, Fair Maps are Signed into Law in Wisconsin - State Senate Democratic Leader Dianne Hesselbein - Feb 19th, 2024

- Wisconsin Democrats on Enactment of New Legislative Maps - Democratic Party of Wisconsin - Feb 19th, 2024

- Governor Evers Signs New Legislative Maps to Replace Unconstitutional GOP Maps - A Better Wisconsin Together - Feb 19th, 2024

Read more about Gerrymandering of Legislative Districts here

Data Wonk

-

Life Expectancy in Wisconsin vs. Other States

Dec 10th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Dec 10th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

-

How Republicans Opened the Door To Redistricting

Nov 26th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Nov 26th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

-

The Connection Between Life Expectancy, Poverty and Partisanship

Nov 21st, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Nov 21st, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

As usual, excellent article, Bruce!

I disagree with prong 1 and prong 3 of plaintiff’s 3 prong test. Prong 2 is proof alone of prong 1, provided that a less discriminatory map could have been made. And prong 3 can never be satisfied, or is a bit redundant. There is never a legitimate reason to choose a more discriminatory map over a less one, when both meet compactness, contiguity, and equal population.

There should be only one prong:

* is a significantly less discriminatory map that meets all basic requirements available?

Clearly this prong is satisfied: the previous map!

Efficiency gap can actually produce not only false, positives, but also false negatives, and can flip sign simply by the partisan swing shifting.

false positive: http://autoredistrict.org/blog/images/seats_votes_good_false_pos.png

false negative: http://autoredistrict.org/blog/images/seats_votes_false_neg.png

sign flip: http://autoredistrict.org/blog/images/seats_votes_sign_flip.png

More reading on gerrymandering: https://thinkprogress.org/democrats-may-already-be-blowing-the-2020-redistricting-fight-d7edf43703ac#.i8ixecz9t

There are times where I find myself searching for the “like” button ok Urban Milwaukee comments, and times where I wish there was a “love” button. This is the latter.

I’ve had the same thoughts as this author wrote, but lacked the skill to write them so clearly.

Butt to se someone else write them – so well – that is decidedly better! At least in feeling. To see someone else share it – even better!