Baby Boomers Who Are Homeless

As this generation ages, they increase number of older homeless, who face unique challenges.

Tom Church lost everything.

He was in his early-50s and homeless, sleeping on cold concrete and surviving on food stamps. He wandered in and out of shelters, until someone suggested that he try the Guest House of Milwaukee’s substance abuse counseling program. His decision to check it out saved his life.

“Really, if I hadn’t found the Guest House, if I was still living on the street, or quite possibly several other places — I just would have died,” Church said.

Church suffered a major heart attack while at the Guest House, and doctors saved his life by giving him a heart pump. Fortunately, Church was no longer living on the street. The pump required a battery charge each night.

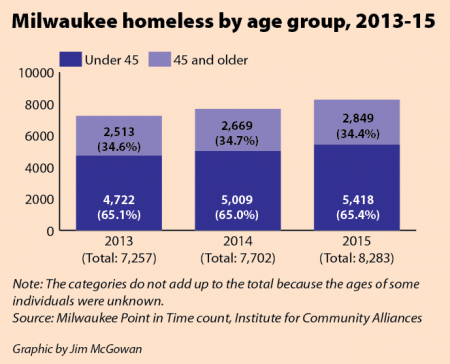

More than 30 percent of the 5,355 homeless individuals in Milwaukee emergency shelters were older than 45 in 2015, according to the Institute for Community Alliances, a nonprofit that researches and produces reports on homelessness and related issues.

The percentage of homeless people over 45 has remained consistent over the past three years (2013 to 2015) at about 34 percent. In the same time period, the number of homeless individuals over 45 increased from 2,513 in 2013 to 2,849 in 2015 (see graphic).

National trends show “older folks becoming homeless later in life,” said Eric Collins-Dyke, outreach services manager for the Milwaukee County Department of Health and Human Services’ Housing Division. “They may not have the family support, they may not have the social system that a younger person might have, and we certainly notice that they are the most vulnerable on the street in terms of health disparities,” he added.

A paper released in 2010 by the National Alliance to End Homelessness attributed the projected increase in older adults who are homeless to the size of the aging baby boomer population and the steady rate of economically vulnerable people over 50.

Cindy Krahenbuhl, executive director of the Guest House, said the average age of a shelter resident there is 45-55. This population brings unique challenges, such as chronic health conditions and a need for more resources.

“We have people who have been on chemotherapy, people who have been on dialysis,” Krahenbuhl said. “We’ve had people who would go for gall bladder surgery or knee replacements. … and the only place they have to come is either the street or back to the Guest House.”

There are few services geared to homeless people over the age of 45 in Milwaukee or nationally.

“I think people don’t understand that there are people in this age category and above that are homeless,” Krahenbuhl said. “For some reason I think that they just think it doesn’t really happen for someone in that age group.”

“You just start disintegrating”

Dr. Margot Kushel has spent nearly 20 years researching and working with older homeless adults in Oakland, California.

Her study, the HOPE HOME project, tracks 350 adults over age 50 through extensive interviews conducted six months apart. The study is funded by the National Institute on Aging and is conducted through the University of California San Francisco.

In addition to asking questions about life course, jobs, shelter and social services, Kushel’s group performs health assessments on the participants, measuring their brain function, balance, vital signs and other indicators. The study found that homeless adults are sicker than other people their age.

“People who are over 50 and are homeless look (physically and mentally) more like 70,” Kushel said.

Tom Church plays the guitar in his apartment, nearly 10 years after he was homeless for the first time. Photo by Devi Shastri.

Church, who now lives in an apartment, also noted his worsened physical condition while on the streets. “You know, a younger body can take more,” he said. “It’s a lot more resilient. … (When you’re older) you just start disintegrating. You don’t get the proper exercise.”

Two years into the study, Kushel has found that people lost their housing due to a variety of experiences that people encounter as they age. These include the death of a spouse or parent, job loss or eviction while they were serving time in jail.

Physical and cognitive impairments disproportionately affect older people who are homeless, the study found. Arthritic patients had trouble walking long distances to get from shelter to shelter and those with cognitive issues had trouble remembering tasks recommended by caseworkers or doctor appointments.

Often Kushel’s subjects ended up in the emergency room for manageable issues that had gotten out of hand.

Kushel also found that 44 percent of the participants had never been homeless as an adult until they were 50. Another 20 percent were homeless for the first time in their 40s. Throughout the study, 80 percent of the participants have remained homeless. Fourteen have died. Many more are very ill. Yet, she found they do not want to ask for support.

“A lot of the people are very, very ashamed that they are homeless,” Kushel said.

The result is increased rates of depression and anxiety in a population that is physically, mentally and economically disintegrating.

A new outlook

In the nondescript yellow house on Ninth Street that holds St. Ben’s Clinic for the Homeless, social worker Bill Mullooly sips his coffee after a day working with patients. He has worked at the clinic for two decades and has watched housing conditions change significantly in the city during that time.

“Underlying homelessness is the lack of affordable housing,” Mullooly said. “Back in the ’50s and ’60s and ’70s, (the idea was) one week’s work should equal one month’s rent.”

He explained that expensive housing and low wages make addiction more crippling because people have to spend more than half their paycheck on rent while driven by their illness to spend money on alcohol or drugs. Mullooly said the city’s new Housing First Initiative is helping by getting people shelter and dealing with issues such as addiction later. He also praised the benefits of government-issued cell phones and the Affordable Care Act.

Other new initiatives in the city include Impact 2-1-1, a hotline that allows those who are homeless or at risk of becoming homeless to find multiple shelter options in one place. Project Homeless Connect at Marquette University, an annual daylong event, provides healthcare, haircuts, job information and many other resources to Milwaukee’s homeless.

“I have seen some great partnerships develop,” said Nancy Monarrez, Milwaukee’s director of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s Homeless Management Information System. “Milwaukee is really good at … finding a problem, and then looking at the solution and saying, ‘This could work, but there’s a better solution.’”

Better mental health resources for homeless people are critical, according to those who work with this population.

The Affordable Care Act also has helped homeless individuals deal with chronic conditions, noted Monarrez.

“Once you’re insured and you’re able to locate a primary care physician you can take care of those health issues: high blood pressure, diabetes, high cholesterol,” Monarrez said. “If you maintain a good diet and your regular checkups, (those conditions) are more manageable.”

The main solution to the struggles of many older adults, however, may be the most obvious: to provide affordable and supportive housing. Since September 2015, the Housing First program has housed 107 people who meet the criteria for chronic homelessness, 85 percent of whom are over 40, and 65 percent over 50. One-fifth of those housed through the program are over 60 years old. While the program does not require it, all 107 are in case management.

“We’ve noticed, since they’ve been in housing, that a lot of the health stuff doesn’t necessarily go away but it stabilized quite a bit,” Collins-Dyke said. “We can get them connected to medical care … they’re not using as much, they’re able to get medication for diabetes or arthritis … they have a medicine cabinet now to keep their medicine in.”

While Kushel praised such programs, she pointed out that the best way to help older people is to keep them from becoming homeless in the first place.

“Unless we are willing to see more people who are 50 or older on the streets, we need to do something about the fact that a fourth to a third of people are spending more than 50 percent of their income on housing,” Kushel said. “Leaving these people on the streets is not a sign of a civil society.”

This story was originally published by Milwaukee Neighborhood News Service, where you can find other stories reporting on fifteen city neighborhoods in Milwaukee.