Is ObamaCare Working in Wisconsin?

Yes, because Walker used one part of Obamacare to replace what he rejected.

The two most important and controversial provisions of the Affordable Care Act took effect at the beginning of 2014—expansion of Medicaid and introduction of the exchanges. How has it fared since, both nationally and in Wisconsin? Far better than Republicans have claimed, which continues to leave them no policy alternative.

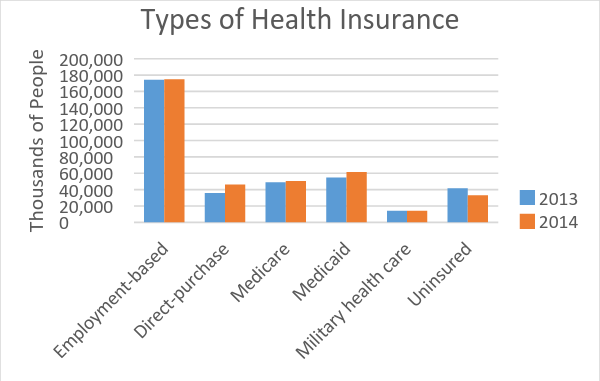

Recently the US Census Bureau released estimates for the number of Americans of all ages with and without health insurance in 2014. The percentage of people without insurance dropped from 13.3 percent in 2013 to 10.4 percent in 2014.

The chart to the right shows how people obtained their insurance. Not surprisingly, the two biggest increases were direct purchase of insurance and Medicaid.

While the Census estimate is limited to 2014, available evidence indicates the number of people without insurance continues to decline. The latest estimate from Gallup-Healthways is that the percentage of adults without insurance hit 11.4 percent in the second quarter of 2015 compared to 18 percent in the last quarter of 2013.

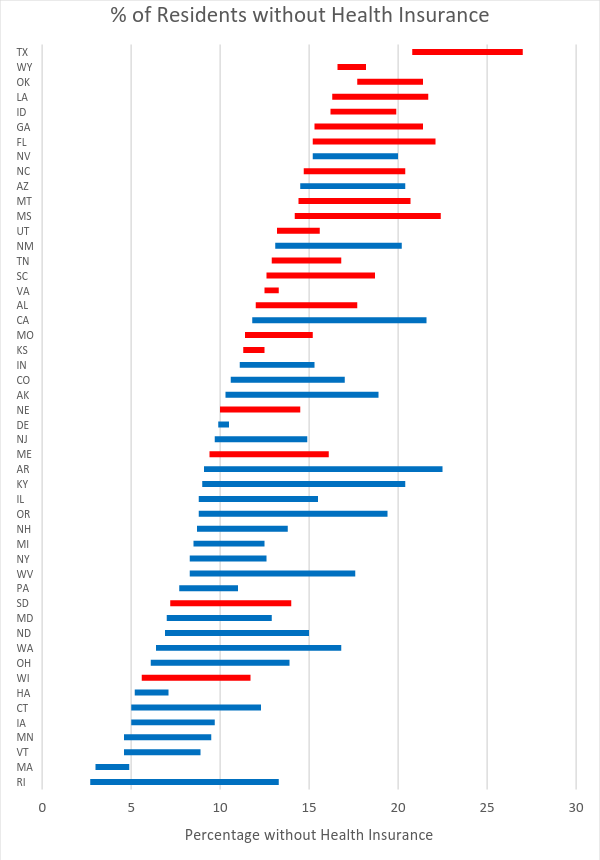

Every six months Gallup releases data for the states, and its most recent estimates show the percentage of residents without health insurance in each state for the first half of 2015. The chart to the right compares Gallup’s 2015 estimates with their results for 2013, before the major ObamaCare provisions took effect.

The color of bars indicates whether or not a state adopted ObamaCare’s Medicaid expansion, according to a tabulation by the Kaiser Family Foundation. Blue means the expansion was adopted; red that it was not. In a few cases, it is not clear from the foundation’s footnotes whether the expansion had been in place long enough to affect enrollment numbers.

The states are ordered in decreasing percentages of residents without health care for the first half of 2015. Texas, at the top, has the most residents lacking insurance; Rhode Island, at the bottom, has the least lacking insurance. Thus the left end of the bars are the most recent percentages (except for Wyoming, where Gallup shows a slight increase in the percentage without insurance).

The right ends of the bars shows the percentage uninsured back in 2013, before ObamaCare kicked in (except for Wyoming). Thus the length of the bars show how much the percentage of uninsured declined (or increased for Wyoming) from 2013 to 2015.

Gallup polls all year, so the sample sizes for 2013 are about twice as large as those for 2015. The sample sizes vary with the size of the state. Several small states have 2015 sample sizes under 300, compared 8,600 for California. The larger error associated with small samples may help explain why Wyoming showed an increase in uninsured people and why Rhode Island’s fell so dramatically.

Not surprisingly, states expanding Medicaid have lower uninsured rates as a group. Interestingly these states also had lower uninsured rates before ObamaCare kicked in, presumably reflecting a different political culture and attitudes about whether or not a state has a responsibility for the welfare of its residents. The states that have not expanded Medicaid are heavily concentrated in the South and the Plains.

The states that expanded Medicaid but still have relatively high rates of uninsured residents are in the Southwest (California, Nevada, Arizona, and New Mexico). This likely reflects in part the concentration of Hispanics, especially undocumented immigrants who are ineligible for ObamaCare.

Wisconsin stands out among the states rejecting the Medicaid expansion, with both a relatively low uninsured rate and a healthy drop in the percentage of uninsured people after ObamaCare took effect. It was 8th lowest among the states based on the percentage of uninsured people in 2013 and maintained that rank 2015.

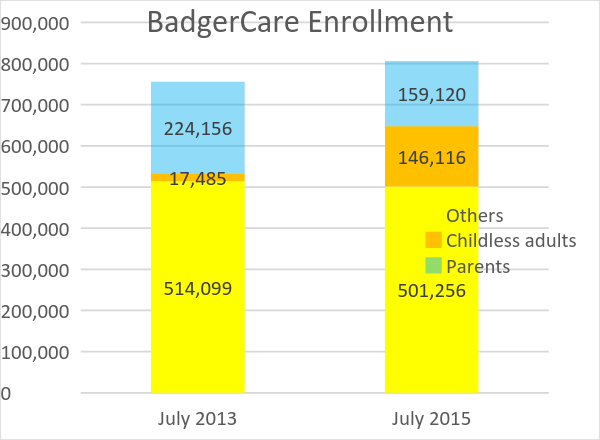

In essence Wisconsin did expand Medicaid, but at a higher cost to state taxpayers than necessary. It did this by pushing out parents whose income made them eligible for subsidies on the ObamaCare exchanges to make room for low-income adults without children, as the chart on the right shows. In addition, total BadgerCare enrollment increased by about 50,000.

While this decision was fiscally questionable, it does not seem to have hurt enrollment numbers. It did serve to keep Governor Scott Walker acceptable to the Republican base, but at a cost to state taxpayers over four years estimated at $500 million. It is also a model that only worked because Wisconsin had a relatively low number of uninsured low-income residents, and because another ObamaCare innovation—subsidized private insurance purchased through the exchanges—was available for those dropped from BadgerCare.

Thus the state that was arguably most successful in rejecting one part of ObamaCare did so only by leaning on another part of ObamaCare. This suggests why Republicans have been unable to come up with an ObamaCare replacement. They have set up a list of constraints that makes it impossible to come up with a replacement no matter how much time and how much thought they put into the problem.

Among the constraints a Republican replacement for ObamaCare must satisfy are no new taxes, no individual mandate, and the freedom to buy any health care policy, including across state lines. However, to be politically viable a plan should also not cause the percentage of uninsured to rise, it should not cause insurance to become unaffordable, and there should be no exclusion for pre-existing conditions, among other things. The continued decline of the number of uninsured people under ObamaCare makes the challenge steadily greater.

Any system of universal health insurance requires healthy, low-risk people to subsidize sick, high-risk people. Worldwide, most systems of health insurance use taxes to redistribute money from healthy people to sick people, whether the single payer systems in Canada, National Health in Britain, or the variety of plans on the continent. ObamaCare uses a different system of redistribution: community rating, so that insurance companies cannot set different prices based on how healthy a person is. This essentially sets in motion a cross-subsidization from healthy people to those needing more health care.

However, a core promise made by Republicans is that their replacement plan will remove all the ObamaCare regulations that make community rating feasible—such as the minimum services that must be provided and the individual mandate—and would allow insurance companies to compete for the healthiest customers. But if every individual is paying rates based on the the costs they are likely to incur, sick and risky individuals will find insurance unaffordable.

This means that taxes will have to be raised if the Republican promises to the public that everyone will have affordable insurance are to be fulfilled. However, most Republican legislators have signed a pledge not to raise taxes. Through their promises and slogans, Republicans have locked themselves into a situation where there are no feasible solutions. To make it feasible, they must break some of their promises. It will be interesting to see which they decide to break. Or they may just go on promising a replacement that never emerges.

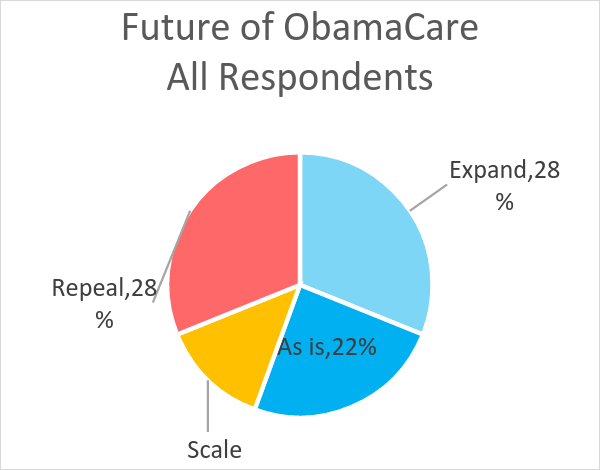

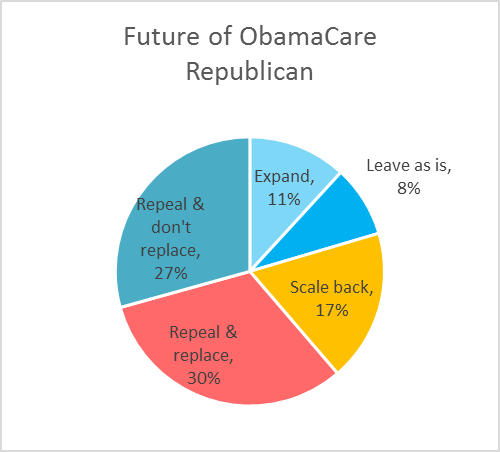

Besides the issue of the feasibility of a Republican replacement for ObamaCare another obstacle is the attitudes of the Republican base. In its most recent poll, the Kaiser Foundation asked people whether they want to expand ObamaCare, leave it as is, scale it back, or repeal it. As the chart shows, only 28 percent of those picking one of the choices opted for repealing the law.

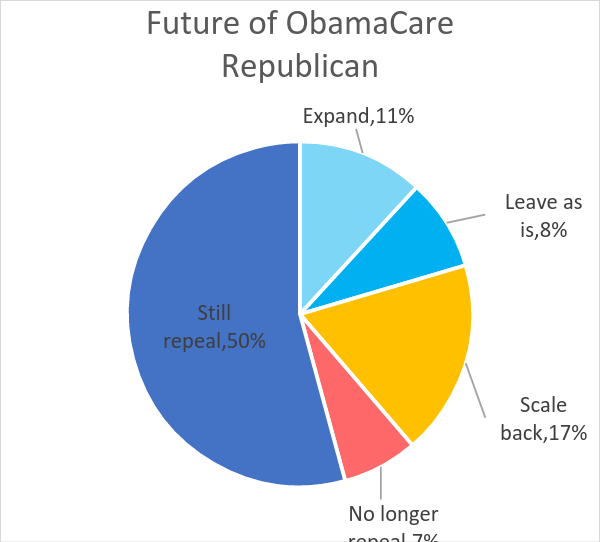

With Republicans, however, responses were quite different. A majority opted for repeal. The survey asked all respondents opting for repeal whether or not they wanted to replace it with a Republican-sponsored alternative. As can be seen in the next graph, only a slight majority wanted a replacement.

Those opting for repeal were also asked whether they would change their position if they heard that about 19 million people would become uninsured if the health care law were to be repealed. Only 3 percent switched, as shown in the next graph.

As soon as an ObamaCare replacement gets specific, the contradictions between the various goals become evident, as demonstrated by the Walker replacement proposal. Thus those awaiting a Republican replacement for ObamaCare are likely to have a long wait.

Data Wonk

-

Life Expectancy in Wisconsin vs. Other States

Dec 10th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Dec 10th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

-

How Republicans Opened the Door To Redistricting

Nov 26th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Nov 26th, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

-

The Connection Between Life Expectancy, Poverty and Partisanship

Nov 21st, 2025 by Bruce Thompson

Nov 21st, 2025 by Bruce Thompson