Federal Funds Decline for Area Non-Profits

PPF study finds 7 of 9 local community groups suffered at least 10 percent cut.

Federal funding has declined for home renovation projects such as this one at 737 S. 36th St. Jeremy Belot coordinates real estate development for Layton Boulevard West Neighbors. Photo by Matthew Wisla.

Everything about the house next to Shawna Clarmont’s home on the South Side threatened the health of the neighborhood. Before the bank foreclosed on the house and it became a vacant eyesore, the residents were known to be a disreputable collection of hoarders and drug users who never lifted a finger to maintain the property. The siding was made with asbestos, a known carcinogen.

“Everyone knew the house was a wreck,” said Jeremy Belot, director of real estate development at Layton Boulevard West Neighbors (LBWN). But one recent morning after Clarmont returned home from working her third-shift job, she pointed toward the house and called out with a big smile, “Hey Jeremy, looking good!”

Layton Boulevard West Neighbors bought the house on 36th Street in the Silver City neighborhood last winter and is making major repairs and upgrades, including new siding, as part of a program that renovates vacant properties previously owned by the city or a bank and sells them to families.

Government funding for the HOME Program, which helped rehab this house at 724 S. 38th St., declined 34 percent between 2006 and 2014. Photo by Matthew Wisla.

However, government funding that helps support this and similar programs throughout the city has been in significant decline, creating increasing pressure on community organizations to identify more stable, sustainable sources of funding. According to a new report by the Public Policy Forum, “Public Funding for Community Development in Milwaukee,” from 2007 to 2015 government funding in seven of the nine programs tracked decreased by at least 10 percent.

The report looked at programs in three areas: housing and development, education and workforce, and health and human services. It was commissioned by the Zilber Family Foundation and United Way of Greater Milwaukee & Waukesha County.

“The recession played a role (in decreased funding) but so did changing government priorities and a trend where federal money that would previously go mostly to Milwaukee is now being allocated more widely around the state,” said Rob Henken, president of the Public Policy Forum.

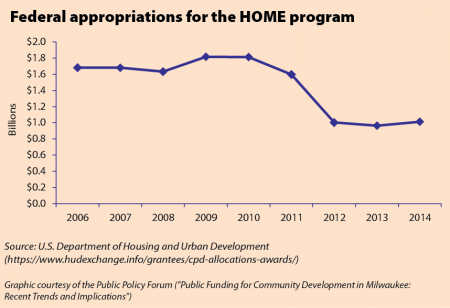

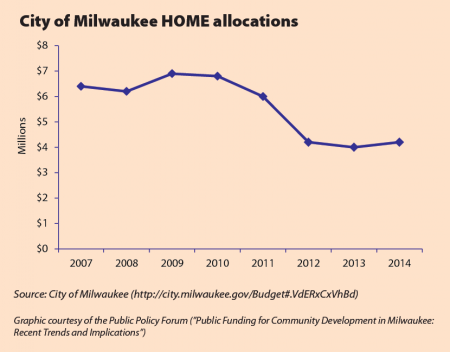

The house next to Clarmont’s is being rehabbed in part with funds from the federal HOME Investment Partnership Program. Funding for HOME has declined nationwide by 40 percent (see chart, “Federal Appropriations for the HOME program”) and Milwaukee allocations followed suit, falling off 34 percent between 2006 and 2014 (see chart, “City of Milwaukee HOME allocations”).

Subsidies are critical

Belot points out that the project will turn “the worst house on the block into one of the best” and contribute to neighborhood stability, but the transformation takes significant investment. After purchasing the house for $22,000 in February, Layton Boulevard West Neighbors is putting approximately $180,000 into repairs and upgrades. It hopes to put the house up for sale in early September for about $100,000. The difference between the sale price and the amount spent comes from government subsidies or other fundraising.

Nicole Angresano, vice president of community impact for United Way of Greater Milwaukee & Waukesha County, has seen the impact of reduced funding. “Many organizations have taken a pretty big hit,” Angresano said.

The Milwaukee Christian Center, for example, has said it plans to only rehab half the number of homes this year as it did in 2007 due to decreased federal funding from Community Development Block Grants. According to the report, funds to Milwaukee from that federal program dropped by 18 percent between 2007 and 2015.

In addition to housing projects, public health initiatives also are affected, although the need hasn’t decreased and the community organizations delivering services are performing well, according to Angresano. For example, she said federal programs to combat domestic violence have been slashed with little or no warning as part of the reduced funding trend.

Some local programs and organizations are facing funding cuts even as federal allocations to Wisconsin increase or remain the same. That happens when rising needs around the state draw funds away from Milwaukee. For example, Title 1 provides funding support to school districts with a high percentage of low-income families. Started in 1965, it is the largest federally funded education program for elementary and secondary schools. Between 2007 and 2014, federal Title 1 allocations to Wisconsin remained steady but Milwaukee Public Schools received about $12 million (14 percent) less while other school districts around the state saw increases. According to the report, Title 1 funding is “critical” to Milwaukee Public Schools, making up approximately 6 percent of its overall revenue budget.

“These funding shifts (that disperse money more widely throughout Wisconsin) are happening a lot more than they used to,” Angresano said.

Ongoing changes in demographics and poverty levels around the state are likely to continue challenging the ability of local organizations to secure funding regardless of the size of the population or severity of the need in Milwaukee, according to Angresano and others. That’s partly because many federal programs, including those studied in the Public Policy Forum’s report, allocate funds based on set formulas.

“Money is tight and Milwaukee is increasingly in competition with other communities around the state,” said Ian Bautista, executive director of the Clarke Square Neighborhood Initiative. “I wish the federal government prioritized neighborhood investment more.”

New options

With government funds waning, community organizations are under pressure to identify new revenue streams. According to Bautista, the funding squeeze “puts them more in a position to seek private funding or cut back on programming.”

The Public Policy Forum agrees that there is a new emphasis on local private sector support and also identifies “service innovations” as a way organizations are addressing the challenge. For example, Layton Boulevard West Neighbors is using volunteer labor wherever possible to help rehab houses. Area contractors willing to donate their time are scheduled into the workflow of projects, according to Will Sebern, executive director of LBWN.

Organizations also are looking at more significant changes to make their funding models more predictable and sustainable. Angresano has been recommending an increased focus on business development to the organizations she works with.

“It’s increasingly a priority to have a high-quality development person on staff who can look at an organization’s funding options and develop a roadmap,” she said. “You have to remain mission-aligned and not start looking for grants outside your core mission.”

According to Sebern, partnerships are key. “For the future, what’s clear is a need for building partnerships with other organizations in the community if you want to maintain your organization and services and grow,” he said.

Bautista added that conditions might be right for some organizations to consider merging. “Sometimes larger organizations weather storms more easily,” he said.

This story was originally published by Milwaukee Neighborhood News Service, where you can find other stories reporting on fifteen city neighborhoods in Milwaukee.