Why is Wisconsin Last in Startup Businesses?

The state’s backward-looking business culture may be to blame.

Early in June, Kansas City’s Kauffmann Foundation released its 2015 index of startup activity. The news was not good for this state. Wisconsin fell to last place: 50th among the states, from 45th last year. The Milwaukee-Waukesha-West Allis metropolitan area was 39th of the 40 largest cities, the same as last year.

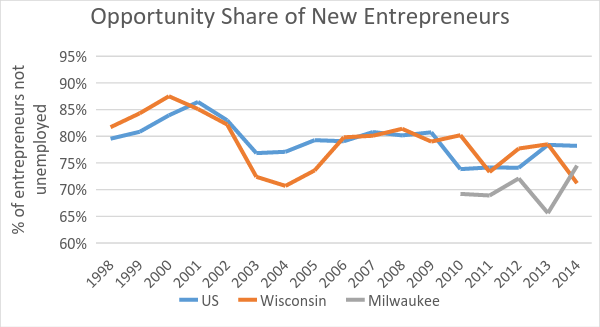

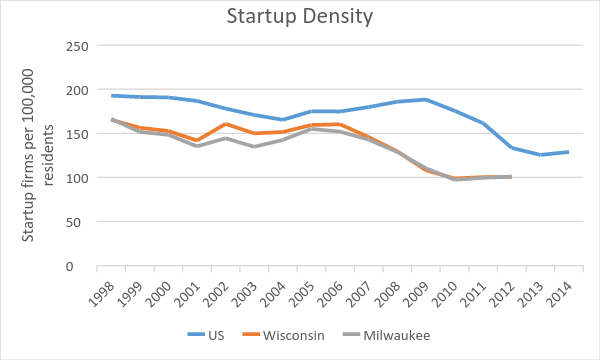

The 2015 index is based on three variables: rate of new entrepreneurs, opportunity share of new entrepreneurs, and startup density. These are measures of overall entrepreneurship and not limited to those in high-tech startups. (The foundation plans to add four more variables later this year.) The three graphs below show these measures over time for the U.S., Wisconsin, and the Milwaukee metro area.

Kauffmann describes the rate of new entrepreneurs as an “early and broad measure of business ownership.” It is calculated as the percent of the adult population of an area that became entrepreneurs in a given month.

Up until the start of the recession, Wisconsin performed at the national average. It then fell off and has continued to decline.

The opportunity share of new entrepreneurs is the percent of new entrepreneurs who were not unemployed. Kauffmann’s rationale for this is these are people starting a new business because they saw market opportunities, not out of economic necessity.

Wisconsin closely approximates the national average on this measure. Milwaukee seems to run a bit below the national and state measures.

The third measure, the startup density, is the number of startup firms per 100,000 resident population. It counts firms less than one-year old and employing at least one person besides the owner. For states and metro areas, it is available through 2012.

The Wisconsin and Milwaukee startup densities look similar: both have performed well below the US average.

The Kauffmann report compares entrepreneurial outcomes; it doesn’t speculate on the causes for the differences. It tells states and cities how they are doing, not how to do better.

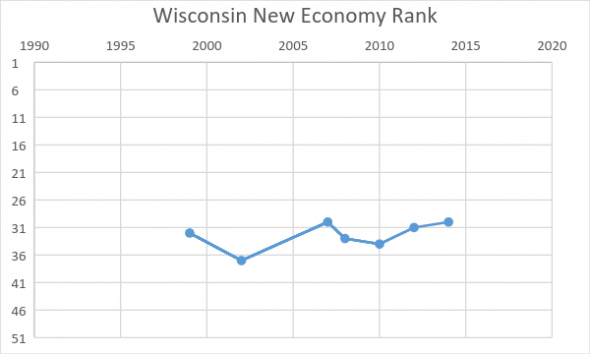

One index that tries to get at the question of how states can encourage entrepreneurship in technology is the New Economy Index, issued every two years by the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation. It uses 25 indicators to measure the extent to which state economies are “knowledge-based, globalized, entrepreneurial, IT-driven and innovation-based.” It was first issued in 1999. As the chart to the right shows, Wisconsin’s rank among the states has hovered in the low 30s, below average, for most of its history.

The economist Edward Glaeser argues that the strength of cities is their ability to spur innovation by facilitating face-to-face interaction. Using Detroit as an example, he argues that the array of small businesses at the start of the 20th century allowed entrepreneurs like Henry Ford to flourish. Then, by putting all his operations under one roof, Ford, and others like him, destroyed Detroit’s reason for being.

In looking at the charts above, it is notable that there is little sign of changes in direction when state administrations change. From an entrepreneurial point of view, the Walker years are an extension of the Doyle years. The Doyle years, in turn, were an extension of the Thompson years. Thus one must look to Wisconsin’s culture, particularly the dominant culture of its business community, for an explanation for the state’s continuing mediocre performance.

Entrepreneurs are successful when they anticipate needs. When the environment changes, entrepreneurs look for opportunities. Old-line businesses often see change as threat and spend their energy fighting change. The dynamics of organizations representing business is that often their most energetic members are those most threatened. This helps explain the evolution of Wisconsin Manufacturers and Commerce (WMC) into an increasingly reactionary organization. (In the 1980s I attended meetings of the WMC environmental committee. The meetings were totally dominated by the paper industry, which was focused on fighting off proposed air and water regulations.)

As an example, consider the rules the EPA has proposed to reduce greenhouse gases resulting from electricity production. Because Wisconsin is heavily dependent on coal for electricity, WMC and its allies view these rules as a threat. So the MacIver Institute hired the Beacon Hill Institute at Suffolk University to write a report detailing the projected costs of the EPA proposal. It concludes that the proposal would cost Wisconsin $920 million in 2030, increase electricity prices by 19 percent, lower disposable income in the state by nearly $2 billion, and cost 21,000 jobs. When the report was issued, Wisconsin Manufacturers and Commerce repeated these claims on its website.

Beacon Hill does not spell out its methodology and assumptions, other than refer to its proprietary econometric model. However, there are reasons to expect the costs would be much lower. For one thing, Beacon Hill seems overly anxious to obtain the result its customer wants.

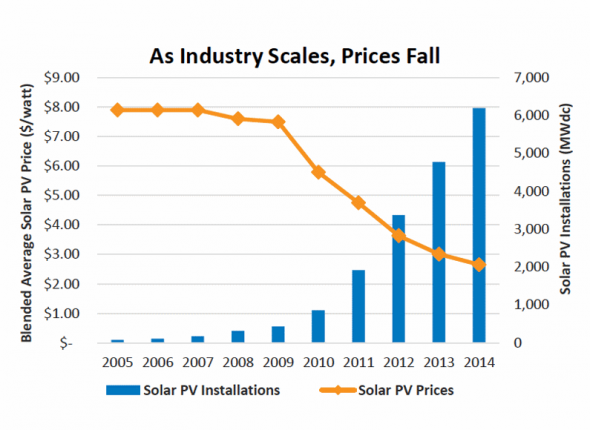

For another, there is no indication that Beacon Hill has taken into account the power of a market economy to come up with new technologies once the right incentives are in place. Solar power costs, for one, have dropped quickly as solar capacity has increased, as shown in the chart to the right, from a report by GTM Research for the Solar Energy Industries Association.

An entrepreneur could look at the Beacon Hill report and see opportunity. For example, spending $920 million translates into over ten thousand new jobs. But will they be created in Wisconsin or in other states or countries? Importing coal or gas to Wisconsin doesn’t create jobs here. Investing in solar or wind power does.

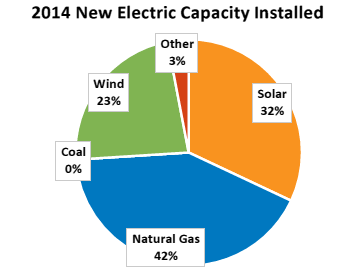

Even without the new EPA rules, electricity generation has been shifting away from coal, as shown in the next chart. Solar and wind power accounted for 53 percent of new electric capacity in 2014; coal accounted for 0 percent. The EPA rules, if implemented, will help drive demand for these already popular new technologies. Will that demand be satisfied by startups in Wisconsin?

As part of the stimulus package the federal energy department gave research grants to companies attempting to develop new energy projects. Sadly, none were in Wisconsin, as the following map shows. Instead the projects are concentrated in a few clusters.

It is tempting to blame the Walker administration for Wisconsin’s lagging entrepreneurial record. However, that record was in place long before he was elected. It may be that both the Walker program and the lack of entrepreneurial dynamism stem in part from the same cause: a backward-looking state business culture. Walker is giving top business leaders what they want, and the result is the continuation of a long-lagging record in creating new businesses.

Standard business advice to established companies is that they should take the lead in making their products obsolete. In practice, however, that advice is exceedingly difficult to follow.

There are a lot of factors that contribute to the success or failure of entrepreneurs, including luck. But the single most important is the ability to identify a market. A business environment hostile to measures to reduce the effect of global warming is hardly helpful in encouraging innovation.

Data Wonk

-

Why Absentee Ballot Drop Boxes Are Now Legal

Jul 17th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

Jul 17th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

-

The Imperial Legislature Is Shot Down

Jul 10th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

Jul 10th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

-

Counting the Lies By Trump

Jul 3rd, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

Jul 3rd, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

Thank you for all the logical data and detail. Well done.

During 2010, Wisconsin was ranked by ACEEE as a top 10 state regarding its commitment to energy efficiency and renewable energy. Walker and new PSC administrators came into the picture and Wisconsin has dropped to middle of the pack.

Consumer owned and operated projects for energy efficiency, solar energy, and integrated with best practices for major renovations of building could reduce energy consumption by 50% of fossil fuels in a few decades time. The status quo utilities oppose this approach since it would curtail the need for their investment in $3B of new fossil fuel produced energy.

Wisconsin sends over$13B annually out of state for purchase of energy. Cutting into this export of dollars cost would also spur the local economy, create thousands of small business new jobs that renovate buildings with energy efficiency and solar, and use many local materials.

Wisconsin is missing out on many new tracks due the toxic pall our least educated governor and legislature have inflicted across the state with the ALEC policies and laws.

Even better David, why don’t we stop buying energy from outside the state all together instead of worrying how much renewable energy we have as part of the system. We could be producing that energy within the state at a far cheaper rate, saving taxpayers and utility users billions that can be used to spur the economy.

Meanwhile, we can create low interest loans to support energy efficiency improvements in older infrastructure including older building renovations. These loans can be financed by the cost savings from the higher efficiency of the building itself. It’s already been done.

AG – as you likely know, in-state energy production from large wind turbine sources was considered a very positive outcome. That was one of the original intents of having a renewable mandate for the State of Wisconsin. Since every kilowatt produced from wind, was one kilowatt that was not purchased out of state from coal or natural gas produced. Farmers that lease their land for large wind turbines also realize an annual income of around $4,000 per turbine.

Wisconsin’s governor also messed up on interurban transit improvements, the manufacture of the trains, further expansion of wind turbine tower manufacture and maintenance in Milwaukee.

Wisconsin lost 2 major car manufacture plants and at least 3 paper mills from the economic downturn. This resulting in the permanent loss of thousands of jobs, and many supporting businesses that aided in maintaining these large facilities. Retail job replacements are not an equivalent replacement.

One of the things I rarely hear discussed today is the ratio of 1/3 production type jobs that has always been considered the sweet spot to balance out the 2/3 of the service sector positions. Walker also robbed 15% of public worker wages directly taking money from local communities that help support and start small businesses. Walker further stole over a $1B from education around the state and these funds were shoveled off to his large donor base in the form of tax breaks and direct payouts without any accountability or job creation in his WEDC scam. All of these actions have been a detriment to any positive pull for the job stimulation side.

We have the least educated governor and legislature in modern history that lacks basic understanding and experience and obtaining models from ALEC that have no proof of working is not the answer. It has led WI on a downward spiral and trap that will be difficult to pull out of.

Maybe Bruce Thompson can do a comparison on MN and WI.

We could use some motivated politicians who are dedicated to make this state more entrepreneurial. Money from the great-grand-children of long dead late 19th and early 20th century entrepreneurs, and capital derived from large insurance companies … will not cut it in the 21st century. Our state is imploding and needs to change. I have started companies and worked with venture capitalist in California – I may not be rich and successful but I can certainly be a more credible advocate for a entrepreneurial Wisconsin than my legislative opponent.