The Rise in Income Inequality

The problem is national, but choices made by Walker and the Republicans may widen or reduce it in Wisconsin

When I was a kid in the 1950s the American myth was that we were a middle class country and growing more so, on our way to abolishing poverty. A look at the numbers shows that there was a basis for this idea.

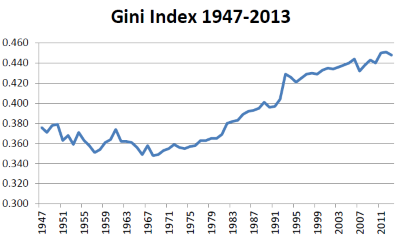

The chart on the right shows the “Gini” index since World War II. The Gini measures income inequality. The lower it is, the more evenly incomes are distributed. After falling in the first few decades after the war—reflecting broad-based postwar prosperity–the Gini reversed course as incomes grew faster for people at the top than the bottom.

Until recently, concern about rising inequality was often dismissed as envy. It was argued that a rising tide lifts all boats or that inequality supplied dynamism to the economy.

Recently, however, it’s become clear the rising tide has left most boats behind. The current economy has uncomfortable echoes of the Gilded Age at the start of the 20th Century, when a few enjoyed unprecedented wealth at the expense of most people, leading to Teddy Roosevelt’s attack on “malefactors of great wealth.” The argument that inequality is the price of “opportunity,” the ability to go from rags to riches, fails when international comparisons are made. PolitiFact recently concluded that the U.S. is the least socially and economically mobile country in the developed world.

The causes behind these trends are poorly understood and controversial. Technology certainly plays a role, making it possible to increase output while cutting the number of workers. Silicon Valley companies with a handful of employees are being sold for billions of dollars. Globalization is another culprit. Jobs, particularly in manufacturing, are moved around the world in search of lower costs.

In the U.S. the growing imbalance between executive compensation and that of workers contributes to the problem. In part this stems from efforts to design compensation formulas that align executive incentives with the interests of shareholders. This is an example both of good intentions gone awry and an indictment of executives’ character, implying that they need incentives to do the right thing.

Concern about income inequality has spread to some business-oriented organizations. For instance, Standard & Poor’s recently issued a report entitled, “How increasing income inequality is dampening U.S. economic growth, and possible ways to change the tide.”

Even some Republicans have caught on to the concern about growing inequality. In a recent article in Slate, William Saletan reports many examples of Republicans running against inequality in the recent election: supporting raising the minimum wage, expanding the earned income tax credit, denouncing regressive taxes that “harmed the poor and working families more than anyone else,” pointing to high rates of poverty particularly among minorities, lamenting that “median household income has declined in this state,” and and lamenting that the economic advantage has shifted so strongly from labor to capital. Jeb Bush actually sent out a fundraising letter saying that “among the developed nations, we are the least economically and socially mobile country in the world.” There’s a growing recognition that most Americans are on the losing end of the inequality game.

It may be argued that in the long run, these trends will be self-correcting. Growing prosperity in China and other developing countries will lead to growing markets. New jobs will be created by new technology. To some extent, these trends can be seen as continuing a process that started with the invention of the printing press, making it possible to produce books without employing teams of scribes.

But French economist Thomas Piketty, in his surprising best seller, Capital in the Twenty-First Century, argues against these rosy scenarios. He concludes there are no natural forces pushing against the steady concentration of wealth, that only a burst of rapid growth or government intervention can keep economies from returning to the imbalance of Teddy Roosevelt’s time. Piketty recommends a global wealth tax to prevent soaring inequality contributing to future economic and political instability.

Meanwhile, there is anything but a consensus on the need for government policy to counter growing inequality both nationally and in Wisconsin. In fact, there is strong support behind measures that would increase inequality and opposition to measures that would reduce it.

Taxes are an example. The Tax Foundation in its ranking that puts Wisconsin among the ten worst states downgrades states with inheritance and estate taxes and those with progressive income taxes. Similarly the American Legislative Exchange Council, or ALEC, rates states higher if they have flat income taxes or no income taxes and don’t have a minimum wage. Such organizations promote their agenda not as a way to increase inequality, but as a way to increase jobs, despite the lack of clear evidence one way or the other.

Those wishing to attack growing inequality have several political challenges. Any proposal to reduce inequality will be attacked as a job-killer. In some cases there may be validity to these arguments. In others, the arguments will be based on very selective use of data.

Those wishing to reduce inequality should recognize that good intentions are not enough. Well-meaning efforts can have unintended consequences. One example are the court-required school integration plans in Milwaukee and other cities that resulted in white flight and racial segregation that largely followed city boundaries.

Proposals to achieve equity can also lend inadvertent support to the divide and conquer strategies opponents of reform will use—the claim that a proposal only benefits a particular group such as a minority.

Decisions in Wisconsin in the next four years will present challenges and opportunities for those concerned about inequality and the hollowing out of the middle class. For example, will the budget changes made to fill the $2.5 billion gap between budgeted and proposed expenditures in the next three fiscal years and projected revenue help make the gap bigger or smaller?

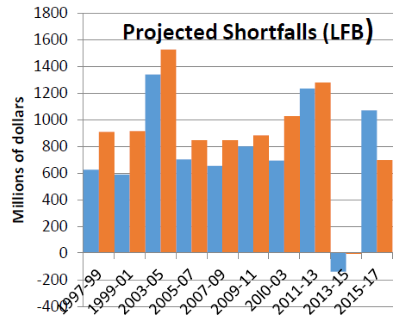

In a September memorandum, the state Legislative Fiscal Bureau recalculated the projected shortfalls for the 2016 and 2017 fiscal years. Because of lower than projected tax revenue it radically increased the estimate of the funds needed for a balanced budget. The total gap for the two-year budget grew from $642 million it estimated in May to the September estimate of $1.76 billion.

As can be seen from the chart on the right, this returns the projected shortfall to the levels typical over the past twenty years. This gap (sometimes called the “structural deficit”) does not mean the budget will be unbalanced—something the state constitution prohibits. Rather, it measures the challenge the governor and legislature will face in creating a balanced budget.

It is notable that the only 2-year period when the budget did not start with a gap over one billion dollars is the most recent one. That is the budget that benefited from Act 10 and the shifting of public employee benefit costs from the state and local governments to the employees, something unlikely to be repeated in the future.

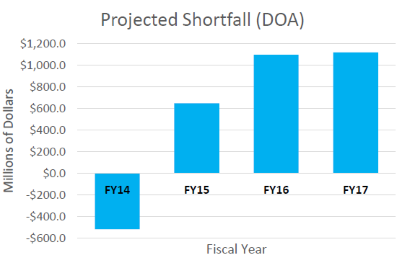

A November 20 budget report from the Wisconsin Department of Administration (DOA) reflects similar challenges in creating a balanced budget. As can be seen in the next chart, the budget for the current fiscal year (FY 15), originally designed to be balanced, is projected to run a deficit, which will have to closed by increasing revenues or cutting or delaying expenditures. For the coming 2-year budget, the gap between requests from agencies and projected revenues has returned to levels exceeding a billion dollars.

Balancing the budget will be made more challenging by Governor Walker’s commitments in his re-election campaign to further reduce income and property taxes, and to protect the elimination of most taxes on manufacturing and agriculture. It is likely that cuts already made are a factor behind the current budget moving from balanced to the red. The revenue estimates coming from the Walker administration are “based on existing tax law and are the result of economic activity, not proposed general tax law changes.” The changes proposed by Walker could only make the challenge bigger.

In its budget projections, the Walker administration doesn’t acknowledge the role tax cuts likely played in creating the gaps. Instead, it blames the so-called “fiscal cliff,” when the Bush tax cuts were scheduled to expire. The theory behind this argument is that tax revenues were higher in fiscal year 2014, as people sold assets to lock in lower capital gains rates and avoid a surcharge on investment income, and therefore lower in the current year.

How the legislature and governor address these gaps will go a long way to determining whether Wisconsin increases the growing economic inequality or acts to counteract it.

Data Wonk

-

Why Absentee Ballot Drop Boxes Are Now Legal

Jul 17th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

Jul 17th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

-

The Imperial Legislature Is Shot Down

Jul 10th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

Jul 10th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

-

Counting the Lies By Trump

Jul 3rd, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

Jul 3rd, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

It’s ironic that this is posted on the day after the Wisconsin Manufacturers and Commerce head announced that making Wisconsin a “right to work” state is so vital to Wisconsin’s future economic success. Along with that, he asserted that the top income tax bracket should be done away with and that the gas tax and the vehicle registration fees should be increased.

The rich just assert that they need more breaks to make them richer and that those who aren’t in that catagory should make up the difference.