Who Let the Dogs Out?

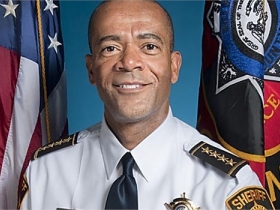

Sheriff Clarke grabs canine units from House of Correction, endangering safety of staff, only to be forced to return them.

Sheriff David Clarke has evicted tenants who treated their homes with more respect than he showed the House of Corrections when he lost his lease there.

In his reluctance to relinquish control of the facility to new superintendent Michael Hafemann, Clarke did everything he could to make the transition miserable.

It has been reported that Clarke threatened to arrest Hafemann for refusing to accept a number of inmates that the sheriff wanted to dump on Hafemann.

Hafemann protested the move, saying his facility was not prepared for the inmates at the time, in part because Clarke, when he had control of the place, refused to make necessary accommodations available.

It has not been reported that Clarke also severely jeopardized the safety of inmates and staff at the House of Corrections when he took the facility’s canine units with him, transferring them to the jail.

“The sheriff moved the dogs downtown,” said County Executive Chris Abele. “I can hear them barking” in the courthouse, he added. [Canine teams live with their handlers.]

House of Corrections Superintendent Michael Hafemann confirmed the transfer. “The sheriff moved all canine teams to the jail,” he said. But they’re coming back.

“Fortunately, we were able to get teams in place,” he added. “We have seven teams now, and three more will come soon.”

The Milwaukee County Sheriff’s Department operates the largest canine unit in the state of Wisconsin, with about 12 of its 20 teams assigned to the House of Correction, according to a 2011 document, issued when Clarke still had control of the facility.

In the article in “The Office,” the in-house magazine of the sheriff’s department, Clarke left the reader shuddering at the thought of a House of Corrections bereft of a canine unit.

Well if the dogs were so bloody important when Clarke ran the House of Correction, and so vital to the well-being of its staff, the reasonable reader must wonder why he insisted on taking the units with him when he lost control (to coin a phrase).

The only answer can be that vigilante Clarke has very little respect for The Law that he so assuredly claims to profess to honor.

He put staff and inmates at risk, that is clear. And I wonder about the dogs as well.

Fun Fact:

There is a David A. Clarke School of Law at the University of the District of Columbia.

Oh dear irony, of course it is not named after our David A. Clarke, Jr., but after a former District of Columbia lawyer and council president.

He was eulogized at his death at 53 in 1997 with these words:

No one, before or since, has ever bridged the racial divide in Washington with as much confidence and hope as did Dave. He genuinely cared for the poor and the powerless, and dedicated his life in service to this community.

No doubt about it, that’s a very different David A. Clarke than the one we’re stuck with.

Harley-Davidson 110th Wrap-Up

The Harley-Davidson 110th anniversary party celebrations in Milwaukee have come and gone. Which Urban Milwaukee neighborhood was the most popular for the visitors? I’d say Brady Street takes the honors based on my personal observations and those of others.

“I think Brady Street is the best venue,” a woman on the street said Saturday evening when the 9-block street running from the lake to the river was parked full of motorcycles.

“I’ve heard that a lot,” said Teri Regano, who was selling 16-ounce Pabst beers for $3 from a booth outside her historic Roman Coin tavern.

An official party on E. North Avenue did fair business, while in Walker’s Point, the traffic was “dismal,” in the words of Shaker’s owner Bob Weiss.

Indeed, compared to past years — before the improvements there — South 2nd St. seemed rather sedate, with only the occasional ear-splitting roar of the motorcycles. There were few banners welcoming riders and promoting Jack Daniels in the tavern windows, and there sure were many more rainbow-flagged Harleys outside the gay bars during past Harley Fests.

E. Chicago St. was a lively place leading to the Henry W. Maier Festival Park, but an art fair in the Third Ward closed off Broadway to vehicular traffic, which may have impaired the ability of some places there to do business with bikers and vice versa. Perhaps that was the idea.

Great Lakes Distillery, located within sight of the Iron Horse Hotel, and at the south end of the bridge leading to the Harley-Davidson Museum,was prepared for crowds that did not materialize.

Like the Walker’s Point neighborhood, perhaps it is located too close to the Ground Zero of the Harley Museum. What’s the use of jumping on a motorcycle and traveling just a few blocks before dismounting again?

But a trip to Brady Street — just the right distance from the museum and the festival grounds.

Steph Salvia, the executive director of the Brady Street BID said the experience “was awesome… I am exhausted. I keep hearing from others that Brady St was THE place to be. No issues reported from MPD outside of a couple of local drunks. (The usual).”

It is worth noting that Brady Street has hosted Harley parties for all of the company’s anniversaries, and has the party infrastructure down. Other neighborhoods (those that chose to do so) also staged their parties professionally and as effectively as possible, considering the fickleness of crowds. This in some measure must be due to the various BID boards, which among other things, have helped communities develop institutional memories on how to host a gig for tens of thousands of people.

In the past, neighborhoods like Brady Street might organize a street party, but very often the committee would then disband. Even more often, the committee and its volunteers may have suffered from disorganization, competing internal priorities, a lack of control over the event, and uncertain financing.

Those days seem to be behind us here. Brady Street, for example, downplayed the security aspect of the festival, largely relying on the omnipresent Milwaukee Police Department patrol officers and the remote cameras they hauled onto the street for the event.

The Brady Street BID also hired an 8-person cleaning crew to work during the event keeping things orderly. (Nothing promotes disorderly conduct quite like disorderly surroundings.)

Whether Harley-Davidson and Milwaukee World Festivals had a successful outing remains to be seen. There is some anecdotal evidence that business was down there.

Michael Glorioso, of Glorioso’s Italian Market, said he went to see the Doobie Brothers on Friday night.

“They had all the beer tents set up over the grounds, with 8 bartenders in each booth, and maybe two customers.

“But there were lots of grey-hairs drinking bottled water, and eating ice cream bars.

“Imagine that. Bottled water and ice cream bars! There goes a bunch of stereotypes.”

Photos from the 110th

Wheel Fever

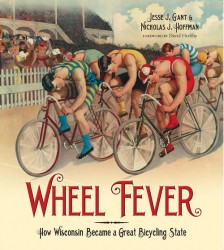

A little over two years ago I was contacted by a young historian who wanted to talk about some articles I had written about Milwaukee’s bicycle history that he had come upon while researching a book he planned to write with a co-author. I was happy to share my meager resources, and even more happy to have an insight into the demanding world of academic publishing as practiced by the Wisconsin Historical Society Press, publishers since 1855.

Now, two years later, Nicholas J. Hoffman and Jesse J. Gant have released “Wheel Fever: How Wisconsin Became a Great Bicycling State.” [One of my stories is included in source notes, and I received an acknowledgement in the book for my “encouragement and support,” along with other individuals.]

“Our original intent was to publish a complete history from 1869 to the present, but the characters and stories from the first boom proved too rich and we ended the narrative around 1900,” Hoffman wrote in a cover letter accompanying a review copy of the book.

“As you know, bicycles have barely received a footnote in state histories, but hopefully the state’s growing interest in all things bicycle will encourage more studies.”

Wheel Fever is certainly a good first step. Hoffman is the chief curator at the History Museum at the Castle in Appleton, while Gant is a Ph.D. candidate at UW-Madison.

The authors look at early Wisconsin bicycling history while paying close attention to race, class and sexual identity issues prevalent at the time. Early elite cyclists expressed their disdain and sometimes contempt for their peers — and implicitly for their inferiors as well, which they readily found in women, blacks and people of lower economic status.

Fortunately the authors provide enough source documentation to keep this thesis from being a buzzkill, revealing a great deal about the white-male-dominated society of the late 19th century and the remarkable machine that it embraced — and then dumped.

Among the book’s many surprises is the now-forgotten publications that documented many of these issues contemporaneously. The state’s African-American press (who knew that Lacrosse had a black newspaper?) wrote knowledgeably and tellingly about the white race’s attempts to dismount black riders from their clubs and competitions. Contrariwise, the mainstream white press covered bicycle developments condescendingly, especially when they mentioned women bicyclists or non-whites.

The book is well-illustrated with archival and contemporary photographs. Milwaukee gets its due, of course, as the largest city in the state, but the authors also present a case that “Wheel Fever” gripped the whole state, and that the bicyclists of late 19th century Wisconsin were the first to promote and lobby for “good roads.”

As it was then, so is it now, the authors conclude. As the last sentence of the book reads, “You might not think it, but your next bike ride is very much a political act.”

The authors are making the rounds of the state promoting their book and will make two appearances in Milwaukee in the upcoming weeks.

They will be at the Milwaukee County Historical Society Saturday, September 28th at 10 a.m. for a book talk, followed by an optional 11 a.m. bike ride of historic downtown Milwaukee bike sites.

The authors will return to Milwaukee Wednesday, October 9th, at 7 p.m. at the Chudnow Museum of Yesteryear, 839 N. 11th St. Admission is $2 for children, and $3 for adults. There will be antique bicycles on display in addition to bike riders on old machines.

Plenty of Horne

-

Milwaukee Modernism Gains National Awards

Dec 15th, 2025 by Michael Horne

Dec 15th, 2025 by Michael Horne

-

New Rainbow Crosswalks Mark Milwaukee’s LGBTQ+ History

Oct 8th, 2025 by Michael Horne

Oct 8th, 2025 by Michael Horne

-

Welcome Back, Tripoli Country Club!

May 27th, 2025 by Michael Horne

May 27th, 2025 by Michael Horne

Why would it be a surprise that Sheriff Clarke is trying to hold on to some of the few resources he has? The facility has been run far better since it was taken over by the Sheriff’s dept, the county never should have taken it away in the first place. The politics between the county board and Sheriff Clarke is getting really old and it’s only hurting the county in the long run.

Out of curiosity, if there’s 12 teams available for the correctional facilities… why do 10 go to Franklin and only two left downtown?

“The Milwaukee County Sheriff’s Department operates the largest canine unit in the state of Wisconsin, with about 12 of its 20 teams assigned to the House of Correction, according to a 2011 document, issued when Clarke still had control of the facility.”

“We have seven teams now, and three more will come soon.”

Even if they weren’t split evenly, why should they be?

Maybe there are more inmates in Franklin?