New City Law Fails to Help Black Contractors

2012 ordinance aimed to give more access but only 1 of 125 contracts went to black-owned businesses.

Minority subcontractors are vying to win city construction contracts under Chapter 370. (Photo by Sue Vliet)

In January 2012, a new ordinance went into effect that African-American contractors hoped would give them access to more city business. However, after a year of implementation, the race-based requirements have done little to help black-owned construction companies get a foot in the door, and the program has been suspended indefinitely while the city evaluates its effectiveness.

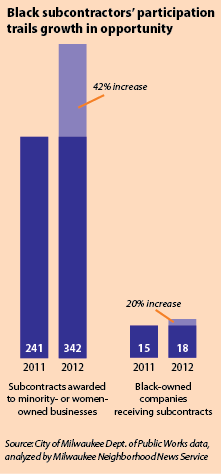

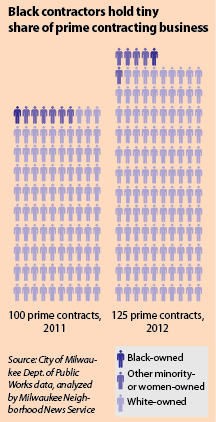

Public records provided by the Department of Public Works and analyzed by the Milwaukee Neighborhood News Service indicate that only one black-owned construction firm (Platt Construction) served as a prime contractor in 2012 when the city awarded 125 prime contracts. One black-owned firm (Adkins Family Enterprises) served as a prime contractor in 2011, when the city operated under race-neutral participation goals. The city awarded 100 prime contracts that year (see graphic, “Black contractors hold tiny share of prime contracting business”).

Some of these firms were hired multiple times to meet the requirements of the 2012 ordinance, known as Chapter 370. In 2012, the 18 firms received 124 subcontracts.

“We know the law was well intended, but we haven’t seen marketable increases in contracting opportunities for African Americans,” said George Lawrence, executive director of the Wisconsin Chapter of the National Association of Minority Contractors (NAMC). There are 187 certified black-owned minority business enterprises in Wisconsin.

George Lawrence is executive director of the Wisconsin Chapter of the National Association of Minority Contractors. (Photo by Sue Vliet)

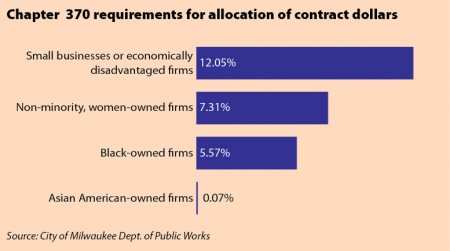

The ordinance known as Chapter 370 required the city to allocate 5.57 percent of annual construction dollars to certified black-owned firms. The law also required that .07 percent of annual construction dollars go to Asian American-owned firms, 7.31 percent to non-minority women-owned firms and 12.05 to small business enterprises or firms with an economic disadvantage (see graphic, “Chapter 370 requirements for allocation of contract dollars).

Prior to 2012, a race-neutral Emerging Business Enterprise (EBE) program required the city’s contracting departments to spend 18 percent of total dollars with EBEs on prime or subcontracts. For EBE certification, a small business needed to be owned, operated and controlled by one or more disadvantaged individuals.

Complaints pending

On May 1, 2011, the Hispanic Chamber of Commerce of Wisconsin filed suit against the city challenging the ordinance.

The Hispanic business group claimed that Chapter 370 provides race-based preferences in city contracts to some Minority Business Enterprises (MBEs) but not others, such as Hispanic-owned businesses. Firms qualify as MBEs if they are 51 percent owned, operated and controlled by one or more African Americans or members of another minority group.

The lawsuit asserts that a 2010 disparity study on which the ordinance was based was methodologically flawed. It also claims that Chapter 370 does not require businesses to certify that they have suffered from discrimination or are now socially or economically disadvantaged.

The study, conducted by a Florida-based consulting firm, showed there were more black-owned firms qualified, available and willing to work on city projects than were utilized. It showed no underutilization of Hispanic firms.

In June 2012, the NAACP filed a complaint with the U.S. Department of Justice against the city for discriminating on the basis of race and national origin in contracting and procurement.

According to the complaint, “disparities in the value of contracts and subcontracts with the city of Milwaukee to minority-owned businesses persist despite studies by the city documenting those disparities and identifying in recommendations steps the city should take to reduce or eliminate them.”

According to the complaint, “disparities in the value of contracts and subcontracts with the city of Milwaukee to minority-owned businesses persist despite studies by the city documenting those disparities and identifying in recommendations steps the city should take to reduce or eliminate them.”

The NAACP complaint also charges that the new ordinance “makes no significant changes in the operation of the programs nor in enforcement of program requirements. …Furthermore, a court challenge to this new ordinance jeopardizes the continuation of the whole program without providing for equality of contracting opportunity and compliance with federal civil rights laws and regulations.”

Minorities have historically been under-represented in the construction field, noted Mark Federle, professor and McShane Chair of construction engineering and management in the College of Engineering at Marquette University. He added that city construction projects should reflect the city they are in—in terms of the demographics of workers—because they are the ones paying the tax dollars.

Assistant City Attorney Margaret Daun declined to comment on whether the city achieved its contracting goals because of the pending lawsuit.

The Office of Small Business Development provides a list of certified businesses that prime contractors can choose from to meet the subcontracting requirements, said Dan Thomas, personnel and compliance manager for DPW. Prime contractors are left on their own to subcontract with businesses with which they already have working relationships, Thomas added.

“If I’m comfortable working with a firm and he meets the MBE requirements for me I tend to use him again. I don’t go shopping to spread the wealth around,” said Jim Snorek, owner of Snorek Construction Inc., the prime contractor for 13 paving projects in 2012.

This reality has prompted African-American contractors to seek work elsewhere. “We go outside of Milwaukee and Wisconsin to get our line of credit and work because a lot of the inner city continues to want to work with the same contractors, so it’s hard to get our foot inside the door,” said Trais Haire, the African-American co-owner of Midwestern Roofing & Construction, Inc.

City contracts make up about 40 to 50 percent of the business at the black-owned firms interviewed by NNS. Many said they are trying to build capacity in the private contracting sector, where requirements are less stringent.

In Limbo

In February, the city suspended Chapter 370 for an undisclosed amount of time to assess its effectiveness, according to Daun, the assistant city attorney. Daun said the review is not yet complete and she does not know when it will be.

It is very common to reevaluate a new ordinance after a year or two and to make changes to it, said Dan Thompson, executive director of the League of Wisconsin Municipalities.

However, Thompson said that he has never heard of an ordinance being suspended during the evaluation process, but that does not mean it has never occurred on the local or state level. Thompson has been with the League since 1989.

However, Thompson said that he has never heard of an ordinance being suspended during the evaluation process, but that does not mean it has never occurred on the local or state level. Thompson has been with the League since 1989.

Chris Jaekels, an attorney at Davis & Kuelthau who represents several municipalities, said suspending an ordinance for various reasons is not unusual, but it can only be done for the length of time needed to study the issue.

“You can’t suspend (an ordinance) and then not diligently pursue figuring out what the problem is,” Jaekels said. He added that as long as the city is complying with state and federal mandates, it is able to suspend, modify or repeal the ordinance.

The Florida-based consulting group that prepared the disparity study for the City of Milwaukee in 2010 declined to comment on Chapter 370’s evaluation process due to the pending lawsuit. A spokesperson affirmed that the company is not conducting the review.

Aldermen who supported Chapter 370, including Ashanti Hamilton, 1st District; Joe Davis Sr., 2nd District and Willie Wade, 7th District, did not respond to calls and emails from the Neighborhood News Service.

“What I’m concerned about now is that there will be no MBE component—no breakdown of what you should have on a contract. We may not get anything,” said Stephanie Findley, founder and chief executive officer of Midwest Construction & Management Services, LLC, an African-American owned firm.

Her company served as a subcontractor on contracts with Concrete & Masonry Restoration, LLC, and SPS Infrastructure, Inc. in 2012. “We just hope we left a footprint in the minds of the general contracts to be hired for future opportunities,” Findley said.

A board member of the African American Chamber of Commerce of Greater Milwaukee, Findley supports Chapter 370 because she thinks it could benefit the black community by reducing the high unemployment rate.

Capital constraints

Black firm owners interviewed by NNS said the law gave their businesses an equal opportunity to bid on projects—but mostly as subcontractors. Construction’s competitive nature puts them at a disadvantage to bid as prime contractors, they said.

Government organizations are obligated to award contracts to the lowest qualified bidder, Thomas explained. Previous history with an entity and how a firm intends to meet contractual obligations also are considered.

Because many MBEs are still building lines of credit, it can be difficult for them to submit a bid that rivals their competitors.

“Capital is the problem with building momentum,” said James Phelps, president of JCP Construction, a black-owned MBE commercial and large residential property construction firm. “You may have the capacity to do larger projects but you’re constrained by what capital you have.”

Black firm owners also argue that city contracts don’t come close to reflecting Milwaukee’s population. Phelps said if you were to look at the certified payroll for a job site, the majority would have 262, 920 or 608 telephone area codes—meaning they are not from Milwaukee County.

Findley added that well-established companies based outside of Milwaukee can severely underbid local contractors to acquire city projects. “It leaves a bad taste in your mouth,” she said.

Another barrier keeping black-owned MBEs from bidding on and winning public projects as prime contractors is their inability to afford what are called bid and performance bonds.

These monetary down payments are required up front from the firm that is awarded the public contract as the lowest bidder. They secure the firm’s promise to complete the project under the contract’s terms and conditions.

“There are a lot of black-owned firms but a lot don’t have the capacity to (afford) a bond,” said Michael Peratt, corporate secretary at Platt Construction—the only certified black-owned MBE to serve as a prime contractor in 2012.

“It’s going to take a while for some of the minority firms to develop enough bonding power to get jobs as a prime,” Peratt added.

Haire, of Midwestern Roofing & Construction, Inc., said his firm was dropped by its insurance company in 2008 with the downturn of the economy and it has been hard to afford a performance or bid bond ever since.

Black firm owners agreed that prime contractors tend to hire subcontractors who look like them. “These people have had relationships that have been in place for many years—generations,” said Joe Dahl, chief operating officer of Milwaukee Metro Management, a black-owned company that specializes in property management and remodeling services.

Dahl said the procurement process is “relatively fair” but it is important to hire African-American owned firms because the investment will make its way back into the community and hopefully lessen unemployment.

“I do believe that people need to be competitive and provide quality work,” Dahl added, “but the race didn’t start off where we were both at the starting line.”

This story was originally published by Milwaukee Neighborhood News Service, where you can find other stories reporting on fifteen city neighborhoods in Milwaukee.

Political Contributions Tracker

Displaying political contributions between people mentioned in this story. Learn more.

- December 13, 2017 - Ashanti Hamilton received $340 from James Phelps

- January 13, 2016 - Ashanti Hamilton received $67 from James Phelps

If you go to urbanmilwaukee.com and click on City People, you’ll see a profile about black contractor, James Phelps.

I thought Platt was American Indian, not Black